Background

Installation view - National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne © 2006

Japan boasts the largest manga (comics) and anime (animation) industries in the world. The culture which has developed from this peculiar post-atomic fusion of eastern calligraphic sensibility and western narrative iconography is an active and vital demonstration of a non-Eurocentric postmodernism. Instrumental figure in the originating history of both art forms and media is Osamu Tezuka (1928 - 1989).

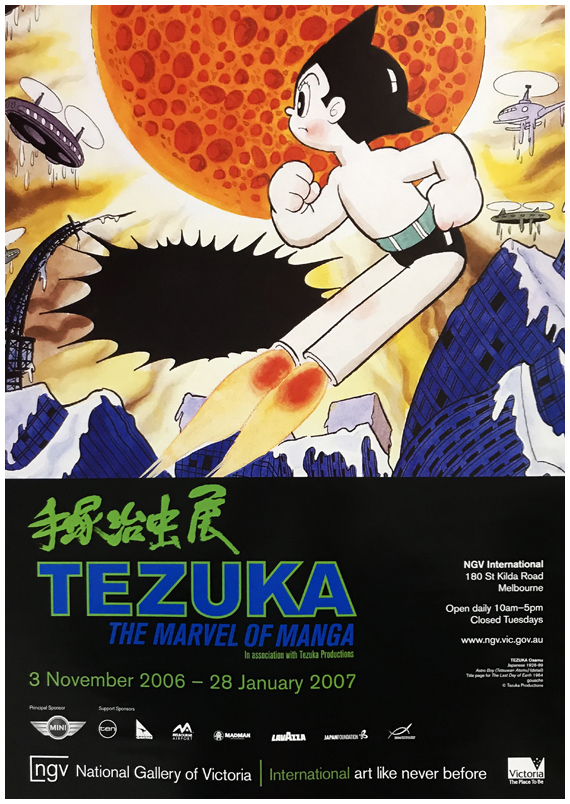

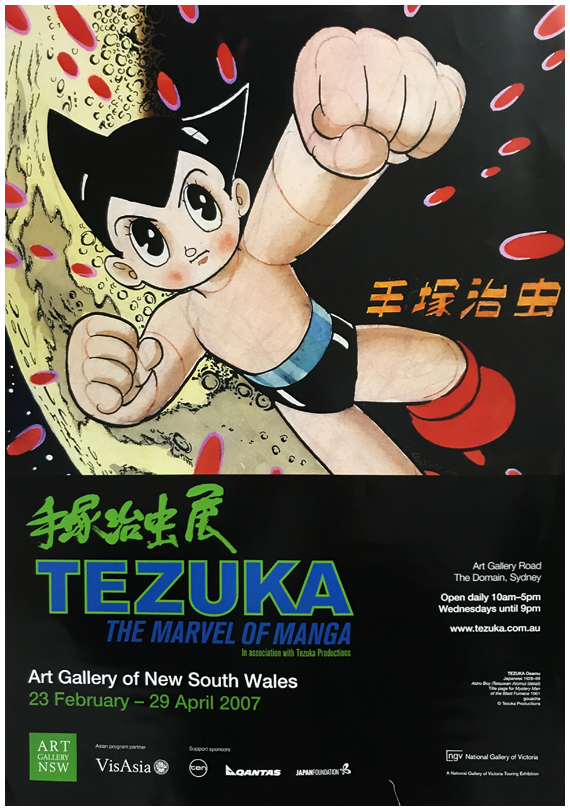

Tezuka: the Marvel of Manga is an exhibition curated by Philip Brophy, profiling the Postwar Japanese manga of Japan's leading and most historically important manga artist. The complexity, freshness and startling originality of Tezuka's oeuvre - rarely showcased outside of Japan - is highly relevant to the merging pan-Pacific exhibition options which Australia is well-placed to nurture and exploit. Originally conceived in 1997 after discussions with Tezuka Productions (following Philip's other curatorial projects: KABOOM! Explosive Animation from America & Japan and Osamu Tezuka - Glimpses of a Fantastic Imagination), the exhibition has since been developed for presentation and management through the National Gallery of Victoria.

