A Lust for Violence

Curated film programme for Melbourne International Film Festival - 2000Catalogue essay

Since retrospectives on Seijun Suzuki's work as early as one at the Edinburgh Film Festival in 1989, a peculiar Westernized mythology has followed his steady rise to cultdom over the ensuing decade. We are told he was fired from the mainstream production company Nikkatsu (key purveyor of 60s' roman porno or 'pink' movies with shades of S&M) because his films were deemed 'incomprehensible'. We are told he crazily mixes humour into his narratives, and that his films are excessively and almost irrationally stylized. And he has been often compared with lauded American mavericks like Robert Aldrich and Sam Fuller.

But to best understand Suzuki and what he represents, one needs to comprehend the explosive culture of postwar Japan. Or, if you are attuned to the sensibilities of Japan's pop culture, then Suzuki's fevered amalgams of hysterical action cinema would be recognizable as ambassadors of that milieu. But in the West we still don't understand pop culture: we think it either has to be parodied by politically-correct comedians or couched in social theory by smarmy journalists and TV presenters - as if pop culture needs to be explicated and rendered intelligible. As if authors, artists and auteurs are the only ones to make statements about anything.

Suzuki's cinema - strictly not 'his', but he is an important figure in its apparition across 40 genre films between 1956 and 1967 - is particularly complex and fascinating because he applied the harsh sardonic perspective of Japanese literary figures from the 20s and 30s who became embroiled in WWII while being opposed to many of its brutal dehumanizing facets. Standard intelligentsia practice for the celebrated likes of Kurosawa, Imamura and Oshima - but Suzuki was making populist, successful genre movies. Imbedded deep in the lurid density of so-called 'B-grade' genre production, his succulent films grew fetid in the dark of public cinemas, away from the glare of internationalist festival spotlights. He stands as one of many unacknowledged figures who contextualizes the existential ephemera between Masaki Kobayashi's A Soldier's Prayer (1961) and Kitano Takashi's Sonatine (1993). Looking at Suzuki's confronting and halting combination of sex and violence in a contemporary climate, his films are less curious models of auteurist valiance and more intense and incisive statements of what genre film making is all about: a heady deliverance of sensation and manipulation.

You may not make much sense out of this small sampling of the genre films of Seijun Suzuki. But it is worth trying to view them not in a tacky 'rebel/loner' light, nor as 'wild and weird' simply because they don't ape the naturalism which has stranglehold the dramatic arts for the past thirty years. Some pointers. Firstly, Suzuki's films mix sex, violence, humour, pathos, critique and anarchy in a non-holistic way. Do not expect resolution, reprisals or reprimands. You have to shift gears with the seemingly amoral narratives as they spin, lurch and turn along a foreign road. Secondly, Suzuki's films are not unified in style, content or even tone. Directing between 3 to 6 films a year across a decade, his films form an off-kilter map of impulses, eruptions, quirks, banners, gestures. Catch them as they are expelled on-the-run, carelessly and gratuitously, but always with maximum impact. Thirdly - and this should be part of any primer on Japanese pop cinema - most everything that seems funny is achingly pathetic, and most everything which makes you shudder is but a flippant and cursory incidental. Please invert your mind before taking in these movies, and chortle at the expense of your own stupidity.

Each year, the imported oddity we call 'Japan' grows. So many images, sounds, events and sensations are welcomed into the West as we seem to be caught in an endless fascination with Japan's fractured reflection of ourselves in both retro and techno guises. This retrospective on Seijun Suzuki irresponsibly adds to that glut. Yet the beauty and value of our indiscriminate consumption can hopefully infect us and addict us to the vast uncovered spread of Japanese pop culture from the last 50 years and beyond. Like the disenchanted 'wanderer' figure who traverses both Suzuki's yakuza films and that Japanese genre in general, we too could flow through its landscape to the twang of an electric koto.

