The Birds

The Birds

The Triumph of Noise Over Music

published in Essays In Sound No.4, Sydney, 1999Establishing subjective sound through electronic treatment

The opening sequence to THE BIRDS serves as an entry to the non-musical, solely-sonic domain of its soundtrack. High contrast visual abstractions of birds move across the frame, half-photographed, half-animated (Ub Iwerks - veteran cartoon director/producer - served as special photographic consultant on the film). Simultaneously, squeals and squawks attack the viewer's ears. These sounds have a birdlike quality about them, but it soon becomes apparent that the sounds are more alien than avian, more artificial than natural.

Produced by electronic music composers Remmi Gassman & Oskar Sala, the processing of the sounds utilizes many stylistic traits established in the field of musique concrete. In this case, taped sounds of birds are altered in pitch, tone, duration and shape, then mixed into a multi-layered cacophony of screeches and flapping sounds in sync with the animated silhouettes of bird shapes. Having been cued to read a mimetic representation of 'birds' with the title THE BIRDS, we are jettisoned into experiencing a sensation of 'birdness'.

Does this difference between 'birds' and 'birdness' signify anything? In a story about birds whose behaviour defies ornithological precepts, the very concept of a bird comes into question. Thematically we can accept the birds' presence and actions as symbolic of an inexplicable terror, but only if a collapse of everything that defines a bird is visually and aurally apparent on the screen. We should hear and see birds while acknowledging that they are not like normal birds. The key solution provided by THE BIRDS lies in presenting the birds from both objective and subjective viewpoints - identifying 'birds' (photographed/depicted/wrangled) versus sensing 'birdness' (animated/suggested/matted).

The title sequence is a distillation of the subjective impression of birds - of being caught by a flock of them as they swoop around you, pushing envelopes of air against your ear drums and flitting within your peripheral vision. You are not watching birds: you are being attacked by them. You are more aware of their presence - sonically and visually - than you are able to objectively hear and see them. Other factors come into play. Formally, here is a title sequence devoid of music and hence absent of the emotional cues and stylistic cards conventionally employed to situate the viewer/auditor in a specific frame of mind. Technically, the frequencies of the sounds are harsh, sharply resonant and redolent with clashing tones. No sweet trills and warbling melodies here (in part due to atonal composer Bernard Herrman operating as sound consultant for the film). Combined, the subjective viewpoint of attacking birds, the unconventional title sequence and the technical aural aspects psychologically work on the viewer/auditor to unnerve and unsettle: these birds are after you.

The title sequence fades to black as the bird noises reach a reverberant crescendo. This cross-fades with an unstylized sound of massed birds as the image of a flock circling over San Francisco's business district fades up on the screen. Car traffic and tram bells mingle with the birds in long shot, replacing the abstract/stylized/artificial sonorum of the title sequence with what one presumes will be the representational/realistic/natural make-up of the depicted fiction. Yet this simple cross-fade - this slight-of-hand in the momentary black pause - perversely forecasts the collapse between objective illustration and subjective impression which will shape the film. At points the sounds of birds will be the symbolic conveyance of invisible terror; at moments their silence will mark their deathly presence. In short, all modes of audio-visual depiction exude dread as they carry the potential to be diametrically inverted. This is nothing short of a 'terror of illusion' - a specifically audio-visual illusion - central to THE BIRDS' psychological horror.

Psychological & scopic manipulation through noise and silence

The psycho-acoustic manipulations which characterize the narrative purpose of THE BIRDS come into play immediately. The first scene set in the bird shop is a remarkably long one where slight plot and character information is imparted. Melanie (Tippi Hedren) orders a bird; she meets and plays a game on Mitch (Rod Taylor); he uncovers her pose as a saleslady; after a heated exchange she decides to buy him the birds he was after. This in itself appears to be a studied and drawn out tease typical of director Alfred Hitchock's approach: submitting trivial information to distract from you from the true mechanisms of the story. Throughout this scene - one of many banal, domestic exchanges - a wall of bird noise blankets all dialogue, forcing the audience to selectively mask out the high frequency information of bird noise from the mid-range tones of the actors' voices. While one can readily perform this complex perceptual manoeuvre in reality, many films will selectively reduce the volume of background noise to privilege on-screen dialogue. The fact that THE BIRDS refrains from this indicates that the noise level is deliberately maintained to build auditory stress within the viewer as a means of destabilization. You are subtly yet fundamentally being introduced to the unsettled psychological state which will eventually befall all the characters of the film as they are terrorized by bird noise.