A catalogue was produced for the exhibition. It contains 2 essays by Philip, plus first-time translations of 5 texts by Japanese historians and theorists on Tezuka's manga. A selection of Tezuka's own ruminations on his classic works is also translated into English for the first time. The catalogue is extensively illustrated and comes in a special padded cover with silver-foil lettering.

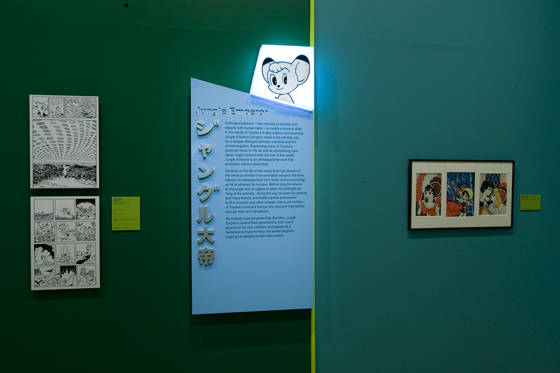

Installation view - National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne © 2006

Credits

Curator/book editor: Philip Brophy

National Gallery of Victoria staff: Tarragh Cunningham, Nicole Montiero, Cathy Leahy, Daryl West-Moore, Tony Elwood

Tezuka Productions staff: Takayuki Matsutani, Yoshihiro Shimizu & Mika Suzuki

International Co-Ordination, interpretation & book translation: Tetsuro Shimauchi

Assistant International Co-Ordination: Rosemary Dean

2007

Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney

Asian Art Museum of San Francisco

2006

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Installation view - National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne © 2006

Overview

Aims

The aims of Tezuka – The Marvel of Manga are to:

1. contextualize the relationship between manga and anime to illustrate how the latter grows from a long-standing tradition of the former

2. to site manga as part of Japan’s cultural and artistic pursuits in the realm of prints and drawing

3. to honour and posit Tezuka as the most important postwar artist in this field

Curatorial statement

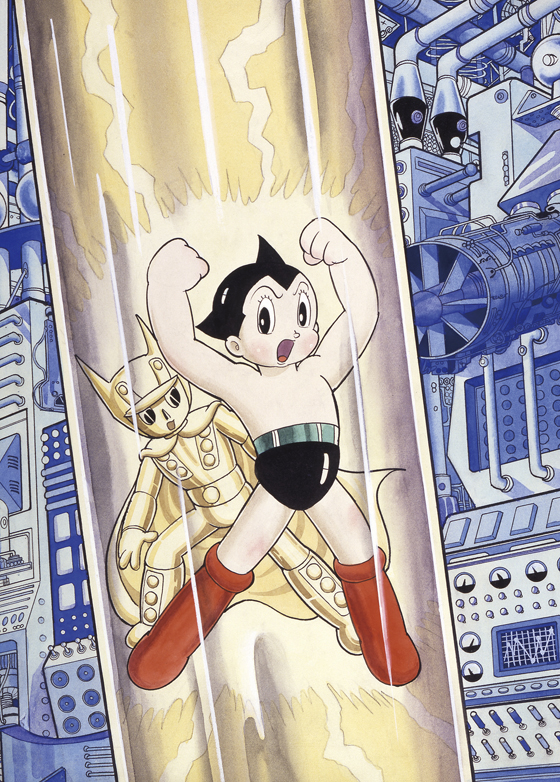

Perhaps the most accessible route to the fantastic world of Japan's greatest manga artist and animator Osamu Tezuka is through the angelic face of his pre-pubescent robot creation, Astro Boy. First aired in Japan in 1963 and redubbed in America in 1964, ASTRO BOY has since become not only a major postwar icon for Japan but also a strangely attractive post-baby-boomer figure in non-Oriental countries. The fact that many westerners presume Astro Boy to be American is an indication of how undervalued and ignored anime (Japanese animation) is within film history, as well as a sign of how readily an American dialogue-track can cast any production in the shadow of its accent.