Thanks to MIFF festival director Sandra Sdraulig, programme co-ordinator Brett Woodward & Mike Campion. Further reading: Paul Willemen & Jim Hickey - "The Films of Seijun Suzuki" in The 1988 Edinburgh Film Festival Catalogue, Edinburgh, 1988; Simon Field & Tony Rayns (ed) - Branded To Thrill, ICA, London, 1994Programme

-

Detective Bureau 2-3: Go To Hell, Bastards!

aka Detective Bureau 2-3: Down With The Wicked

1963

Written by Iwao Yamazaki (based on a novel by Haruhiko Oyabu)

Written by Iwao Yamazaki (based on a novel by Haruhiko Oyabu)

Directed by Seijun Suzuki

Directed by Seijun Suzuki

Starring Jo Shisido

Starring Jo Shisido

Music by Haruo Ibe

Music by Haruo Ibe The global phenomenon of James Bond is an archetypal instances of 60s' audiovisual brashness. The sheer loudness and pictorial noise of the first Bond films and their ironic self-consciousness reverberated throughout world cinema, creating many a transcultural mutant in the espionage genres. Far from being an imperialist colonizing trend, the theatrical excess of the Bond films presented many non-Anglo cultures with a Pop Art canvas onto which their own frenetic stylistic exercises could be splashed. Suzuki's Detective Bureau stands as a delicious Nippon Pop version. Jo Shisido - a regular star in Suzuki's cinema - plays private eye Hideo Taijima, who in a dizzying duplicitous patchwork of plot flip-flops infiltrates a yakuza gang and tears it asunder. Like many Japanese 60's action heroes, Shisido has been vastly underrated. While his acting by our sophisticated standards may be less than perfect, his screen presence in notable, as is his physical prowess. In contrast to American cinema, Japanese action heroes can move with great agility and precision. This aspect of their presence accounts for the balletic feel of their scenes. Suzuki has always favoured moving his action stars through roving widescreen pictorialism as a re-instatement of Kabuki's horizontal stage. He doesn't just set up his images in stilted arty fashion: he choreographs its transitions around the ways in which Shisido hurls, dives and zaps through scenes, sometimes with the aid of unlikely mechanisms. Detective Bureau is a great place to start on the delirious road to Suzukimania.

The global phenomenon of James Bond is an archetypal instances of 60s' audiovisual brashness. The sheer loudness and pictorial noise of the first Bond films and their ironic self-consciousness reverberated throughout world cinema, creating many a transcultural mutant in the espionage genres. Far from being an imperialist colonizing trend, the theatrical excess of the Bond films presented many non-Anglo cultures with a Pop Art canvas onto which their own frenetic stylistic exercises could be splashed. Suzuki's Detective Bureau stands as a delicious Nippon Pop version. Jo Shisido - a regular star in Suzuki's cinema - plays private eye Hideo Taijima, who in a dizzying duplicitous patchwork of plot flip-flops infiltrates a yakuza gang and tears it asunder. Like many Japanese 60's action heroes, Shisido has been vastly underrated. While his acting by our sophisticated standards may be less than perfect, his screen presence in notable, as is his physical prowess. In contrast to American cinema, Japanese action heroes can move with great agility and precision. This aspect of their presence accounts for the balletic feel of their scenes. Suzuki has always favoured moving his action stars through roving widescreen pictorialism as a re-instatement of Kabuki's horizontal stage. He doesn't just set up his images in stilted arty fashion: he choreographs its transitions around the ways in which Shisido hurls, dives and zaps through scenes, sometimes with the aid of unlikely mechanisms. Detective Bureau is a great place to start on the delirious road to Suzukimania. -

Youth of the Beast

aka Wild Youth & The Brute

1963

Directed by Seijun Suzuki

Directed by Seijun Suzuki

Written by Ichiro Ikeda & Tadaaki Yamazaki (based on a novel by Haruhiko Yamazaki)

Written by Ichiro Ikeda & Tadaaki Yamazaki (based on a novel by Haruhiko Yamazaki)

