Techno Collapse

Techno Collapse

Sound in the Age of Mechanical Malfunction

published in Like No.15, Sound Art special issues, Melbourne, 2003Influidity of sound in Fluxus

There is something undying about Fluxus. A longstanding haven for artists to use sound as a platform for their ponderous ruminations on how to stage conceptual strategies within the exploded paradigms of the postwar gallery, Fluxus flaunts sound as an imaginary space wherein one can fantasize an escape from music. With its neo-dada and pre-yippy anarchism, Fluxus toyed with ‘the beyond’ as a conceptual utopia wherein one could hear symphonies in shortwave radio static, musicality in chalk scraping, and virtuosity in hack-sawing. Today still, art students thrill to this para-transcendental feature of Fluxus flights of whimsy, looking at blurred action photos of be-suited men from the 60s engaged in maniacal acts with pianos, violins and sheet music, imagining how thrilling it must have ‘sounded’. Today still, Fluxus is a reservoir of signage; of gestural statements which enact conceptual ‘soundings’.

As conceptual art, there is much that fascinates in the museographic interpolations of the Fluxus compendium. Yet there has always been something remarkably ‘unsonic’ in Fluxus’ collective excursions, protrusions and bachannales. While Cage’s recorded works still test the limits of experiential phonology (perplexing one as to how one ‘listens’ to the recorded ‘thing’ which is but an occurrence in a wider sonic realm of existence), the bad live audio of most historical Fluxus events is material proof of the events’ primacy as action/gesture to which sound was always subordinate. (The live Fluxus events I have attended over many years have been worse.) If Cage replaced his brain with one big throbbing ear, Fluxus members – despite their kinship with Cage – replaced their ears with two miniature brains. The result has been and remains a trail of perceptually shallow sono-musical artifacts: dry, lumpen and influid. While Cage often waxed lyrically about the act of listening, it remains that there is anti-music and there is anti-music. Some of it – like Cage’s Fontana Mix (1958) sounds awesomely post-musical; some of it is as interesting as listening to the sound of a computer keyboard typing out an artist’s statement. (And no: that isn’t meant to be a smartarse conceptual piece on my part – although it could be a Fluxus piece.) Ultimately, Fluxus is but a museographic recording of the outside world. It was only rare figures in Fluxus like Cage who ushered ‘the outside’ into the auditorium, into the radiophonic apparatus, and into the compositional process. Fluxus theatricalized this desire without realizing the cultural space of their gestures, and in doing so generated acultural art and asonic sound.

The modernist will to destruction

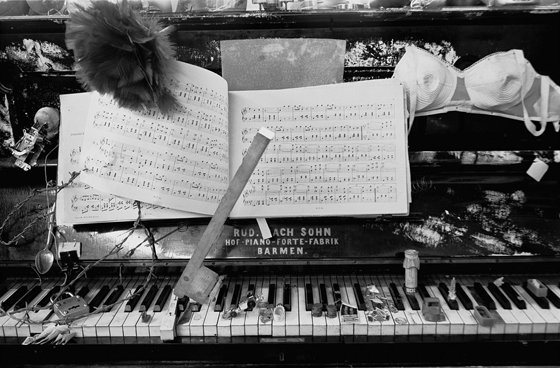

The sonic emptiness in the sound of most Fluxus work is not surprising. Just as the formal genealogy of video art grew with vulgarity from the residue of bad sculptors who knew naught of the electronic media, the narrative morphology of Fluxus sprouted from the bemused esoteric ramblings of bad poets who knew less about sound. It is in this soaked ground of poetry that Fluxus takes seed, clinging to a hallmark of modernist poetics: the expression of beauty in violence and the aesthetics of destruction. Be it ethical moaning about being stricken with an ‘awareness’ of this, or the self-centred wallowing on the ejaculatory throb inherent in ‘critiquing power’, modernist poetics love crises and catastrophes as much as the romantics jerked off to sunsets and sunflowers. Superficially, Fluxus appears to move past this. It doesn’t. Fluxus is comprised of the same molecular grain of destructiveness which anxiously leavens both existentialism and expressionism. With its matrix of shattered violas, doused microphones, upturned pianos, decimated music boxes, degraded tape-recorders, enflamed vinyl records and chainsawed record players, Fluxus provides but one of many incendiary dots along the historical fuse which links Tchaikovsky’s cannon fire in The 1812 Overture (1812) to Jimi Hendrix’s detonation of The Star Spangled Banner (1970).