The manga upon which ASTRO BOY is based - Tetsuwan Atom (Mighty Atom)- is one of Tezuka's most well-known works, serialized in phases from 1951 to 1968. It is a fascinating tale set in the 21st century, where superminiaturization of electronic components and advances in plastic applications for artificial skin have facilitated the design of extremely human-like robots. And where better to render similarities between robotics and genetics then in the highly-coded hieroglyphics of the manga page? Just as the manga form well suited such futuristic fantasy, so too did the idea appear molded by postwar Japan (the Showa 20s: 1945-54) when Japan was rebuilding itself psychologically and preparing itself for the electronics explosion of the 60s. ASTRO BOY in some measure can be viewed as a contemplative embodiment of this postwar period - a period of intense reflection that affected much world cinema.

Installation view - National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne © 2006

In the original ASTRO BOY manga, Professor Temma aspires to create a new wonder robot with the aid of extensive R&D by the Science Ministry. He names the robot after his recently deceased son, Tobio. But Professor Temma becomes disillusioned with the almost-perfect nature of the ageless boy-robot and in a rage sells him to a circus. There he is rescued by Professor Ochanomizu who educates Tobio and renames him Tetsuwan Atom. With new social skills, advanced robotics and a memory bank of human-affected experiences, Tetsuwan Atom commits himself to serving humans - but forever ponders his relationship with them. This is Pinocchio retold through Asimov, but with a molecular explosion of themes and dichotomies to do with the essence of soul, the imagination of children, the gender of plastic and the morality of cuteness. And despite the TV-reduced plots (Tezuka said they tended to be 'patternized') and an American woman's voice-over, the context, culture and form of the animated ASTRO BOY resonates with a peculiarly Japanese configuration of trans-gender postwar neo-human traits not usually explored by traditional social-conscience photo-cinema.

Tezuka happens to have been remarkably articulate about his manga and anime creations, particularly in terms of his themes and the ways in which they were acutely expressed through the formalism of his story-imaging and what he later termed a 'semiotics of manga': a signage system which could convey ascribed universals tied to a dramatic flow. His published texts include historical overviews (the POSTWAR HISTORY series of Gag, Sci-Fi and Girls comics); instructional manuals (HOW TO DRAW COMICS: FROM PORTRAITS TO COMIC STORIES) and autobiographical ruminations (I AM A CARTOONIST). Reinforcing his ideas, of course, are the actual works. The afore-mentioned themes of ASTRO BOY, for example, are crisscrossed like delicate webbing through the allegorical pasts and speculative futures of hundreds of manga he published, and in anime based on his manga and devised as original projects.

Installation view - National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne © 2006

Tezuka seriously drew manga from 1941, but such entertainment in wartime Japan was frowned on, so it was not until 1946 that he first received a publishing deal. By the mid-50s, Tezuka led the first manga boom in the children and young adult markets, inspiring many other artists and publishers to expand the field. Tezuka by then was recognized for shifting the blockage of manga visual formulae toward cinematic effects, and infusing his narratives with a range of emotions and tonalities which redefined notions of children's entertainment. Come 1977, Kodansha commenced publication of THE COMPLETE MANGA WORKS OF OSAMU TEZUKA which has grown to 400 hardbound volumes containing over 150,000 drawn pages. Prolific, imaginative and driven, Tezuka also wrote, directed and produced animations from 1962 up to his death in 1989: a total of 14 TV series; 36 shorts and TV specials; and 23 feature-length titles. Regarded in Japan as an artistic sensei (master) and a figurehead for the manga and anime industries, his legacy is kept alive by the Osamu Tezuka Manga Museum in Takarazuka, and by the continual trickling of his work into the west.

Taking into account (a) cultural gaps between Australia and Japan; (b) the problematic way the cultured-West generally views comics and cartoons; (c) the paucity of translated manga and anime from the world's largest producer of comics and cartoons; and (d) the imposing bulk of material Tezuka produced - The Marvel of Manga is but a slight nudge to entice gallery and film patrons in Australia to consider the trans-global issues raised by the powerful post-nuclear sentiments and ideas contained in Tezuka's seemingly-cute animations. Familiar yet strange; European yet Asian; kitsch yet elegant; iconic yet distinctive - Osamu Tezuka's manga and anime affords the interested viewer an insight into the perplexing formal mutations and weird narrative contortions which typify postwar Japanese culture and define Tezuka's own fantastic world.

