Reviews

Aurevelateur

published on Cyclic Defrost November 25th, Sydney © 2005

by Bob Baker Fish

Melbournian Philip Brophy has been obsessed with film sound and music for years. He has created it, written about it, taught it and even organised an annual conference that celebrated the often ignored or misunderstood art form. The concept behind his latest work is intriguing to say the least. A commission from the Melbourne Film Festival in 2004 it is part of an ongoing series of composing scores to existing films. Though this is where it gets interesting. Rather than getting in line behind the Cinematic Orchestra and Michael Nyman and hacking out another score to a the Man With The Movie Camera he’s opted for the little known 1968 French film Le Revelateur. And rather than throwing a few synth based washes of electronics around he’s taken a different approach. And I’ll use his words: “I see my score as a dialogue with the film – something that proposes a ‘cover version’ of the movie rather than any definitive enhancement of the original.” So how do you have a dialogue with Aurevelateur? Indie pop judging from the opener Diamond Sun, which features vocals from Sianna Lee (Love Outside Andromeda) and Brophy himself. Actual songs in a melodic kind’ve catchy French provincial way. Also featuring Dave Brown (Candlesuffer/ Bucketrider) on bass and guitar with Brophy handling keyboards and drums, the score moves into more traditionally filmic minimal areas, though also rocks out in a very satisfying 70’s Krautrock way as Brophy weaves an interesting trajectory throughout not only the course of this album, but the course of individual songs. My Stars Tell Me for example is a piece defined by mannered stasis which just erupts in a frenzy of guitar midway. Then inexplicably there are two covers of Bowie’s Heroes, the second and final version on the album is particularly satisfying, a slightly baroque low-key effort with treated whispered vocals over a strange waltz. And it all stands up independent, of the contextual support of the film – which is quite lucky given that few of us are likely to come into contact with Le Revelateur anytime soon.

Aurevelateur

published in Real Time - Ear Bash May 1st, Sydney © 2006

by Jonathan Marshall

Philip Brophy has made a manifold contribution to Australian screen/sound culture as a composer, curator, critic and teacher across media (installation, CD, live performance, journals, popular forums). His Sound Punch label has released 9 CDs by Brophy and others over the last 6 years. The latest is Aurévélateur which, like Beautiful Cyborg (see review) (2002), was originally devised for live performance as a score-in this case to director Philippe Garrel's bizarre filmic critique of the bourgeois family, Le révélateur (1968). Garrel's movie largely consists of the silent flight of a family through a mostly empty, darkened landscape; a fractured retreat in terror from an unseen threat. This scenario is intended to represent the tensions and paranoias of the capitalist family. Le révélateur's startling power comes from its opacity, from the weird hyper-investment of the images which is partly created by Garrel's deliberate use of silence rather than soundtrack. It is therefore hard to see what Brophy's music might add beyond a certain banality of theme, an emotional/musical consistency, or a sense of dated historicism—not least as Brophy's broadly unified score tends to sew together Garrel's deliberately disjointed scenography.

Like Beautiful Cyborg therefore, Aurévélateur is most satisfying if one ignores its filmic origins and considers it as a purely listening experience. At this level, Aurévélateur functions as probably the most poppy and accessible of the Sound Punch releases. With Dave Brown of Lazy and Candlesnuffer fame adding bass and guitar, and Sianna Lee vocals, Brophy's keyboard and drums come together to produce something very much akin to the revival of late punk, 'kraut-rock' and post-punk electronica which has recently been produced by Ladytron, Chicks on Speed, Life Without Buildings, Rocket Science, Franz Ferdinand and indeed too many bands to name. Brophy's melange brings forth something more of late 1960s, early 70s psychedelia and head-music to the mix than most of these other re-interpreters (the vaguely Jefferson-Airplane-like neo-lounge of Broadcast aside). In the end though, there is little that one would not hear at a good night either at the Factory during a performance of the Exploding Plastic Inevitable, the Velvet Underground or Lou Reed, or perhaps during one of the later Koolaid Acid Tests with the Grateful Dead et al. This is fine, but it is not very remarkable. In addition Brophy tries to underline the theme of Le révélateur with 2 versions of David Bowie's epic Heroes. Part of what made this song work was the sense of desperation and vocal friction in Bowie's enunciation as he begins to cry out at the finale with a wonderful technique that takes him close to a scream. Brophy by contrast sings “I wish I could swim / like dolphins can swim” in an oh-so-cool, presumably ironical, postmodern, deadpan fashion, all but eviscerating Bowie's masterpiece.

