Chapter I

Fabricating, Fuzzing & Forging

published in Stuffing No.2, Melbourne, 1989Enter Here

There are many ways we can play with the differences between `rock'n'roll' and `rock'. Interestingly, the core differences are contained within the linguistic, semantic and semiotic relations between the two terms : `rock' as a verb and as a noun. It's not as complicated as it sounds.

Rock'n'roll is historically sited in the fifties, at the birth of the music as a cultural form of communication and entertainment. The accent on the term `rock'n'roll' was on rhythm, on beat, and on the body's relation to the two. This terminological effect is an extension of other dance-music genre's like waltz and swing, where the term simultaneously describes the music's rhythmic form and its related dance. While this might seem obvious, it cannot be underestimated that rock'n'roll - especially to the parent culture of the fifties - was primarily viewed under these terms, as a phenomenon ultimately designed to induce the body into a state of rocking and rolling (hence the black voodoo associations). This is also why other rhythmic dance forms, styles and genres were being catalogued and marketed by the then-burgeoning youth-oriented recording industry throughout the latter half of the fifties and into the start of the sixties - calypso and twist being the two touted as most capable of replacing the `fad' of rock'n'roll. Worried parents saw rock'n'roll as a corrupting moral force because it liberated the pubescent body ; cunning A&R men saw it as having exploitative potential because of how it triggered the physical body. In short, the use function of `rock'n'roll' for everyone concerned was to consume by rocking and rolling.

If `rock'n'roll' was the action, `rock' is the act. This is not to say that rock is devoid of any of the features discussed above (the body and beat, etc.) but whereas rock'n'roll is the initial historical production of certain musical structures and social formations (all of which, as various `counter-histories' point out, were happening in an ad hoc, chaotic, multi-synchronous fashion across the States in the early fifties), rock is their extension, development and redevelopment. This of course is a cultural distinction, because musicologically rock'n'roll is simply another link in the political and morphological chains that spanned the Pacific in the 19th Century and the Atlantic and the States in the 20th Century. For our purposes, though, rock'n'roll is an important link in the socio-economic transformation of western popular music : just as the American postwar baby boom soon enough created a race of monstrous race of `teenagers' so too was rock'n'roll monstrously transformed. It became less an event and more a process; less something that grew and more something that was grown. Consequently, `rock' is viewed as carrying on a tradition, reviving things lost - which is another way of saying that `rock' has lost the fluid and fluidity which fueled `rock'n'roll' in all its truly experimental and intuitive phases. Rock'n'roll did things, moved things, leaving rock to be things, say things. That is the essential cultural difference displayed by the move from `rock' as verb to `rock' as noun; from doing it to being it.

But what is this fluidity I'm talking about? Is it what some people call the soul of music? Its roots? Its truth or essence? Not at all. In fact it's something a lot more tangible : sound. If rock'n'roll was a force, an energy that compelled and propelled people to move their bodies, change their attitudes and form their identities, then that energy is to found in the inarticulate, amorphorous, yet potent material presence of the music itself : its beat, its rhythm, its texture, its surface, its speed, its drive. These are among the prime components which animate, invigorate and energize, which give the music a sense of fluidity and movement. It is the sound of rock which gives the form its key image: those thrashing drums, that wailing guitar, that yelping, hooping scream, the overall sonic boom of a combo generating that energy we finally call rock'n'roll.

The unfortunate historical problem is that rock leaves us with a largely metaphorical/poetic/anthropological/social/philosophical/religious means to articulating the energy of rock'n'roll, when that energy is primarily sonic, aural, acoustic, electric, musical and rhythmic. Once everyone (especially rock critics - many still in existence today - who carried degrees in English Literature and/or dreamed of writing their own novels) started to explicate rock'n'roll they ended up mystifying it through a recourse to abstract concepts which at best hovered around the sonic event and aural effect of the music. This needn't be so. Take the opening two chords to Link Wray's Rumble. The effect and eventfullness of their sound is immense, but once you try to assign some `meaningful' meaning to them, you instantly jettison your listening placement into some other dimension light years away from the zone of the sound of those two chords - because you're not experiencing them. Their immediacy is replaced by your mediacy.

Rock'n'roll - and rock - is sound and is about sound. All sound is energy : one gets the impression it can be controlled, that it can control you and you can control it, but like most forms of energy its nature and status remain uncontrollable - only directable. Your sense of controlling it is effected by the power of the sound's own movement. Pick up a guitar and play those two opening chords to Rumble and you can thrill to the feel of that sound's power, but you are only a device, an interface, a medium, a means to an end. You and the guitar are both instruments, neither controlling the other, both interacting to produce the sound. That sound is an event of effects - temporal, technical, tangible. And they are the terms - its own terms - under which it is best addressed.