Installation view - National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne © 2006

Technical

Structure

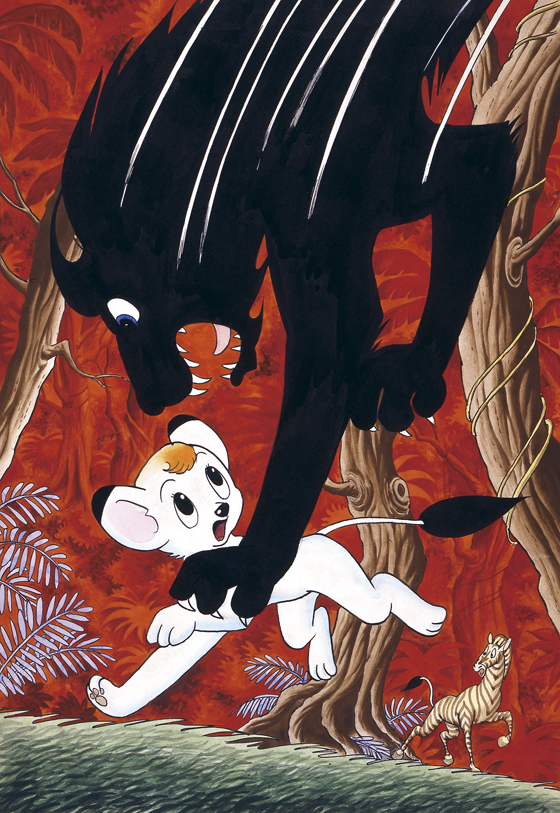

The exhibition is concentrated on 2 distinct bodies of work:

TV/film manga

Metropolis (Metoroporisu)

Astro Boy (Tetsuwan Atomu)

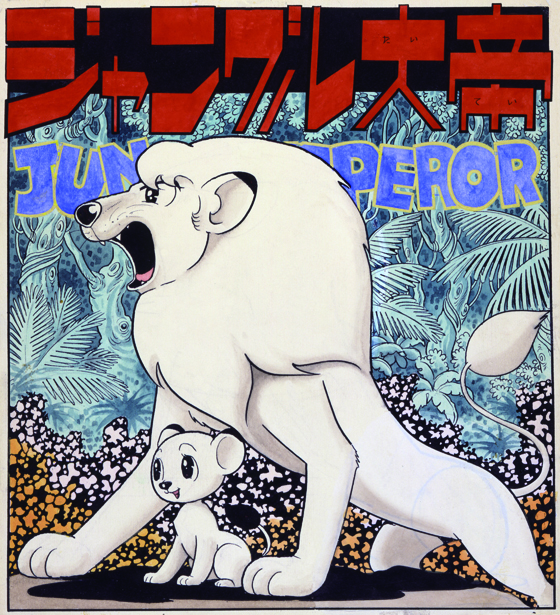

Jungle Emperor - aka Kimba The White Lion (Jungeru taitei)

Princess Knight (Ribbon no kishi)

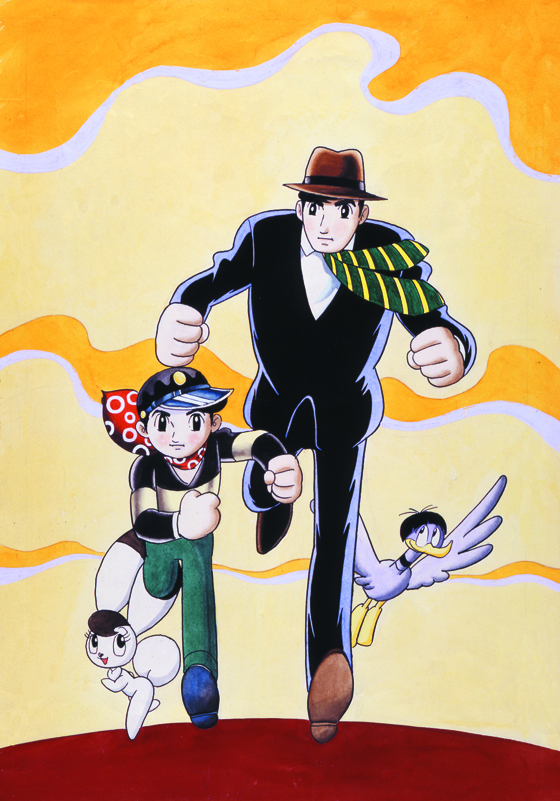

Wonder 3 - aka The Amazing Three (W3 aka Wunda 3)