Brophy has described his recording as not so much a new score but a “riff” on Garret's film. One must therefore ask what Brophy has added to the heritage, sounds, dynamics and images of late 60s, early 70s culture with his noodlings, and conclude not all that much. Heroes aside, this CD makes for a good listen, with dirty guitar and Moe-Tucker-style drumming interspersed with loungey organ. However I would advise those seeking to add to their collection to go through Sound Punch's fantastic back catalogue before considering this particular release.

What to make of Philip Brophy's music?

published on Just Outside January 21st, New York © 2010

by Brian Olewnick

(...) Sound Punch, the label devoted largely to the dispersal of Brophy's music, carries a design motif that actually reflects much of its product quite well: slick, eye [ear]-catching, blandly hip. Each release includes a slyly descriptive subtitle. "Au Revelateur", whose songs were written for a 1968 silent movie by Philippe Garrel (an amour of Nico), is so labeled, "softly rock-Euro foliage" which may be as good as any, as far as capsulized descriptions go. The pieces have a quasi prog-rock, 70s feel, with prominent organ and explosive, orgasmic guitar stylings. And dammit, it's catchy, soothing, succor-giving--all that awful stuff! I may have thought "Journey to White Light" was the most amazing thing I'd ever heard, had I heard it in 1969 at 15. As is, well, it's a helluva lot of fun, all glistening Rileyesque organ-chimes, sighed vocals, percolating along like nobody's business. Is it good? Of course not. But it's fun. Even the two covers of Bowie's "Heroes" one lush, one pared down, work effectively....wait, I'm feeling a sugar overdose coming on...Well, I couldn't in good conscious really recommend this to regular readers here, but what Brophy sets out to do, he does rather well, I must admit.

Articulating Silence

published in Real Time No.72, Sydney © 2006

by Robert Lort

Over 2 nights the Brisbane Powerhouse presented the live film music of Philip Brophy, the second night featuring a score for Philippe Garrel’s controversial silent film Le Révélateur (1968). Brophy’s background includes work as film director, sound designer, lecturer, film programmer and curator. He is probably best known for his visceral Cronenberg styled feature Body Melt (1993). The first night’s focus on Japanese animation, with vibrant colour and slick sound design attests to the stark contrasts in Brophy’s encompassing versatility. His multi-lateral approach to media is perhaps summed up in his statement, “I become [the media] in order to unbecome myself.”

The soundtrack grants us unimpeded access to the emotional interiority of film and thus easily assumes semantic dominance, hence the challenges confronting the score composer. In Dolby Digital 5.1 surround sound, Brophy commendably takes up the challenge of providing a score that goes beyond Brian Eno-esque clichés and the ever prevalent insert-Arvo-Pärt-here.

