Death of the Natural

Death of the Natural

Picturing Atonality Part 2

published in The Wire No.169, March, 1998, LondonThose stabbing violins from PSYCHO (1960, directed by Alfred Hitchcock). Everyone knows them. No one can vocally imitate them. A million film's mimic them. Far more than a residual icon of popular culture, Bernard Herrmann's simple yet mortally effective musical device contains what is perhaps the most profound treatise on the production of music this century. Here's why.

Hallowed for its mystical properties, the violin's design and purpose provides us with a textual morbidity which few people recognize. Take a living tree; chop it down and hack it apart; re-shape it in the form of a limbless female torso; gouge a vaginal hole to create an eviscerated resonating chamber; take the hair of a horse's tail and fashion a tense bow; gut a cat and stretch its innards into thin strings; add some detailing to affect an ornate piece of domestic furniture. Then scrape the horse's tail across the dead cat's remains and generate a howling screech. But to elevate your destructive act to a creative one, you must obey a harmonic code, and practice for years until you can effect pitch-controlled melody. As a frail, gorgeous, feminine tone emits from this macabre instrument, you will be hailed as a producer of music, art, beauty and truth. Viewed this way, the violin is a perfect symbolic microcosm of the desperate measures through which European High Art has since the Enlightenment made much ado about taming nature through such violence to produce a beauty predicated on death, destruction and decay.

How fitting that Herrmann - for his PSYCHO score - figures the specious glory of the violin as a modernist, wail of multiplied clashing frequencies to accompany the image of a naked woman being stabbed repeatedly in the shower by a transvestite who has mummified his murdered mother. Once again, Herrmann's score uses music as but one vocabulary which must negotiate a textual relationship with sound and noise. Despite its hysterical and excessive appearance, the score to PSYCHO is no mere caricature of Otherness: it musically simulates the collapse of meaning which propels its character psychosis, using the venerated violin as a site of musical significance, and thereby generating noise from an instrument designed specifically to transcend noise.

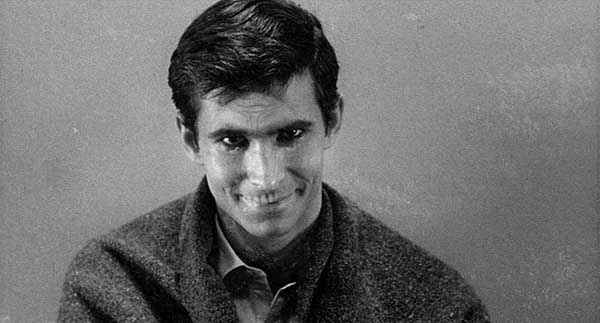

Throughout PSYCHO, Herrmann orchestrates chaos, conducts adrenalin, tempers aggression, builds nervousness. When Marion (Janet Leigh) drives towards her doom in the pouring Gothic rain, the windscreen wipers cut the teeming shower like maniacal batons in time with the main theme (forcasting the means by which she will die). When Norman (Anthony Perkins) starts to loose his grip on things when casually chatting with Marion, the score performs a delicate unfurling of modulating atonal motifs which symbolise Norman's hazed and phased thought processes. Higher frequencies on the violins mark him clearing his head; lower drones by the double cellos echo the rotting, ground swell of his mother's hold on his mental faculty. Running at around 17 minutes and subtitled "A Narrative For Orchestra" on the official stereo recording for Decca in the early 70s, there is not a single gratuitous, vague, ill-prompted or ornamental note in the whole score. Herrman is never an impressionist, lyricist or even expressionist; he remains a passionate structuralist whose sense of musical logic, psychoacoustics and dramatic temporality marks him as the most modern and most cinematic of film scorers this century.

Whether or not other composers and directors are cerebrally fixed on this does not dilute the essential quality of Herrmann's work which propels a network of spindly shards and knots through numerous 'psycho' movies since. A knowing revision of Herrmann's contribution to musical psychosis is found in the selection of music for Stanley Kubrick's THE SHINING (1980) - in particular, the excerpts from Krystof Penderecki's "De Natura Sonoris" (1966) and "Polymorphia" (1961). Penderecki's work - possibly more so than the intricate transpositions of insect harmonics and frequencies which gives Bela Bartok's later work its fetid, corpulent richness - celebrates the abject violence of nature is all its cosmological eventfulness. Certainly the orchestra has for at least three centuries used its mass and size to create intimidating landscapes, portraits, visions and journeys which evoke the scale of nature's destructive, creative and rejuvenative powers. But Penderecki's archly modernist postwar decimation of harmonic fixture encodes the sonic detailing of the destruction of the orchestra itself - overtly signified by the agressive scaping of the sring section. Through his direction of performer technique, Penderecki works beyond abstraction to a pure material essence as he forces the players of his score to rip open that polished wood detailing on the violin and expose the shrieking soul trapped in its necrophiliac casing. His infamous "Threnody For The Victims Of Hiroshima" (1960) is a desolate and deafening abstract narrative which many people liken to an atomic bomb blast before they know the title of the work.