Fabricating The Ventures' Sound

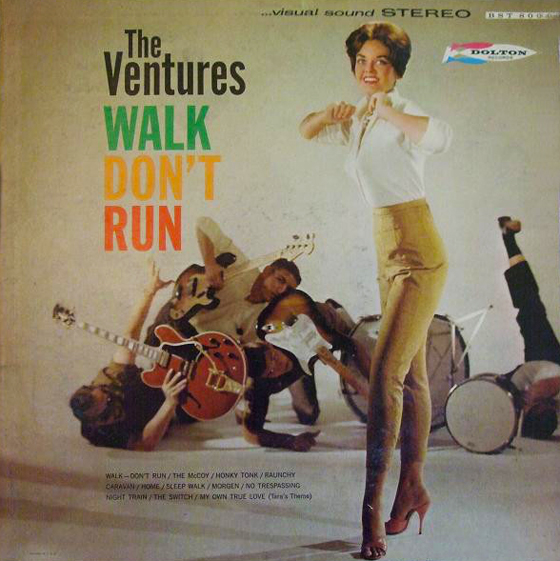

There's something weird about the original Dolton label cover to the Ventures' first album Walk Don't Run (1960). It features a 1960 version of a bright young secretary in tight pants and blouse and stiletto sandals, topped off by a Colgate smile and a tasteful bouffant. She's standing upfront, looking uncomfortable but nonetheless sexy and perky. Behind her is `the gag' : four band members with their instruments, all piled on top of each other, sprawled on the floor. She has obviously knocked them out, man. They're in the background - out of focus and wearing shades. For years, everyone presumed they were the Ventures, but in an interview in Guitar Player (September 1981) the Ventures revealed that they weren't even in the state when the album was designed, so Liberty simply got four guys from their stockroom to pose as the Ventures.

This is a very telling image of rock - of how rock makes images of itself. Not of how it imagines itself to be, but of how it `images' itself. An image from 1960 : the dawning of the fabrication of rock, of its marketing, its presentation, its manufacture. Two years before the Fab(ricated) Four, six years before the (pre-fabricated) Monkees. A time when American record companies were trying to sort out things from the detonations of the fifties' explosions of rockabilly and r'n'b, and project a new decade of potential development (mostly financially oriented) based on those rhythmic/seismographic vibrations from the fifties. But 1960 is no wondrous peak or momentous occasion. The history of rock and pop (as market and cultural forces) is forever in crisis over stasis, forever attempting to reflect, project and inject - anything to get some sort of payback. Between 1960 and 1963, The Ventures were the pay dirt, mined out of the settling dust of the previous four years of shakin' and rattlin' and knockin' and rockin', and exploitable until the British Invasion of 1964-65. That cover to their first album is a telling image of rock because the identity of a group was at that time a largely non-existent factor in the promotion of a record. The Ventures were presumed to be as non-specific as, say, The Comets without Bill Haley : a back-up combo (replaceable and interchangeable) without a primary focus on an individual with `the voice'. Music marketing at the start of the sixties was still generally caught up in tactics and schemes established by the movie industry and its focus on the solo star : the name, the face, the bio, etc.. While The Beatles are often acknowledged as being the first major success story in rock group-marketing, the Ventures' success is not to be overlooked, especially as they mark definite changes in the American music industry's conceptualization of how to present a group.

The Ventures are a genuine phenomenon because they didn't simply present a `new sound' - an alien and novel sonic `product' which triggered the ears and mind; they presented a manual for the production of a new sound. The early Ventures' records worked as incentives and programmes for any four kids to grab some instruments and knock out a simplistic instrumental number : you too can reproduce the sound of the Ventures. The song Walk Don't Run (rearranged into a rock format from jazz guitarist Johnny Smith's original composition) is archetypal in this respect. Listen to how clearly it separates drums, bass, rhythm guitar and lead guitar into a sequence of building blocks, as though it's actually demonstrating how to play the song. In a sense, the identity of the Ventures was fairly anonymous, in that anyone could utilize the `manual' suggested in their songs and thus become copies who could be just as good as the real thing.

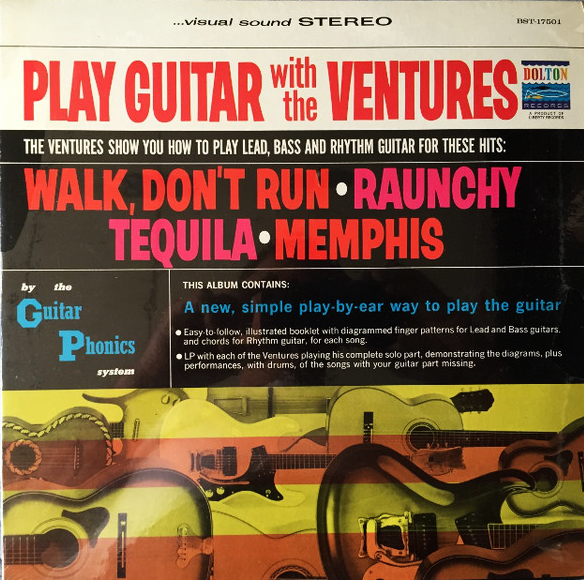

Once the phenomenon of the Ventures was rationalized, a certain logic settled in - a logic that culminated in the release of those three Play Guitar With The Ventures albums (1965-66). It was a logic totally based on how the sound of a rock combo could equate an image (a condition peculiar to instrumental music with its absence of a human vocal presence), and also how certain images could suggest and generate a sound. Those Play Guitar With The Ventures albums - complete with chord booklet and a teacher-like voice-over calling out the chords on the record - didn't sell the image of the Ventures as an identifiable product ; they sold the sound of The Ventures. Sound converted to image.