Might I be wrong here? Maybe Fluxus is not about destruction. Right: and maybe the Futurists really just needed a good hug to make them feel better about life. It is hard to not see the orgies of formal violence and gestural decimation which pepper visual modernism with slashes, splashes, splays and spurts as symptomatic of a particular type of action-statement in mark-making which 20th Century music composition and performance generally avoided. Following this logic, it is to be expected that of all the wondrous works created by the pantheon of the orchestral avant-garde (Ives, Partch, Stravinsky, Schoenberg, Varese, Bartok, Ligeti, Crumb, Messiaen, Penderecki, et al – most of whom, it must be noted, Cage critiqued in one way or another), the Fluxus movement and its preoccupation of ‘action as art’ is perceived so relevant to the gallery and so antithetical to the concert hall. But in all its radical gesturing, the ‘reactionary actionism’ of Fluxus is integrally tied to the musical Academy as a binary inverse of that institution’s power: Fluxus’ most potent statements need that damned grand piano in order to destroy it. Again and again and again. “Who destroys the piano these days?” Only Fluxus.

The romantic championing of Fluxus’ innate chauvinism – its withered penile wit, its yawning pranksterism, its bargain-price rebellion – is typical of the support given to all transgressive art moves which mold the body of modernism as a heroic vessel for the valiant projections of ‘ground-breakers’, ‘barrier-crossers’ and ‘envelope-pushers’ (note those hymen-rupturing terms). Like so many modernist movements and their intersticed homages, Fluxus betrays the same boys’ club sentimentality which revels in the supposed liberation unleashed by what in many cases is grown men behaving like children. And just as how any school yard will create a fictive power space for nerds, dags, weirdos and oddballs to congregate and share their inadequacies, Fluxus replicates the same arena of therapy: part global-baptism, part international networking, part transcultural essentialism. A tincture of Zen, a daub of Futurism, a hair from Hemingway’s stubble, a drop of sweat from the brow of Duchamp playing chess, a faint memory of having once heard a radio somewhere, and the warm woodgrain of a cello once held between the thighs of an upper middle-class virgin. Mix it all up and spatter it across the gallery like a fecal expulsion of your renouncement of the conservatism of the art establishment and pop culture. Exhaustively document it and pathologically fawn over your little scribbles, wax droppings and crayon smudges like an overwhelmed fetishist. Claim renewal, rebirth, rejuvenation. Be Fluxus.

Those who are deaf to noise

Fluxus undoubtedly enjoyed a cathartic, tantalizing moment in its rebuttal of the musical Academy and its ossification of the fuller potentiality of sound. In doing so, they promoted a ‘sono-gesturalism’ in place of the musical gesturalism which had become the authorial trait of compositional practice in the first half of that century. But 20th Century music – incorporating the redefinition of music for that century – did not need Fluxus as either comrade or enemy. Nor, I would argue, has it required Fluxus’ hyper-personal diaristic drivel to articulate that redefinition of music into the collapsed territorial shifts of ‘sound’. Yet it remains that Fluxus is cited within art theory more than any other phase of 20th Century music as a prime mobilizer in conceptualizing a cultural breaking of the sound barrier. Those who cite Fluxus in this way, it should be noted, are usually deaf and dumb when it comes to sonic literacy. Picking up on the poetic rhetoric of Fluxus-speak and being unable to discern the lack of phenomenological aura of Fluxus-work is to be expected by curators, writers and artists in the visual fields. Less acceptable is how Fluxus – along with many sound theorists from John Cage to Brian Eno to R. Murray Shaffer – have been taken at the value of their words more than their actions, artifacts or analyses. That is, their ideas – ranging from the inspired to the insipid – have been acknowledged without locating them within the most basic of cultural contexts. Fluxus quips about ‘noise’ can illuminate only if one presumes that forms like cinema, musique concrete, rockabilly, bubble-gum, heavy metal, techno and glitch have not made a single mark on the planet.

The Art of Noise – a British studio project instigated by pop music producer Trevor Horn in 1983 – released their second single Close (To The Edit) (1984) with a video clip featuring a very young girl directing three big oafs to totally destroy a grand piano. Having no vocals save for the odd non-sequitur sample, the clip is edited to the onslaught of programmed beats, transforming it into a synchronized symphony of destruction as the three terrors plane-saw, chainsaw and jack-hammer the piano to shreds. What with a sample of a car engine ignition and rev comprising the central melody, the song and clip form a canny and direct encapsulation of the popular history of noise: from Luigi Russolo’s anti-piano manifesto The Art of Noises (1913) to John Cage’s invention of ‘the prepared piano’ (1938) to the Fluxus group’s destruction of the piano in events like Philip Corner’s Piano Activities (1962). Spread throughout this sono-musical cultural debris is a grime fertilized by those art trajectories – namely, an overlaid history of record production invoking the sonic experimentation of Ennio Morricone, Joe Meek, Esquivel, Burt Bacharach, Brian Wilson, Phil Spector, Lee Perry, Jimmy Page, Mike Leander, et al. Tacky, silly, obvious, cynical, self-conscious, overloaded, transitory, ephemeral – Close (To The Edit) is a good example of the culture of noise and sound which intersects pop music far more profoundly than the cult of miniature wooden boxes and artily scrawled music manuscripts which are still preciously executed in the name of Fluxus.