Starring Jo Shisido

Starring Jo Shisido

Music by Hajime Okumura

Music by Hajime Okumura Jo Shisido is Jojini Mizuno: disgraced ex-cop convicted for illicit dealings. Like a stubborn drunkard, he crashes his way into the most unimaginable scenarios, unleashing brutality, anguish, psychosis. His violent and erotic appearances redefine the dramatic entrance. In the traditions of kabuki's operatic surfeit and the samurai movie's penchant for visualizing the lone wander in mythical relation to his surroundings, Suzuki glorifies Mizuno's stature in high-theatrical repose. Just as each yakuza (including Mizuno pretending to be one) is typified by a specific psychotic blend, so are their environments breathtaking, surreal, overwhelming. But is this film really 'over the top'? Or is it an example of a film that has nothing whatsoever to do with what we have historically defined as 'naturalistic'? Surely one must note that the apparent excessiveness in this example of Suzuki's assured staging and orchestration of audiovisual elements is consistent, measured and controlled. To maintain its hysteria - to modulate its continual gushing and billowing moments - is no mean feat. Plus, one could only do so through knowing the total theatrical logic under which such hysteria operates. Everything in Youth of the Beast indicates this, from its memorable vistas of windswept urbania to some of the coolest nightclub settings in the cinema. Suzuki's 'artificialism' here predates the surge of similarly hyper-plastic decors which characterized the gaudy collisions between cinema, MTV and postmodernism in American, British and Japanese cinema from the 80s. No mere protracted exercise in style, Youth of the Beast is set in a psychologically aberrant landscape wherein everyone has been pushed 'over the top'.

Jo Shisido is Jojini Mizuno: disgraced ex-cop convicted for illicit dealings. Like a stubborn drunkard, he crashes his way into the most unimaginable scenarios, unleashing brutality, anguish, psychosis. His violent and erotic appearances redefine the dramatic entrance. In the traditions of kabuki's operatic surfeit and the samurai movie's penchant for visualizing the lone wander in mythical relation to his surroundings, Suzuki glorifies Mizuno's stature in high-theatrical repose. Just as each yakuza (including Mizuno pretending to be one) is typified by a specific psychotic blend, so are their environments breathtaking, surreal, overwhelming. But is this film really 'over the top'? Or is it an example of a film that has nothing whatsoever to do with what we have historically defined as 'naturalistic'? Surely one must note that the apparent excessiveness in this example of Suzuki's assured staging and orchestration of audiovisual elements is consistent, measured and controlled. To maintain its hysteria - to modulate its continual gushing and billowing moments - is no mean feat. Plus, one could only do so through knowing the total theatrical logic under which such hysteria operates. Everything in Youth of the Beast indicates this, from its memorable vistas of windswept urbania to some of the coolest nightclub settings in the cinema. Suzuki's 'artificialism' here predates the surge of similarly hyper-plastic decors which characterized the gaudy collisions between cinema, MTV and postmodernism in American, British and Japanese cinema from the 80s. No mere protracted exercise in style, Youth of the Beast is set in a psychologically aberrant landscape wherein everyone has been pushed 'over the top'. -

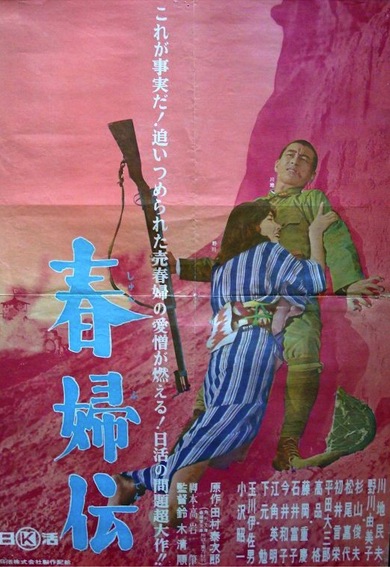

Story Of A Prostitute

aka Joy Girls

1965

Directed by Seijun Suzuki

Directed by Seijun Suzuki

Written by Hajime Takaiwa (based on a novel by Taijiro Tamura)