However, such a marketing strategy had its limitations. The Ventures released anywhere between three to six albums per year throughout the sixties - totalling forty-two albums in that decade alone. When you set their albums up in line you notice quite quickly the problems that must have faced them once their original identity of the streamlined, anonymous `sound-producing' combo faded. That uniquely anonymous first album (Walk Don't Run) couldn't be repeated mainly for two reasons : (a) its anonymity would eventually become its identity ; and (b) record marketing then (as now) required new product and image changes continually. Logistically, this can be restated as a two-pronged problem : (a) what songs should they cover? (remembering that The Ventures really weren't identifiable as song-writers) and (b) what trend or style should they push for that particular album (to keep up with market changes)? Out of this arose The Ventures' solution : (a) select a body of cover versions that could be thematically linked, and produce a matching body of original compositions that could be blurred with the cover versions, and (b) give that combined body of songs an image tag, an identifiable trait of contemporaneity (hipness). Thus you get (for example) Wild Things (1966) which features a cover version of The Troggs' original plus Ventures' originals like Fuzzy & Wild, Wild Child, Wild Trip, Wildcat and (wait for it) How Now Wild Cow. The album cover features three imitation `London birds' who are presumably a visualization of `wild things'. But most interestingly, the overall sound of the album is ... well, wild. A bit thrashy, a touch fuzzy, and with a noticeable `beat' flavour. Image converted to sound.

Virtually every Ventures' album from the sixties does this, sometimes obviously (The Ventures' Twist Party, The Ventures' Beach Party, Super Psychedelics, Swamp Rock, etc.) and sometimes obliquely (the raw `Cavern' sound of Where The Action Is which consciously competed with the British Invasion's raucous return to American r'n'b; the healthy-sporty-lifestyle feel of Runnin' Strong which picked up on the equation of youth and Californian sun; the Spotnicks/Tornados reverb effects on The Ventures In Outer Space which synched in with America's space age and shows like The Outer Limits; etc.). The reasons for this marketing strategy are also related to how The Ventures worked. All their albums were recorded and produced in very short periods of time, and often during tour dates, so that if a new album was needed while they were on tour they would apparently book into an available studio wherever they happened to be at the time. These factors would contribute to the evenness of sound texture and style of each album, plus the sonic differences between albums, as they were recorded in a variety of studios. So while the early Ventures' albums worked as manuals for aspiring instrumental guitar combos, the proliferation of later Ventures albums provided a series of identikits which demonstrated (a) how to convert image to sound, and (b) how to convert sound to image. The Ventures were possibly the first group to eventually realize this whole process, and to particularly realize that it could be adapted to suit changes in climates, markets and conditions (succeeding with these changes where others had failed : The Challengers, The T-Bones, etc.). They were a group whose image was generated by the production of multiple sound (styles, genres, categories, etc.); their sound by the production of multiple images (trends, fads, fashions, etc.).

Most importantly, such a way of working - and succeeding - seems to only have been possible because The Ventures stuck strictly to instrumental music : music devoid of the conventional presence of a human identity, an aural focal point with which the listener can identify. The Ventures (still going strong, and especially in Japan where Ventures copy-bands are rampant) in the end have retained their presence (market and musical) through a deliberated lack of identity, through presenting sound and image by absenting themselves. In effect, The Ventures are the first prime example of the incorporation of rock music : they effaced themselves in their very presentation by incorporating themselves into their music, displacing their identity into their sound. Think of their album covers : their logo was usually a more prominent feature than either a group photo or names of the personnel. Note, too, that when the cover of their first album was recreated for Walk Don't Run Vol.2 (1964) it didn't really matter that this time they actually appeared on the cover. As rock ideology developed throughout the sloganeering sixties, this effect of incorporation was seen to be an undesirable way of producing rock music - turning out soulless, automated, mainstream, empty sounds. While The Ventures were championed initially by fledgling guitar heroes, the counter-cultural wave which swept rock along in the latter sixties all but branded The Ventures approach as `rock-muzak' : a faceless twanging of banal tunes drained of any substantial energy. Nonetheless, as we shall discover, this notion of `muzak-rock' is integral to the development of the sound of rock - of rock as a sonic force and presence emptied of vocal identity.

I start with The Ventures for two reasons : (a) they are a key example of how image and sound - as concepts - dissolve into one another in rock music, and (b) this effect is clearly evident by 1963 - a quarter of a century ago, when the mechanics of the rock industry are being forged. The point is that by such an early stage, virtually all the major modes of the cultural production of sound and music had been realized : fabrication, appropriation, mutation, fragmentation, incorporation, commodification, etc. - modes which often are mistaken as being new and recent trends in the image manufacture of rock and pop music today. I also start with The Ventures so we can move on from them through a series of other groups, performers and producers who have largely been overlooked in most histories of rock music, yet are central figures in the development of the sound of rock.

Fuzzing Mike Curb With Davie Allan & The Arrows

`Muzak rock' is a term that fits a lot of work done by Mike Curb. But like The Ventures, his role was very important in changing ways in which rock imagery could and would be manufactured industrially, as well as in giving us a focus on rock as a stylistic sound (something to be mimicked) rather than a musical genre (something to be mastered). Mike Curb was a record producer in Hollywood who was largely responsible for the soundtracks to a whole slew of biker/JD/drug/rock films from the mid to late sixties. Most of his work was done for Tower Records (a division of Capitol Records who played both sides of the British Invasion, having The Beatles and The Beach Boys). Further to his work within Tower, Curb started up his own production company called Sidewalk Productions. This brief profile of Curb is important in demonstrating that his work was totally based on fusing sound with image for rock-styled soundtracks to rock-derived/oriented movie scenarios, because almost single-handedly he was responsible for creating the sound of soundtrack rock.

So what is `soundtrack rock'? I'm talking about that strange style of music which tries desperately to be wild, frenetic, raw and loud, but only ever sounds weak, timid, insipid and soft. All the right ingredients are there : fuzz guitar, wakka-wakka r'n'b chords, Farfisa organ wails, clucky-plucky bass, tinny snares and booming bass drum, etc.. But somehow it never connects or fuses, never punches out much power or presence. It will crop up on the soundtrack of a movie, and somewhere in the back of your mind is planted the idea that "it sounds like rock music". And that's the point : it sounds like rock music - but it isn't `the real thing'. It's only the sound of it. There's something inauthentic, unreal, wrong about it. You can smell the studio musos a mile away ; you can sense the overtly musical organization of the songs' structures and development.