Marvelous Melmo (Fushigi na Merumo aka Mamaa chan)

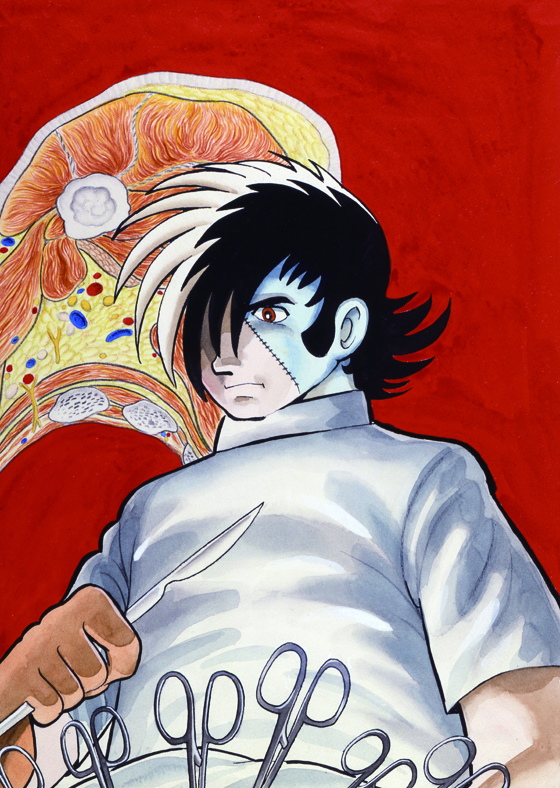

Black Jack (Burakku Jakku)

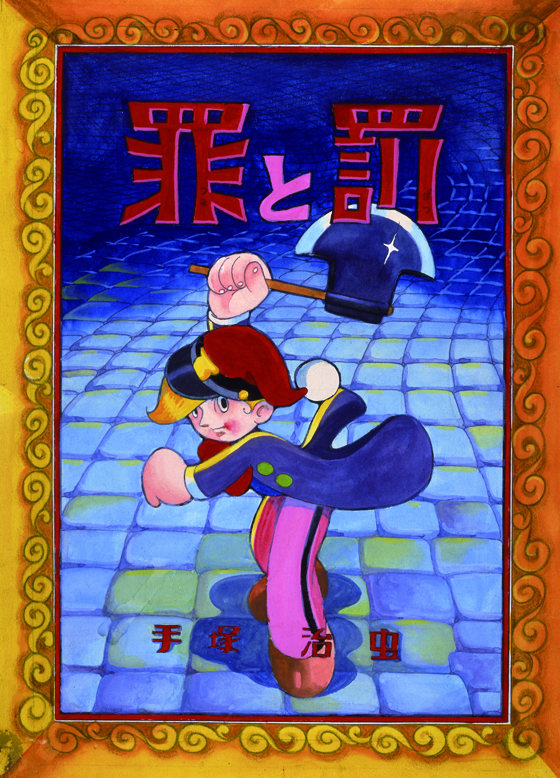

Gekiga (drama pictures) manga

Crime & Punishment (Tsumi to batsu)