Written by Hajime Takaiwa (based on a novel by Taijiro Tamura)

Starring Yumiko Nogawa

Starring Yumiko Nogawa

Music by Naozumi Yamamoto

Music by Naozumi Yamamoto Some sequences in Story of a Prostitute are so achingly beautiful, they scar the mind. In fact, I would argue that Suzuki's most powerful films revolve around women. OK - so they're always prostitutes in one way or another, but a potent trait of Japanese cinema has been its portrayal of the geisha in modern guise, and along with Suzuki's own Gate of Flesh (1964), Story of A Prostitute is a landmark in psycho-sexual portraiture. But don't expect to tug your emotional crotch for any 'hooker-with-a-heart-of-gold' here. Story of a Prostitute is the anti-matter version of the moving yet comparatively cashmere Paradise Road. In place of a cathartic and healing resolution, Story of a Prostitute self-immolates in dramatic anguish like a scar inflamed by the heated knife which attempts to cauterize it. Its tragic story is set against the Manchurian war front of 1937 and centred around the splayed love expressed and commodified by 'comfort women' incarcerated in a hellish pornographic outpost for the Japanese military. Harumi - played with a mix of volatile hatred and impassioned desire by Yumiko Nogawa, star of Gate of Flesh - enters this inferno of bodily abjection with a will to disempower Man, and commits to this through a savage extinguishing of her own humanity . She crashes through love like Suzuki's yakuza tear through the paper walls of their gambling dens. She swims in her saturated bed and imagines Man as a draining stream of faceless limbs. She lies with her unconscious lover in a bombarded trench and hears the quietude of a village near the ocean. The unexpected poetry and engulfing prose with which she is pictured, intoned and imagined will leave you hung dry and emptied. File with Vagabonde, Georgia, I Spit On Your Grave - but label Suzuki.

Some sequences in Story of a Prostitute are so achingly beautiful, they scar the mind. In fact, I would argue that Suzuki's most powerful films revolve around women. OK - so they're always prostitutes in one way or another, but a potent trait of Japanese cinema has been its portrayal of the geisha in modern guise, and along with Suzuki's own Gate of Flesh (1964), Story of A Prostitute is a landmark in psycho-sexual portraiture. But don't expect to tug your emotional crotch for any 'hooker-with-a-heart-of-gold' here. Story of a Prostitute is the anti-matter version of the moving yet comparatively cashmere Paradise Road. In place of a cathartic and healing resolution, Story of a Prostitute self-immolates in dramatic anguish like a scar inflamed by the heated knife which attempts to cauterize it. Its tragic story is set against the Manchurian war front of 1937 and centred around the splayed love expressed and commodified by 'comfort women' incarcerated in a hellish pornographic outpost for the Japanese military. Harumi - played with a mix of volatile hatred and impassioned desire by Yumiko Nogawa, star of Gate of Flesh - enters this inferno of bodily abjection with a will to disempower Man, and commits to this through a savage extinguishing of her own humanity . She crashes through love like Suzuki's yakuza tear through the paper walls of their gambling dens. She swims in her saturated bed and imagines Man as a draining stream of faceless limbs. She lies with her unconscious lover in a bombarded trench and hears the quietude of a village near the ocean. The unexpected poetry and engulfing prose with which she is pictured, intoned and imagined will leave you hung dry and emptied. File with Vagabonde, Georgia, I Spit On Your Grave - but label Suzuki. -