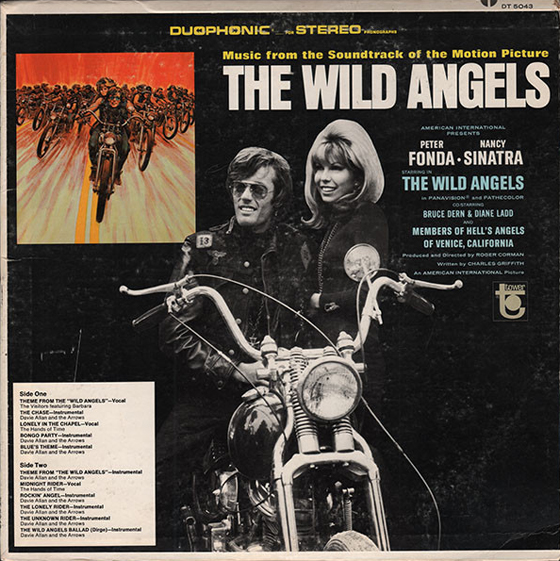

You can hear it on soundtrack albums like Wild Angels, The Born Losers, The Devil's Angels, The Glory Stompers, Teenage Rebellion, Riot On Sunset Strip, Thunder Alley, Mondo Hollywood, Wild In The Streets, Angel, Angel Down We Go, Wild Racers, Mary Jane, Wild Wheels, The Savage 7 and Psych-Out. These films date between 1966 and 1968 and all feature music composed and produced by Mike Curb (see Chart I for full details). Collectively, they are the definitive body of latter sixties' counter-culture exploitation movies, which form what I would tern the third major phase of soundtrack rock (the first being the the fifties' cycle of rock'n'roll movies; the second being the early sixties' cycle of pop movies encompassing the Elvis films and the Beach Party movies). The important consideration with this third phase of movies is that music is presented as part of a lifestyle - that is, something to identify with rather than consume. This is marked by the distinct absence of band cameos on screen, such as in the previous two phases which were basically wacky or tragi-comic stories peppered by isolated song performances by known stars. The subcultural exploitation movies use actual soundtrack music to provide an overall feel to the narrative, with the plot centering on situations in which the subcultural characters (druggies, bikers, hippies,delinquents, etc.) are snared, as if the music is the soundtrack to their `lifestyles'.

Ultimately, Curb's soundtrack rock is lifestyle music : a musical styling concocted to match a fictionalized scenario based on some sort of demographic sense of the audience watching the film. Straight forward exploitation. Curb replicated the sound of what he figured `the kids were into' (remembering that Curb was 20 when he did the score for Wild Angels in 1966). Sounds that obviously - sometimes like cue-cards - lent themselves to be directly associated with subcultural images, tokens and icons : hallucinogenic drugs, long hair, rumbling bikes, satanism, liberal sex, torn denim, leather boots, short skirts, etc.. Once again, we have a dissolving or fusing of sound and image as in The Ventures' use of imagery for their albums. And a lot of Curb's soundtracks sound not unlike some of The Ventures' `tougher' albums (The Horse, 1968, Underground Fire and Swamp Rock, both 1969) which lean toward San Francisco psychedelic and/or Stax-type soul. Both Curb and The Ventures were scoring soundtracks to mid/late sixties' lifestyles - not necessarily how they were at the subcultural level, but how they were imagined to exist at the popular level, especially in the minds of film, television and advertising executives (marking Curb a key figure of corporate rock, as opposed to The Ventures' incorporation; also, Curb later saw his corporate dreams through to becoming head of MGM Records and later a senator of California!). Curb's soundtracks are not the real thing, but an approximation, a semblance, a suggestion. The sound of rock.

But things are a bit more complex in the case of Mike Curb. Firstly, his soundtrack scores and songs might sound weak on record, but sometimes when they happen in the film (ie. with images) they can work very well. That is, their sound fits in well with the fictional world - believable or not - which the films construct. Sometimes, some of these films can punch in a bit of pounding drums and screeching fuzz guitar and give a scene power - a power which is hard to refigure or recapture when listening to the record. This of course is in the nature of soundtrack music, where you are always taking in the soundtrack with many other levels of information (acting, cinematography, script,direction, editing,etc.) so that the end effect of a particular scene is compounded : each level of information energizes every other level. The soundtrack can thus carry the power of other levels which it does not carry on the record. Secondly, some of the best moments of Mike Curb's scores can be directly attributed to one person : Davie Allan.

While Davie Allan might have been one of many other roving Hollywood session guitarists who moved through every possible plateau of the entertainment industry in Los Angeles, his work can be clearly traced through his collaborations with Mike Curb both on soundtrack recordings and on his own releases with his band The Arrows. The Arrows had what appears to have been a surprise hit (like The Ventures - in fact, like many instrumental bands in the early sixties when chart action was mainly regional in activity) in 1965 with their version of The Shadows' Apache which The Arrows titled Apache '65 (part of a fad that year for vamping up fifties instrumentals with a sixties flavour). The local success of the single led to the release of their first album on Tower - Apache '65 (1965) which contained a few standard covers with most songs written by Curb and Allan. (On the whole, this album is fairly tame, with the exception of their wailing cover of Andre Williams' Twine Time.)