As Jack Torrens (Jack Nicholson) creeps up the stairs swinging a baseball bat at his wife in THE SHINING, Penderecki's strings slice the air like deadly bursts of steam expelled through Jack's flaring nostrils. Elsewhere, during unsettling moments where Jack is slowly becoming possessed by the psychotic ghost which haunts the hotel, the orchestra rumbles like a needle left in a Deutsche Gramophone disc while a mild earth tremor vibrates the diamond stylus. Most importantly, THE SHINING eschews cues in favour for asynchronous passages which extemporise the narrative and sculpt a dramatic ambience wherein a character's psychosis becomes an aura which taints, tinges and terrifies all other existence in its space. As with Herrmann's charting of the surges in Norman's emotional instability, Penderecki's passages function as a soundtrack to the core synaptic overloads which induce psychosis, creating a hyper-material effect of scoring neural and metabolic movement instead of coding harmony to match known social norms and deviations. In an ironic but committed manner, Kubrick is sourcing the High Art realm of serious composition to provide first degree sonic material to shape the aural world of THE SHINING. (Though it must be pointed out that Herrmann did not copy Penderecki, and that both were working from different angles to arrive at the destruction of violin technique by 1960. Furthermore, William Friedkin's THE EXORCIST (1971) contains a canny selection of excerpts from Penderecki's "Polymorphia" (1961), "Canon For Orchestra & Tape" (19?) & "String Quartet #1 (1960); Anton Webern's "Five Pieces For Orchestra Opus 10" (1925) and George Crumb's "Threnody 1: Night of the Electric Insects" (19?) to create an paranormal contra-social domain for its tale of demonic possession.)

The atonality fraternity of PSYCHO, THE EXORCIST and THE SHINING is so much more than the odd bump of chromatic progression to signify the absence of melodious accord. They are astute musicalisations of ECG read-outs, charting the core impulses of moments well beyond the moral conventionalism of 'character motivation'. A film which captures this mystery of apparently 'unmotivated action' - so confusing to those steeped in literary convention and classical story-telling forms - is Agnes Varda's VAGABONDE (1985). The score by Joanna Burzdowicz could superficially be described as Webernesque in its austere and skeletal interlocking of chamber instruments climbing over each other in serialist fashion, however that does not accurately qualify its precise contribution to the film. The film's eponymous unnamed character is a young woman (Sandrine Bonnaire) hitching rides around Southern France, living in fields, shacking up with whoever she meets, stealing food when the moment presents itself. Using a cast of local non-actors, the film's narrative is appropriately transient: it opens with the young woman's body discovered in a farm ditch, then follows a presumed narrative of her last few weeks based on casual interviews with those whose paths she crossed in the lead up to her undramatic death.

This means that five minutes into the film, you're following a story of which you know the outcome: this woman will die. As the story unfolds, one is brought into close proximity with the transient flow of life which governed both the young woman's philosophy and the conditions under which she existed. The accompanying music marks her actions and reactions with a haunting, stilling quality. A strange draining of pathos and seeping of affection fatally paints the young woman as a ghost: a fading being whose erasure is proportionately framed by people's wavering feelings towards her and her response to their lack or surplus of affection. Emotional confusion reigns, as the music's atonality and arch serial escalations stall one from committing to her character in one way or the other. Soliciting neither a stream of ennui nor a fissure of existentialism, VAGABONDE creates a vacuum within which harmony is posited as a device deemed entirely incapable of coding the complexity of people's shifting emotional states. (One of the other very few films which works its atonal score along these lines is the rich but often near-impenetrable film THE CONVENT - 1992, directed by Manuel Olivera - which uses whole uninterrupted movements from one of Stravinsky's more austere violin concertos with perplexing yet magical effect.)

Perhaps this is why music cues are so neurotically Romantic in their Hanna Barbera reduction of humanist traits: when audiences cannot 'identify' with on-screen characters, they have to delve into themselves to question why they can't. And most people probably seem happy to pretend they can relate to others, when in their social reality they may be totally incapable of such engagement. Perceived in this modern and somewhat harsh light, cinematic atonality - whether serialist, abstractionist or hyper-material - can traumatize the listener deeply when it is attached to the representation of human activity and discourse. While films like PSYCHO, THE EXORCIST and THE SHINING can be accepted through their excessive rendering of psychotic and aberrant personalities - the Other which we hold at a safe distance, which we desperateky believe we clearly are not - films like VAGABONDE and THE CONVENT can make one realize what little psychological territory we have covered in the musical characterization of film scores this century.

Text © Philip Brophy 1998. Images © respective copyright holders