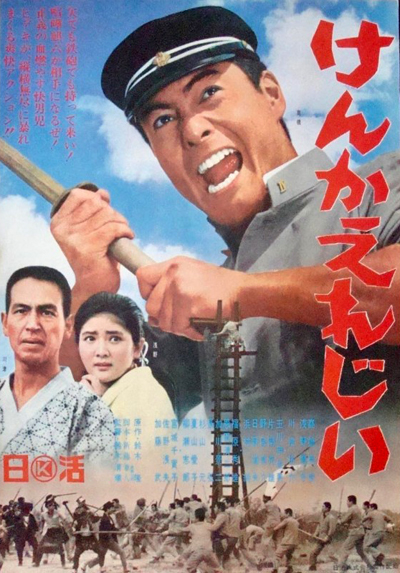

Fighting Elegy

aka Violence Elegy, Elegy for a Quarrel & Scuffle

1966

Directed by Seijun Suzuki

Directed by Seijun Suzuki

Written by Kazu Otsuka

Written by Kazu Otsuka

Starring Hideki Takahashi

Starring Hideki Takahashi

Music by Naozumi Yamamoto

Music by Naozumi Yamamoto One of Suzuki's most intellectual yet perplexing films, Fighting Elegy could be somewhere between Porky's and Zero For Conduct. It follows the delinquent exploits of Kiroku Nanbu (Hideki Takahashi) as he rebelliously claws his way through high school hell in Okayama in 1935. In its implosion brought about by relished violence and politicized epiphanies, the viewer is left sifting through the causal action represented and how it relates to a national psyche. It must be remembered, though, that Fighting Elegy is part of both a time and a culture which rarely shied away from intensely depicting the brute force with which Japanese society brought the individual into line. Many films from Japan's turbulent 60s' cinema history have floated beyond our reach in the West - something for which the weak-at-heart should be thankful. Yet no matter how gratuitous the pummelling and pugilism seems in Fighting Elegy, it sensationally captures the pent-up frustration which links sex to violence in young males. Where else but in Japanese cinema would you have so many references to erections and masturbation without resorting to bawdy jokery? Humour is ever present in this most ironic of Suzuki's films, but be prepared for its displacement and dramatically asynchronous discharge. Likewise, note the quietly chilling ending and how it positions the right-wing radical nationalist Kita Ikki as the spiritual embodiment of youthful anger and its potential channelling into purposeful action.

One of Suzuki's most intellectual yet perplexing films, Fighting Elegy could be somewhere between Porky's and Zero For Conduct. It follows the delinquent exploits of Kiroku Nanbu (Hideki Takahashi) as he rebelliously claws his way through high school hell in Okayama in 1935. In its implosion brought about by relished violence and politicized epiphanies, the viewer is left sifting through the causal action represented and how it relates to a national psyche. It must be remembered, though, that Fighting Elegy is part of both a time and a culture which rarely shied away from intensely depicting the brute force with which Japanese society brought the individual into line. Many films from Japan's turbulent 60s' cinema history have floated beyond our reach in the West - something for which the weak-at-heart should be thankful. Yet no matter how gratuitous the pummelling and pugilism seems in Fighting Elegy, it sensationally captures the pent-up frustration which links sex to violence in young males. Where else but in Japanese cinema would you have so many references to erections and masturbation without resorting to bawdy jokery? Humour is ever present in this most ironic of Suzuki's films, but be prepared for its displacement and dramatically asynchronous discharge. Likewise, note the quietly chilling ending and how it positions the right-wing radical nationalist Kita Ikki as the spiritual embodiment of youthful anger and its potential channelling into purposeful action. -

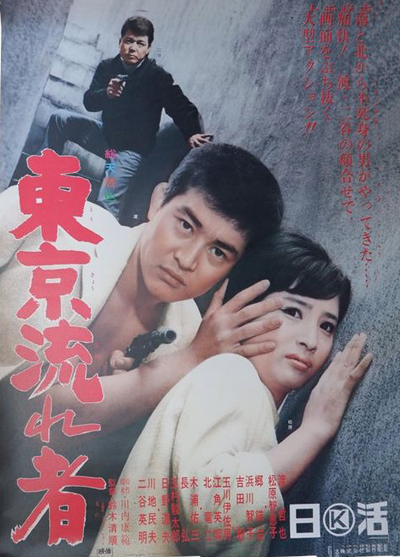

Tokyo Drifter

aka The Man From Tokyo

1966

Directed by Seijun Suzuki

Directed by Seijun Suzuki

Written by Yasunori Kawauchi (based on his novel)