The following year, Curb and Allan did the score for Roger Corman's Wild Angels: the album being produced by Curb, co-written by Curb and Allan, and labelled as being performed mostly by The Arrows. This record is where things get more interesting, yet equally more confusing. Basically, Allan appears to have been Curb's main session guitarist who sometimes remained `hidden' as a session muso, sometimes was subsumed into the identity of a `fake' group, and other times was pushed upfront as Allan with The Arrows to partly capitalize on the success that the original Arrows enjoyed with Apache '65. It seems as though the release of the Wild Angels soundtrack was attributed to Davie Allan & The Arrows largely for this reason, otherwise it would have likely remained an anonymous release by the Mike Curb production machine. Remember also that the original Arrows were a studio band - a bunch of musos getting together for a shot at a hit record, fired through the barrel by producer Curb. Whereas The Ventures `became' a group with the success of Walk Don't Run, The Arrows basically remained a name which was used or suppressed depending on the situation. This might sound unnecessarily detailed, but I'm presenting it as an example of how many now-forgotten American bands throughout the sixties were in a continually shifting state of existence - sometimes under the laboratory conditions of a studio, sometimes in the frenetic and uncontrollable state of live touring under the band's name. It's all caught up in the projected image of being a band when in reality an actual band might not have enjoyed such a stable or accountable existence.

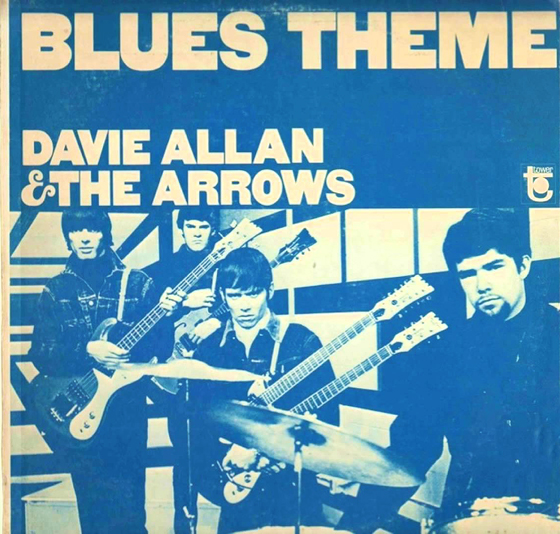

As is well known, Wild Angels was an incredible success, and was seminal in spawning many other biker/drug/Jed/rock mutations (see Chart I). Riding on this success and a few other Curb-produced films hot on its heels (The Devil's Angels and The Born Losers, both 1967) the second Arrows album was released : Blue's Theme (1967). The Arrows on this album are a totally different line-up, most probably the studio musos who worked predominantly on the biker soundtracks for which there was plenty of available work in Hollywood over these few years. (For example, original drummer Larry Brown became associate producer with Curb on this album and quite a few other soundtrack releases on the Tower label.) This second album - like some of the tracks on the Wild Angels and Wild Angels Vol.2 soundtrack albums - really rocks, with Davie Allan carving his niche as the true king of the fuzz guitar. (The overdrive of Allan's fuzz doesn't crop up again with such intensity - or over-the-top corniness - until The Cramps release Human Fly in 1978, where Bryan Gregory's guitar is indistinguishable from the hissing cymbals.) Allan's use of fuzz guitar itself is a sonic metaphor for the revving of motorbikes - the sound effect of which is often mixed into many of the tracks on this album - and peaks with the third Arrows album aptly titled Cycle-Delic Sounds (1968). Allan's fuzz sound perfectly conjures up an imaginable feeling of the roar and drive of a speeding bike, lending his stylistic sound well to films trying hard to fabricate the biker milieu, to give you that feeling that `you are there' making the scene. But while such a sound might in essence be totally theatrical, some of the tracks done by Davie Allan & The Arrows are the noisiest, grittiest, grinding examples of fuzz rock you'll ever hear on record. And all the work of a studio muso produced by Mike Curb.

Such is the paradox of the Curb-Allan collaborations - a paradox sited in the mix of rock ideology and rock music, between what rock `should' be and what it sounds like. Everything about songs like Blue's Theme, King Fuzz, Mind Transferral, Cycle-Delic, Hell Rider and Wild Orgy is totally fabricated and entirely fictionalized, designed for prescribed imagery and a projected audience. But how come they sound so definitive, so driving, so deafening? The options are obvious : (a) either prioritize the conditions of their manufacture (Curb, Corman, Hollywood, exploitation, etc.) and condemn the music, following the belief that anything produced under such conditions can only be false, bankrupt and dismissable; or (b) forget those conditions and accept the music itself - as a dynamic force, a sonic phenomenon, a manifestation of energy. I'm doing the latter. Plus I'm capitalizing upon an historical perspective, because the worst can easily become the best two decades later. Whatever. We have Allen's records now as they stand today, and they stand up well. Their pretence often ends up sounding better than many other examples of the real thing, because in their outright fetishization of the fuzz sound, they aim to give us the sound of rock - the heart of its power.