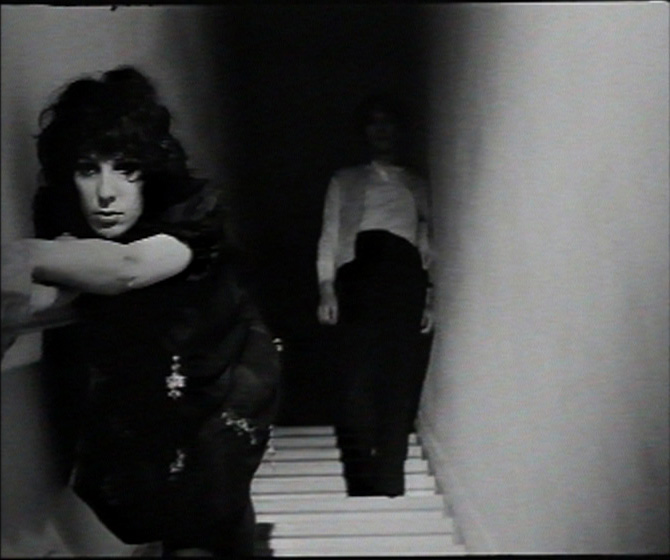

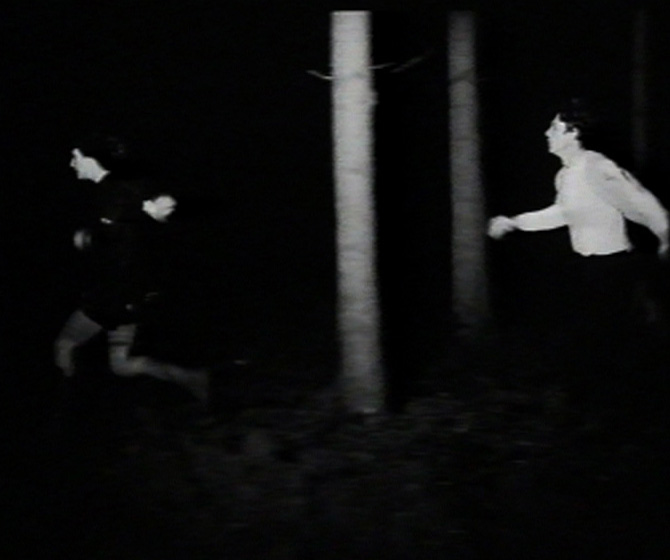

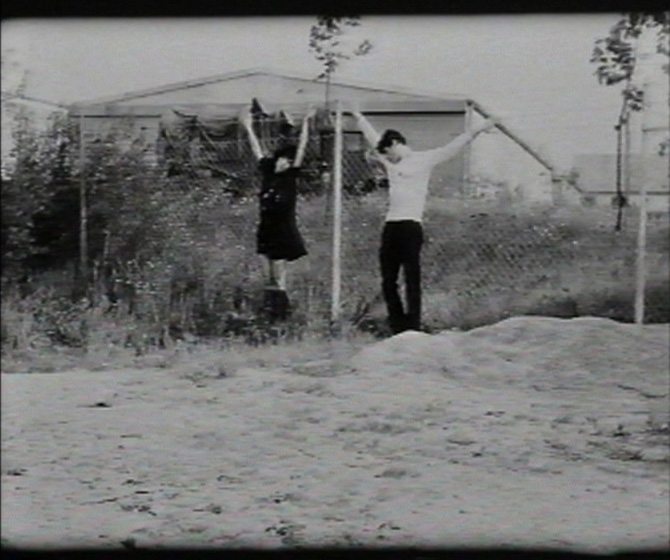

The rarely screened Le Révélateur is a hauntingly apocalyptic film composed in stark black and white contrasts of a man, woman and neglected child in psychological crisis. Reputedly the entire cast and crew took LSD before shooting; the eyes of the woman as she descends the staircase holding the rail with both hands makes this apparent. The characters, as though trapped in a box, avoid making any connection; like silent puppets they stare out at a bleak world. The now less tangible political context of the film was its birth in Garrel’s traumatic internalisation of the Paris riots of May ‘68, the resulting deflated ambitions and unrealised dreams and the consequent police crackdown and the dispersal of militants, propelling Garrel to Munich where he began filming.

In Brophy’s soundtrack the selection of music is historically decontextualised from the film’s 1968 origins; beginning with the violent and sinister eroticism of the Velvet Underground, it forward tracks through 70s German Krautrock to David Bowie and Joy Division. The harsh discordant guitar chords provided live by Dave Brown are thematically linked to Garrel’s 10 year romance with Nico (of the Velvet Underground). The savagery of menacing, pulsing, jagged edged sounds merges seamlessly with the stripped back and raw cinematic imagery. The cross-fading oscillation between over-exposed whites and an impenetrable darkness is recomposed in the auditory realm via the contrast of shrill explosions of electric guitar with the brooding darkness of the bass. A parallel dialogue between the gruesome aversions of the parents and the hopeful playfulness of the child is suggested in guitar versus keyboard. The protagonists’ persistent closeness to the ground—on their knees or hiding in the grass—is emphasised by scraping, rumbling and granular sound textures. In an additional original move, a female voice is added to the soundtrack coinciding with scenes where the woman turns to face the camera.

Brophy’s soundtrack emulates the stylistic structure of the film; the circular tracking shots of the camera correspond with the child tramping in circles, which correlate well with the repetition and looping of Krautrock. In one scene the child becomes a voyeur, watching his parents violently confront each other on a miniature theatre stage; the silence of the film is now embellished by wailing, distorted guitar. In the latter half of the film the child resolves his anguish, this is marked not only by his escape from the forest, but also his swapping the ever present doll for a can of fly spray. In Brophy’s soundtrack this development is signposted by the introduction of a cover version of David Bowie’s Heroes—perhaps forever embedded in the cinematic psyche with flight since its use in Christiane F as the ‘sound’ junkies flee from the police through the corridors of an emptied shopping mall. We can only wonder how Philippe Garrel would respond, but I sense this is the music he might have chosen.