Written by Yasunori Kawauchi (based on his novel)

Starring Tetsuya Watari

Starring Tetsuya Watari

Music by So Kaburagi

Music by So Kaburagi A must-have series of Japanese CDs throughout the 90s is The Dark Side of Pop. It focuses on the weird songs recorded by movie stars, ex-boxers, gangsters and freaky-nobodies from the 60s and 70s. Many of them were huge; some went nowhere; all were 'incredibly strange'. Tokyo Drifter is a postcard from that uniquely Japanese cross-over between pop music and cinema. Starring male idoru singer Tetsuya Watari, the film is like an extended video clip for his maudlin, twanging yakuza ballad. Much has been made about the use of his theme song throughout the film and how he sings and whistles it himself prior to gunning down hordes of rival gangsters - but don't forget that Suzuki's cinema grows from the country that gave us karaoke: singing publicly in seemingly inappropriate contexts is commonplace. Even though Tokyo Drifter is like a yakuza version of West Side Story, its innate sensibility emanates from Japan's cherish of the ballad. Aesthetically, the film honours the ballad, and dresses its presence - the poses of its singer and the lushness of the song's orchestration - ornately, lusciously, vividly. The many club, bar and office scenes are crucial to this in that much of the violence is doubly staged: deaths occur on gaudy sets, against wacky back-drops and in over-designed interiors. While the samurai genre is basically a network of tensions struck between the bushido code and the samurai's nomadic release from deigned honour, the yakuza genre explores the displaced terrain across which killers roam in search of meaning. Testuya's singing in Tokyo Drifter is the mournful refrain from that emotional ground; it is the sound of his unshed tears melting the snow.

A must-have series of Japanese CDs throughout the 90s is The Dark Side of Pop. It focuses on the weird songs recorded by movie stars, ex-boxers, gangsters and freaky-nobodies from the 60s and 70s. Many of them were huge; some went nowhere; all were 'incredibly strange'. Tokyo Drifter is a postcard from that uniquely Japanese cross-over between pop music and cinema. Starring male idoru singer Tetsuya Watari, the film is like an extended video clip for his maudlin, twanging yakuza ballad. Much has been made about the use of his theme song throughout the film and how he sings and whistles it himself prior to gunning down hordes of rival gangsters - but don't forget that Suzuki's cinema grows from the country that gave us karaoke: singing publicly in seemingly inappropriate contexts is commonplace. Even though Tokyo Drifter is like a yakuza version of West Side Story, its innate sensibility emanates from Japan's cherish of the ballad. Aesthetically, the film honours the ballad, and dresses its presence - the poses of its singer and the lushness of the song's orchestration - ornately, lusciously, vividly. The many club, bar and office scenes are crucial to this in that much of the violence is doubly staged: deaths occur on gaudy sets, against wacky back-drops and in over-designed interiors. While the samurai genre is basically a network of tensions struck between the bushido code and the samurai's nomadic release from deigned honour, the yakuza genre explores the displaced terrain across which killers roam in search of meaning. Testuya's singing in Tokyo Drifter is the mournful refrain from that emotional ground; it is the sound of his unshed tears melting the snow. -