Forging The Hard Rock Of Led Zeppelin

From America's industrial fabrications we now shift to England's cultural colonizations : the British Invasion, one of the most important underlying agents in the growth of the American rock industry. Would it be inaccurate to say that the British Invasion of 1964-65 was the dawning of the great white guitar hero? Those that the seventies would eventually label as the great rock guitarists all had their roots in early British Beat groups who frantically made Anglicized connections with American r'n'b : Eric Clapton, Pete Townsend, Keith Richards, Jeff Beck, John Mayall, Jimmy Page. Certainly there is a sense that in the UK's reverent invocation of America's blues heritage there was also a welcomed mystification of the figure of the blue man. There seems to have been something heroic implicit in the British r'n'b groups' romantic recouping of this fading Americana : saving the black musical tradition like a great white hunter, and then playing fancy black'n'blue guitar licks to ritualize their heroic capture of the blues. Now, I'm looking back at this period with a certain detachment, born not simply of distance but of a lack of interest. Nonetheless, I propose that virtually the whole history of white rock is based on white artists trying to pull off something black, failing, but creating something new in its place. No country proves this as consistently as England.

I'm foregrounding this notion of white rock - of an innate white inability to engage in such traditions, coupled with a desire to simulate them - to contextualize what I have to say about perhaps the `greatest' of all white rock bands : Led Zeppelin. Rock histories from the seventies - even if begrudgingly - posit Led Zeppelin as one of the greatest rock bands along with The Rolling Stones. Not surprisingly, both groups' histories have largely been determined by their effect upon and presence within the United States, generally regarded as one of the largest and most crucial markets. While both had their roots in the British Invasion of the mid sixties (ie. early Stones and The Yardbirds) their `supergroup' status was consolidated by their appeal in the States throughout the seventies. The invasion never ceased. By and large, America bought the second-hand legacy of the Stones and Led Zep wholesale - especially the Stones, who (perhaps as the result of being British tax exiles) assimilated themselves into country and blues traditions for a rock market that couldn't care less for those traditions. If The Ventures and The Arrows churned out the sound of rock, the Stones affected a sense of heritage, of links and roots with a long tradition. But they only ever gave one the image of such authenticity, inflecting roots rhythms and subtleties with their own brashness and loudness - that is failing, but creating something of their own in place of their original source material. `Roots' was ultimately a stylistic category with a chip on its shoulder about being the real thing. British rock has always carried these kinds of chips on its frail shoulders because it lacked the traditions black musical developments were based on, and in their place bore a `tradition syndrome' where a band like The Rolling Stones could eventually proclaim things like "it's only rock'n'roll but I like it" and feel as though they were carrying the weight of some mythical fore bearers. They only ever carried the weight of their own fawnings and flauntings.

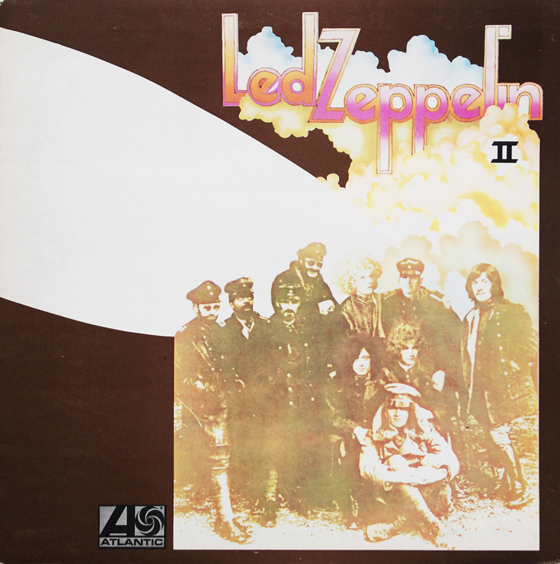

Led Zeppelin are somewhat different. Formed out of the dissolvement of The Yardbirds' second phase, the line-up of Jimmy Page, John Paul Jones, John Bonham and new-boy Robert Plant started out as blues borrowers with heads bowed to the Mississippi-Chicago line, but then quickly changed their perspective on rock. How can I describe this? Let's say if the Stones were an underground Trans-Atlantic tunnel back to the blues, a tributary of tribute flowing back to the Delta, Led Zeppelin built upon the blues, forming solid ground on the Mississippi mud, reshaping, renovating and refurbishing the blues. If the Stones treated rock as the solidness and stabilized strength of blues traditions, Led Zeppelin treated rock as the solidification of the blues as a fluid, musicological development. Hence, Led Zeppelin gave us Hard Rock : rock music beyond the phases of its initial development, and into its decay and corrosion; rock music that acknowledges rock can no longer be created - only adapted, adorned, reconstructed and reconstituted. Rock music that has literally, figuratively, musically and sonically been hardened. And we're talking 1969. We haven't even hit the seventies. Led Zeppelin's first album Led Zeppelin (1969) is a pretty boring album. A noticeably modern edge to its harsh intonations of blues idioms, yet basically hard blues with no outward awareness of how perverse its attempts are to simulate the blues. Things change drastically with their second album released the same year Led Zeppelin II (1969). Take the last track on side 2 of the album - Bring It On Home. It starts with a slow 12-bar blues boogie played on mellow guitar with Plant's close-mike coo-cooing and distant mournful harmonica. `Classic' (or cliched) blues styling. It finishes - but only to be cut into by the much sharper texture of a chunky, distorted riff by Page, played 4 times like a bugle call which heralds the whole band to chug along with the riff, like one big, tight rock machine. A machine that literally steamrolls the thinness of the authentic-styled blues preceding it. This song - like the rest of the album - presents Led Zeppelin as a rock machine built up from the parts designed in various British Beat machine shops during the sixties, where the blues were, in a sense, `beaten' : honed and customized. Led Zeppelin is the finished streamlined, machine - the machine as a prototype in actual motion, rather than the virtual blues flow suggested by rock in the sixties. Empowered with the heaviness and hardness connoted by their name, this machine is used to destroy the blues - not in a negative way, but in a real and positive way, as Led Zeppelin are somehow acknowledging the death of the blues in their hands, transforming its energy by their new machine, accepting that their development of the blues is one of its chameleon changes, not one of its reverent repetitions. Led Zeppelin give us hard rock as a regeneration of the blues - not a discovery or a rebirth, but simply and distinctly another inevitable generation.