In its grandiose cartoon of the grand piano attack, The Art of Noise provide one of many examples of the celebratory absurdism which accepts the destructive impulse in modernism as a given, a granted, a gone argument. No big point; no great revelation; no critical recourse. Art-as-destruction and destruction-as-art are important tropes still in contemporary art and culture, and notions of destruction in 20th Century music – more so than any of the visual arts – withholds great phenomenal complexity which has been more vibrantly filtered into pop music than it has been dialectically extended by the more respected realms of inquiry promoted by Fluxus, sound art or acoustic ecology. In the truly expanded realm of the sonic (and that means everything from taped prayer calls in Istanbul to Toru Takemitsu’s score for Onimaru to Metallica in concert to Pauline Oliveros underground) the ancient, mythical and classical symmetry of the creation/destruction binary flickers like a thin conceptual flame. For sound is the collapse of energy into itself: its life is a biorhythmic feedback of its own generation, dispersion and reflection. It cannot be destroyed and as such it is more powerful than all the objects of its destruction. The bulk of what has been labelled ‘noise’ throughout the 20th Century – either as hateful damnation or gestural embrace – is quite simply an admission to an inability to listen.

Sound as destructive creation

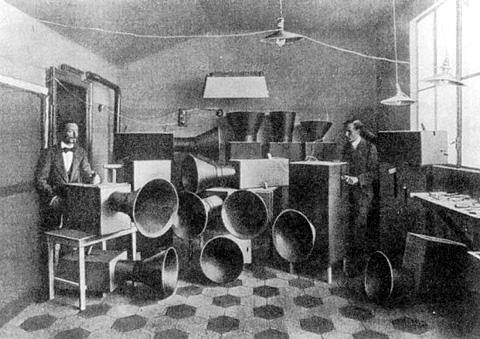

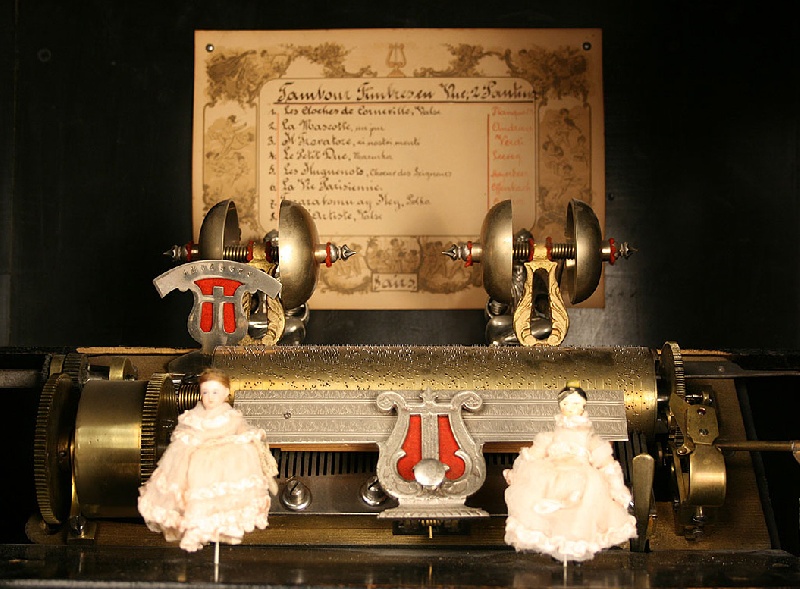

There is something undying about destruction. Luigi Russolo’s intonarumori or ‘noise machines’ – beloved by visual artists mainly because of the quaint photographs of him surrounded by these strangely formal black-box contraptions – have never really been acknowledged in relation to their sono-cultural acoustic environment. At the turn of the 19th Century, one of the major forms of pre-designed musical consumption was ‘music boxes’: those tinkling mechanisms often hidden in small personal valises, fob watches or charm necklaces, where the act of opening them triggered a wound-up spiked metal cylinder to prick a series of tiny tuned metal prongs. Sounding like a miniature celeste, their delicate ‘tinkerbell’ tones would sail forth, and for centuries prior had been linked to the intimate, the feminine, the magical. Russolo’s response to the barrage of tinkles which beautified, sedated and entranced the modern world at the fin de scile was to aggressively employ the same principles in the form of grossly enlarged, untuned, hollow, bass-heavy boom-boxes, inside which a hand-cranked shaft connected to brutish cogs which caused harsh and violent clickity-clacking. Running at high speeds, the reverberant sound of the gnashing wooden teeth generated the timbre of a horrific mutation between a cello, an swizzle stick and an organ grinder. A typically macho-Euro gesture, the same cock-throbbing noise is to be found in gabba techno and happy hardcore pumping out of V-8 engines burning rubber at traffic lights in the outer burbs. The intonarumori of Futurism has never left us.

When considering the relations between the pithily conceived binary of creation/destruction in the age of mechanical reproduction of the sonic, key factors should not be ignored:

1. All technology is destructive through its amplification of scale, its shift into virtuality, and its bodily replacement.

2. All action is sexual due to its predication on force through pressure and the establishment of the active event.

3. All sound is violence due to the manifestation of sound waves, their displacement of space, and their rupturing transformation of atmospheric density.