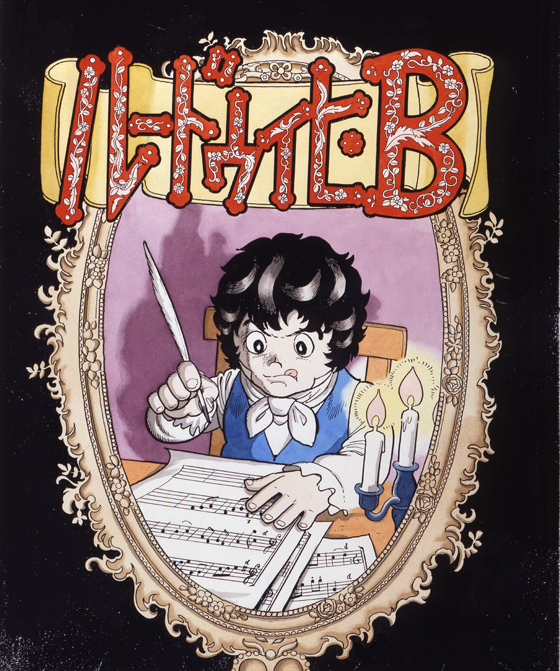

Ludwig B (Rudovihi B)

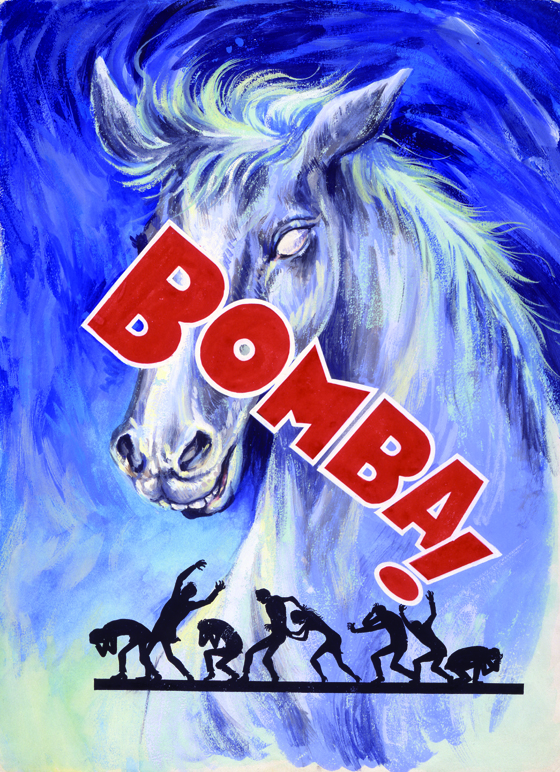

Bomba! (Bonba!)

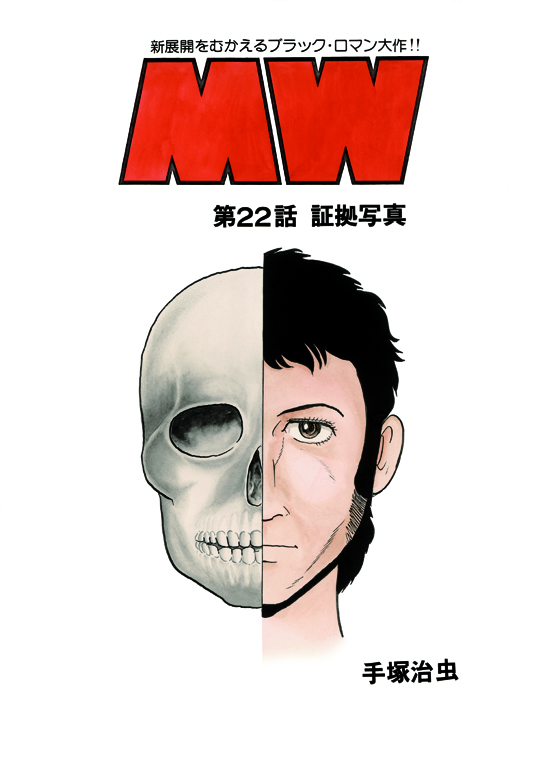

MW (Mou aka MW)

Eulogy for Kirihito (Kirihito sanka)