OK - lyrically, Led Zeppelin II is all about the blues, man, but it's all a put on. "Squeeze me baby until the juice runs down my legs." "Livin' - Lovin' - She's just a woman." "You're a heartbreaker." Pure image. Cut out and pasted up from a long lineage of bluesmen's lyrics. Plant was no more and no less than a modern pornographic figure for a time when youth was being turned on by how turned on it could be. Like so many white blues-rockers in late sixties/early seventies youth culture, he took the interiorized sexuality of black lyrical poetics and paraded them under the banner of white sexual liberation. The overcoming of cultural oppression recommodified as the release of subcultural repression ; the blues' inner escape to pleasure transmogrified into rock's outer display of consumption. Take Whole Lotta Love : lyrically it's an hysterically sexist tale of a greed for fucking : "Want a whole lotta love - give it to me baby." Pleasure transmogrified into consumption. Can I reduce and dismiss lyrics like that? You bet, because I'm talking about the sound that encapsulates and carries those lyrics, the archeological remains trapped in black vinyl time capsules. Put the records on and their energy is released - their sound - but not their original meaning and effect. Their statements hang today drip-dried and flapping in the wind as dried skin from a bygone epoch of radical gestures. With Led Zeppelin, the lyrics are now rendered humorous, embarrassing, disposable. Not so the music and the sound. Plant's voice often becomes an abstracted texture, a floating sound within the sonic architecture of the song, especially in the infamous, orgasmic middle section of the song where his voice oohs and aahs all over your speakers. But while this section lyrically and metaphorically alludes to a sexual high, it sonically and musically is, if you will, the sound of a horizonless plateau where blues riffs, chords and rhythms can be endlessly transformed. Structure totally collapses here as all manner of blues-rock fragments flash by and swirl around Plant's disembodied moans. This middle section's collapse is a sign - a vision, even - of how rock can be manifested through its deconstitution. Away from the obvious sexual and hallucinogenic highs connoted here, it is a sculptural sketch of the elements, components and materials with which Led Zeppelin would continue to forge and bash together their sound. (Of course, credit should here be given to Jimi Hendrix - the `black white-bluesman' - whose contemporary fluidity in handling, molding and melding these conventions definitely influenced Page.)

Such forged elements are the opening riffs to tracks like Whole Lotta Love and The Lemon Song. They linguistically communicate blues boogie - that's how you identify their riffs stylistically - but their sound and presence are in another dimension from the blues. The sound of Page's guitar is simply too unreal, too weird for it to be conventional electric blues in the mould of, say, Alvin Lee or Johnny Winter (who appear too unimaginative to veer from the conventionally prescribed paths of blues authenticity). It's like Page has listened to the guitar tonings on various Chess recordings of the electric blues (particularly Muddy Waters and Howling Wolf) and acknowledged them as distortions - as radical transformations of the blues' roots, taking them as a sign that the electric blues is itself a new sonic dimension where guitar sounds can be unreal and weird, a space where there is no real blues, only its endless transformation : a `horizonless plateau'. Just listen to the multitude of textures and tones Page employs not only across the album, but also within any one song. He picks up where the mid sixties recordings of Waters and Wolf leave off, and his opening riffs (four out of the album's nine tracks) function like the revving up of the machine, starting the blues up and driving it into its new electrical dimension : hard rock, rock drained of a blues flow.

Structurally, every song on Led Zeppelin II demonstrates the Zep rock machine in motion : shifting gears, controlling the release of its energy and the dynamics of its power. That machine is the rhythm section of Page, Jones and Bonham - possibly the most integrated and fused rhythm section in hard rock. Most of the songs on this album are based on the shifting gears, moving from slow sections to faster sections, displaying the ease with which they can control and channel their energy. What Is And What Should Never Be has a quietly stated verse in order to smash it apart with its chorus. As in Bring It On Home, this vacillation between soft/loud, timid/raging, etc. is commonplace in white rock's sense of theatrics and dramatics, but then in What Is And What Should Never Be a third section - the end section of the song carrying it through to its fade-out - shifts the hard rock machine into another gear. Page punches out a chord sequence which simulates the pattern of a riff - that is, he consolidates the two, fusing them to produce an effect more streamlined then a chord pattern and thicker than a riff. This is a definitive example of how Led Zeppelin `hardened' rock, giving us a statement of congealment and solidification; drying up the mythical sweat of rock'n'roll and replacing it with a textural grout, closing off the blues and sculpting the sound of rock.

This style of `riff rock' is often treated as being a moronic form of rock : repetitive, lumpen, mono-dimensional. Its lineage can be traced from Cream's Sunshine Of Your Love (1967) to its photocopied cut-up for Iron Butterfly's In-A-Gadd-Da-Vida (1968) to the boogie version of Livin' Lovin' Maid's riff for Deep Purple's Black Night (1970) to the application of Page's fused chord-riffing in Black Sabbath's Sweat Leaf (1971). But what distinguishes Led Zeppelin here is the way their rhythm section works together, using the riff as the anchored block, the keystone upon which to build everything else. Boring riff rock always deviates from the power of the riff, throwing in frills, garnishes and arbitrary verse-chorus switches which suggest that they don't fully realize the the power of a good riff. Led Zeppelin's riffs are definitive - as in the restyled Yardbirds' sound of Livin' Lovin' Maid; the steady, measured pacing of Heartbreaker; and drummer John Bonham's chunky 12-bar showpiece Moby Dick. Play these tracks and compare them with the ones I cited above : all of them are `classic' in one way or another, but Led Zeppelin's riffs actually carry through the whole song, because their rock machine runs on those riffs. Led Zeppelin don't just play those riffs : their sound lies within them.