Russolo’s intonarumori – like so many inventions and applications of ‘sonica’ – destroy through acts of creation and create through acts of destruction. As generators of extant, actual and visceral energy (ie. sound heard by you in a space as opposed to an image stored by you in your mind), they affirm the surface of the sound world as a skin whose molecular decimation is the granularity of its existence. While the Futurists can to a degree be stereotyped as rev heads who welcomed the machinic into the operatic, their legacy as ‘noise addicts’ is a major governing factor in the sonic age of mechanical reproduction and all the attendant sonic detritus which to this day still accrues from their original shock waves. Most importantly, it is upon hearing Russolo’s intonarumori (first recorded in 1977 by the Historical Contemporary Art Archive of the Venice Biennale) that the precise nature of their granularity makes sense. One can feel those chattering teeth eating into the boxes’ mechanisms: these are self-destructing machines, and in contradistinction to their ‘futurist’ impulse, they prophetically forecast an age of mechanical malfunction.

The act of recording

A thin line separates reproduction from malfunction because all media encoding/recording requires the destruction of the very media which beholds its content, information, and data. From hole-punched paper scrolls to wax cylinders and rolls to shellac and vinyl discs to magnetic tape spools to digitized laser discs, audio data digs into the calm sea of media surface, rupturing that surface through a destructive scrawl. The notion of ‘surface noise’ – which people still foolishly believe has been eradicated by digital media – has been as present in the 21st Century as much as ink has seeped into paper for centuries before. It is therefore typical and expected – rather than reflexive or revelatory – that modernist sound art practices have heightened ‘surface noise’ as an attempt to empty media of content and make contact with its innate and abstract materiality. While classical arguments on the ontology of objects centered on form/content debates (how do you separate the two, when does one become the other, etc.) modernist and postmodernist arguments on the ontology of media is refocused at the micro-molecular plane of acts, actions and actualities of recording. Like the lunar surface of our skin and the wild forest of our scalp, the recorded surface is revealed to be a complex field of irregular undulations and ungainly indentations. Across its scarred, scrawled and scratched terrain, there can be no separation between the surface and its disturbance; the skin and its scaling; the bed and its x. Thus, nothing is either created or destroyed in the act of recording: sound just materializes, for sound is the relation between materials and the connections between surfaces. Sound is material.

Zoomed-out from the micro-detail which defines and determines the specifics and nuances of any medium’s ‘sound’, the materialization of sound does leave its mark on the human. The deaf and dumb society of ‘hearers’ (that includes most ‘visual artists’) fortunately possess hyper-sensitive eardrums which respond to the sophisticated aural and acoustic manifestations of those micro-markings irrespective of the hearers’ consciousness of the event taking place. One does not need to be a devotee of Cage to experience the miniaturized whine of a mosquito close to your ear at 3am. Nor does one need to have read Russolo to experience the subsonic wrack of a train passing overhead as you stand underneath its bridge. From the ringing of our frontal lobes to the quaking of our pelvic bones, our physical being is itself a recording device whose materiality is as much defined by sound as it is by atmosphere, pressure and gravity. We have scant cognitive understanding of the bulk of its operations. It is neither mystical nor metaphorical to state that we can feel these phenomenae in the material sense.