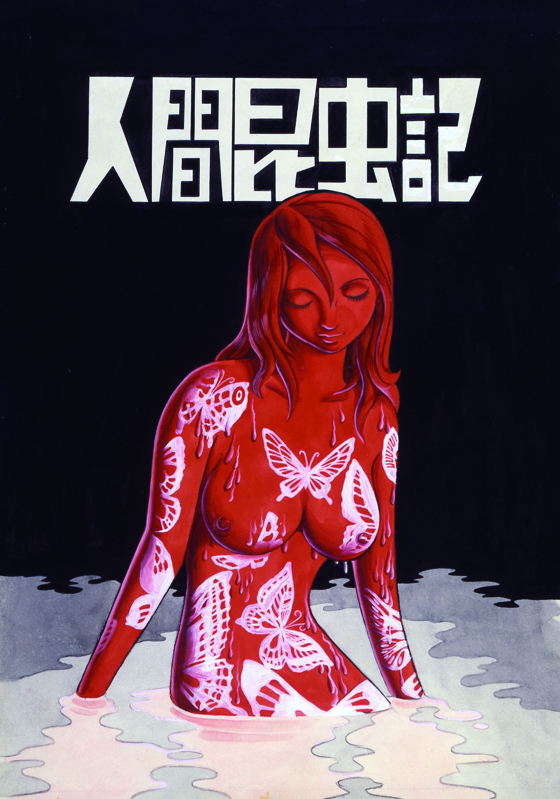

Human Metamorphosis (Ningen konchu ki)

Song of Apollo (Apporo no uta)

Buddha (Buddha)

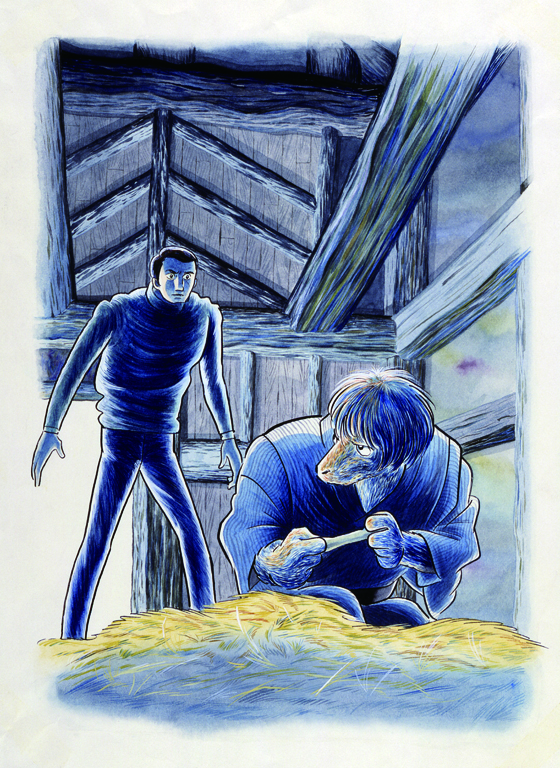

Phoenix (Hi no tori)

Exhibition

Contents

1. Original pencil and ink drawings on paper (marked up ready for plate-making in preparation for the printing of the manga)

2. Original water colours on paper (actual size and larger scale works used for the printing of colour covers and title pages of the manga)

3. Blown-up digital print reproductions of manga pages

Design

The exhibition is designed to give a sense of the viewer entering into the world of the manga pages. The arrangement is based on chapter titles - large plywood panels with 3-D lettering and an illuminated lightbox display of a manga character - and pages - the sequencing of framed original pages. The 'chapter title' display gives some background on the manga, while each sequence of framed original pages is accompanied by a small didactic panel which summarizes the dramatic action depicted. Nearly all pages in the exhibition (a total of 234) have no written dialogue or exposition, allowing the viewer to freely connect to Tezuka's artistry in using sequenced images to convey dramatic momentum. The colour coding of the walls is to generate a subliminal sense of changing from one manga to another, as the viewer moves through the space.

Installation views - National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne © 2006

Mini promotional car - National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne © 2006

Freeway sign - National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne © 2006

Freeway sign - National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne © 2006

Exterior banners - Asian Art Museum of San Francisco © 2007

Exterior banners - Asian Art Museum of San Francisco © 2007

Interior banners - Asian Art Museum of San Francisco © 2007

Interior banners - Asian Art Museum of San Francisco © 2007