Let's get right to the heart of the matter here : John Bonham. His drumming style is not just powerful and tight - it plays the riffs, the chord sequences, the phrasing of Led Zeppelin's songs. His drumming is not a separate level of the musical construction, but an outline of the songs' rhythmic totality, playing the whole song, not just the beat. In rock music this is a rare and unique approach to rhythmic organization and accompaniment. Bonham's drumming is the most forceful component in the sculpting and structuring of Led Zeppelin's sound because it not only governs the flow of the songs, it also marks the dynamics of their flow; hesitating, anticipating, riding, driving, crashing, halting their development. Listen to that final third section of What Is And What Should Never Be for an instant demonstration of how he closes and opens spaces across the phrasing of Plant's fused chord-riff pattern. It's the same sense of holding back and letting go on the snare which saves the chugging of the Whole Lotta Love riff from degenerating into straightforward boogie. Best of all, listen to the drumming in the second half of Ramble On, with its disorienting delays which confuse on-beats into off-beats and then slips them back into on-beats (a rhythmic styling whose roots lie in Caribbean music with drummers like Sly Dunbar and Dennis Beveled and don't surface elsewhere in white rock until the dub-style patterns of drummers like Budgie [Slits] and Stewart Copeland [Police]). In short, just as Page `hardens' rock into sound, Bonham chisels it into time.

Intermission & An Admonition

Let's backtrack and measure The Ventures, Davie Allan & The Arrows and Led Zeppelin against each other. They all give us the sound of rock, although as I have demonstrated, they arrive at their sound from different perspectives, under different conditions, and with different aims. In their drive toward the production of their music's sound, they nonetheless all operate under a logic of internalization: The Ventures incorporating their identity into their music; Davie Allan & The Arrows working unseen inside the film and recording industries; Led Zeppelin restructuring their sound internally. All are united - though not unified - in their attempts to streamline rock down to its essential characteristics, its definitive elements; each in their own way acknowledges that the sound of rock is an energy that can somehow be brought into being by adhering to its sonic potency and focusing inside the music, away from their/our externalized psycho-socio emotional applications upon its manifestation. Am I saying that they're all `emotionless' in their fabrication, fuzzing and forging or rock? Gimme a break. I'm saying that compositionally, The Ventures, The Arrows and Led Zep delicately yet complexly refine the raw state of rock's rhythmic energy, and that when they process their sound by listening to that energy, they then give us a means by which we too can listen to and feel that same energy. This is neither clinical nor melodramatic; this is how sound works, how sound is, because as mentioned before - "sound is sound and is about sound".

Obviously, I've taken great lengths to present Led Zeppelin's second album as some sort of turning point in the sound of rock. These lengths are I feel necessitated by the outmoded myths which encase Led Zeppelin : the glorified Hammer Of The Gods biography of their dumb debauchery and stereotypical tour antics and obsessions; their Americanized status as a dinosaurian supergroup whose legacy is carried on ungainly by the likes of Foreigner, Journey, Styx, Boston, Loverboy and others too bloated to even contemplate; the general vacuousness of seventies' rock histories which proclaim the band's greatness through an unqualified inflation of prescribed myths; etc.. Plus I'm conscious of being misinterpreted as touting Led Zeppelin as a hip band caught up in the current seventies so-bad-it's-good pastiche revival. Quite simply, I uphold their records as objects listenable through contemporary ears, as items and artefacts which I believe validate what I'm trying to outline here - namely, that Led Zeppelin mark the epiphonic transition (a) from rock'n'roll to rock; (b) from the blues as a black flow to the blues as a white fixture; (c) from the derivations which bore sixties r'n'b to the influences which bore seventies hard rock.

There is a further reason why I'm qualifying Led Zeppelin in this way : they signpost the seventies not as a great, gulping decade of emptiness and nothingness, but as an era working upon that which had already been created; as a sprawling mass which acknowledged that rock'n'roll - even perhaps its modernization, rock - had dried up, tightened up and closed up, leaving only recourse to surfacial and structural application and adaptation, and to reject rock as myth and ideology and treat it directly as sound. To deride the seventies as merely `neither-the-fifties-sixties-nor-eighties' is dumb, stupid and downright brainless. The seventies is truly one of the darkest of rock's cultural terrains - not because there is anything mysteriously hidden in its chalky, fluorescent limelight, but simply because there has been a general avoidance of coming to grips with the values that decade fostered. I mean, have we really had to wait until the nineties to do this? Is the sixties counter-cultural legacy truly so oppressive that the seventies be continually posited as the awakening from the beautiful dream into its ugly daylight?

Perhaps it's just a generational phenomenon. I can remember getting interested in music when I was about 11 or 12 in 1971/2, and as was the probable case with many others, didn't get a real sense of rock history until the punk explosion of 1976/7 wherein I learned history in reverse. These pages - long and rambling through they may be - is my reversal of that history, back through the myths which never affected or impressed me, back into the white-est and darkest of all continents : the seventies, where the sound of rock overrides rock itself.

Text © Philip Brophy. Images © respective copyright holders.