Guts, glitches and ghosts

It is this abject physicality of sound which is often forgotten in the rush to make lofty and revolutionary claims for the sonic by sound artists, acoustic ecologists, musical therapists and aural architects. And it is the same abject physicality which is transforming the social manifestation of sound to such an extent that we may be in the midst of an inversion of the ‘psychoacoustic’ (an understanding of how the mind perceives sound) into the ‘physioacoustic’: an understanding of how ‘the body perceives sound’. It must be remembered that the advent of phonology at the start of the 20th Century exploded the societal ear with a previously unimagined experience: the active reduction, subtraction and modulation of frequencies from their original acoustic source. In other words, people were hearing for the first time a ‘non-manifestation’ of the previously accepted reality of, say, the sound of a voice, violin or piano. Early cylinder recordings back then would have appeared as ‘unreal’ as the simulation of a Hawaiian guitar on a Lowry organ appears to us now. Today, we are bombarded with a gloriously glutted excess of attempts to trigger the body as whole or fragment – from the guttural swell of Jeff Mills ‘apparition’ of bass which transforms our skeleton into an aqueous shudder to the diffused ‘indirection’ of 2k mobile phone tingles which transform our temples into roaming mechanisms.

A significant consequence of the digital era is the totally unironic return to the same ‘physioacoustic’ sensation of experiencing reduced frequency bandwidths in forms and manners entirely reminiscent of 19th Century fin de scile recording devices. While bass frequencies affect the body’s totality – its bulk, mass, constitution – treble frequencies synaptically ensnare our attention. A low rumble can be subsumed into the background ambience of our everyday noise floor, but high-pitched beeps function as harsh ruptures and irritating incisions into the acoustic continuum of our surroundings. If anything, high-end frequencies dominate more than ever before, irrespective of any issues of fidelity, mimeticism or veracity. Consider:

1. the film soundtrack’s privilege of the tinny human voice above all other background atmospheres and frontal effects

2. the telephone’s broadcast of funneled frequencies of the human voice directly into the ear cavity

3. the lo-bit incorporation of tonal data into digital alarm clocks and computer beeps designed to rupture the eardrum with harshly inorganic waveforms

4. the acceptance of lo-res corruption in the presentation of audio data on websites, CDRs and games in order to hierarchically displace the material with significant visual/motion/interactive data

5. the hi-end fidelity of digital recordings, hi-tech studio samples and FM-synthesis simulations as an overload of waveform data for the erotic aural massaging of the ear

6. the trend of ‘glitch’ music as an enrapt collision between rarefied experiments in 70s electro-acoustic music and prosaic and mundane malfunction in digital technologies.

The sonic - by virtue of its potential to signify and iconicise – remains molecularly locked in a bind of hypermateriality and abject connotation; between the stinging aural sensation of hearing that tone, beep, or glitch and the way in which that sound can be used to communicate everything from “you’ve left your dishwasher door open” to “your insulin levels are too high” to “I am the art of noise”. All manner of encoding and decoding enacts a shuttle between these two states, and provides further substance to the argument that there is no such thing as noise – anywhere, in any situation, or on any surface.

While The Art of Noise’s Beat Box Diversion 2 aptly signified the pop cultural dawn of sonic simulation in the realm of the musical, Oval’s Systemische (1996) similarly signified the pop cultural dawn of sonic malfunction in the realm of the digital. To this day, it stands as a charming erotica of timbrel corruption. But to this day, nothing has bettered the numerous times I have been in a noisy restaurant and a Gypsy Kings’ CD has jammed into millisecond sample-looping and transformed the environs into a warzone which sonically hammers the customers to the extent that I had been numbed by the Gyspy Kings’ folksy froth. Recalling the late 80s’ grrl pop-noise group with possibly the best name ever for a band – We’ve Got A Fuzzbox And We’re Gonna Use It – most supposedly cutting-edge ‘glitch artists’ and ‘laptop musicians’ should be collectively called We’ve Got A Plug-In And We’re Gonna Use It. For the power of glitch is not in the produce of artists – despite the majesty that rock/pop acts like Oval, Pole, Flanger, FX-Randomize, Farmer’s Manual, Matmos, et al, convey in their compositions, and despite the sci-fi pants-wetting which afflicts so many digitalists. (Remember: it only took 3 years for a track from Oval’s Systemische to be used to advertise Calvin Klein’s Eternity on television.) No – sound artists of any persuasion do not possess such power. The power of glitch lies in its exposure of the act of digitizing as a hypermaterial consequence of its place in a long lineage of mechanical malfunction.

Text © Philip Brophy. Images © respective copyright holders.