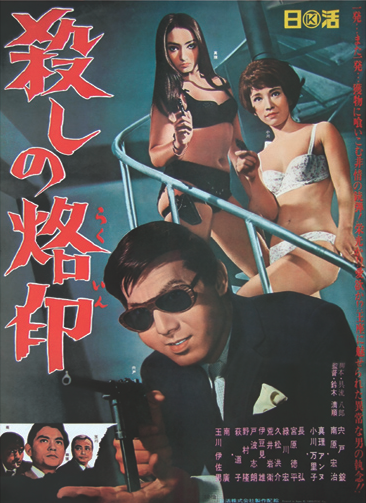

Branded To Kill

1967

Directed by Seijun Suzuki

Directed by Seijun Suzuki

Written by Hachiro Guryu

Written by Hachiro Guryu

Starring Jo Shisido

Starring Jo Shisido

Music by Naozumi Yamamoto

Music by Naozumi Yamamoto Possibly Suzuki's most infamous film, Branded To Kill certainly retains its searing punch after repeated viewing. Curiously, it is also his least 'Pop Art' and quivers with a heightened otherness. While proclaiming the stylistic hallmarks of his neo-kabuki cinedrome of violence, it stands out in his oeuvre due to its unsettling importation of Gothic sensibilities and an atypically atonal score by Yamamoto into what otherwise would be standard hitman fare. Combined with some suitably chiaroscuro cinematography, its story of a bizarre psycho-sexual relationship between Hanada Goro (Jo Shisido) - he gets hard from the smell of hot rice - and the necrophiliac Annu (Misako Nakajo) - she sleeps on a bed of dead birds - is closer to 60s' horror manga than any James Bond film. Branded To Kill is actually a psychological symphony across a range of genres and styles. After mimicking a noir killer-for-hire scenario, it shifts into a desolate front guard gun battle in gaping tunnels and surreal bunkers, resembling Robert Aldrich's hyper-existential Attack! (1966). Shortly, a long sexcapade follows at Hanada's hotel with his 'wife' in a polysexual splattering of orgasms across a fractured domestic environment. This section is quintessentially Japanese in its erotic tone, hovering somewhere between Oshima's In The Realm of The Senses (1976) and Bertolucci's Last Tango In Paris (1974). But with the appearance of Annu, the film morphs into a sister version of Hitchcock's American Gothic Psycho (1960). And as it spirals along with Hanada into his seething inner turmoil, the film plummets into a cut-up of Welles' The Lady From Shanghai (1954). Truly, this is an avant garde beast clothed in Pop. If, after watching Branded To Kill, you can't get a sense of the kanji of Japanese pop culture and its absolute indifference to the West's incessant debate between 'high and low culture' - give up.

Possibly Suzuki's most infamous film, Branded To Kill certainly retains its searing punch after repeated viewing. Curiously, it is also his least 'Pop Art' and quivers with a heightened otherness. While proclaiming the stylistic hallmarks of his neo-kabuki cinedrome of violence, it stands out in his oeuvre due to its unsettling importation of Gothic sensibilities and an atypically atonal score by Yamamoto into what otherwise would be standard hitman fare. Combined with some suitably chiaroscuro cinematography, its story of a bizarre psycho-sexual relationship between Hanada Goro (Jo Shisido) - he gets hard from the smell of hot rice - and the necrophiliac Annu (Misako Nakajo) - she sleeps on a bed of dead birds - is closer to 60s' horror manga than any James Bond film. Branded To Kill is actually a psychological symphony across a range of genres and styles. After mimicking a noir killer-for-hire scenario, it shifts into a desolate front guard gun battle in gaping tunnels and surreal bunkers, resembling Robert Aldrich's hyper-existential Attack! (1966). Shortly, a long sexcapade follows at Hanada's hotel with his 'wife' in a polysexual splattering of orgasms across a fractured domestic environment. This section is quintessentially Japanese in its erotic tone, hovering somewhere between Oshima's In The Realm of The Senses (1976) and Bertolucci's Last Tango In Paris (1974). But with the appearance of Annu, the film morphs into a sister version of Hitchcock's American Gothic Psycho (1960). And as it spirals along with Hanada into his seething inner turmoil, the film plummets into a cut-up of Welles' The Lady From Shanghai (1954). Truly, this is an avant garde beast clothed in Pop. If, after watching Branded To Kill, you can't get a sense of the kanji of Japanese pop culture and its absolute indifference to the West's incessant debate between 'high and low culture' - give up.