In contrast, the ensuing scene deploys unnerving passages of silence. When Melanie delivers the love birds to Mitch's apartment, the scene's exposition is disarming in its lack of spatio-temporal ellipses. Melanie enters the building, catches a lift and walks down a corridor, closely observed by a resident. A strange voyeuristic effect is distilled through his silent, pernicious monitoring of her every move as she carries the love birds in a cage. As he scrutinizes her, we move with him in a tracking vacuum through the hotel's interior spaces. The plot remains immobile and silent, progressing nowhere and telling nothing. Just as bird noise has already been subliminally ear-marked to trigger anxiety whenever it recurs, so is extended silence now signposted as an aural appendage to telescoped viewpoints. A lack of sound will mean mean someone (or something) is watching.

Who/what is watching Melanie when she drives up to Bodago Bay in a string of plot-less wide-shots? Hard cuts between loud and soft engine drones transpose us into the car, the bird cage, then back out to the undulating landscape. Perversely, we have been granted visual information (she rides in the car with the birds) only to be split away from it, thereby inducing a desire to be thrust back into the action. Like all voyeuristic vantage points - the hill top, the key hole, the binocular glasses - frustration wells from seeing but not being there. Phenomenologically, one experience's sight at the expense of sound. Melanie's drive to Bodega Bay is an archetypal cinematic reconstruction of this crucial aspect of the voyeuristic effect, one that binds us, the film itself, and the birds. Only all three are capable of such telescoped viewpoints, and all three are perversely ensnared by the THE BIRDS' empty silence.

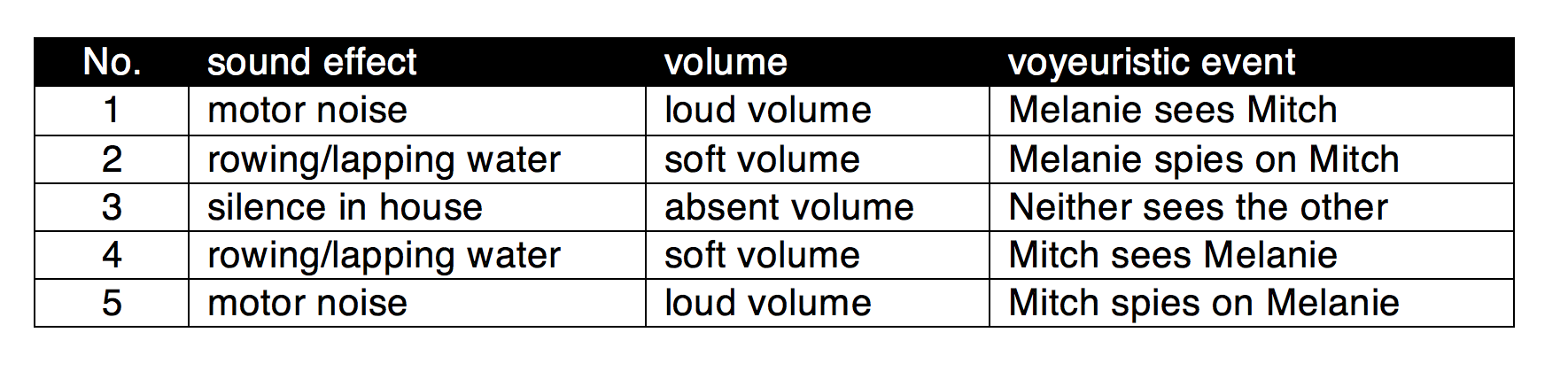

When Melanie hires a boat to cross the lake and surprise Mitch's sister with the lovebirds, a highly choreographed staging of voyeurism unfolds which formally melds audio-visual symmetry with spatio-temporal symmetry. Corresponding shifts in fields of vision and acoustic space occur as Melanie carries out her task:

With droll expectancy, the scene plays itself out, threading our voyeuristic pleasure into the game played by Melanie and Mitch. The major narrative purpose, though, is to rupture this dome of interaction with an inexplicable and unexpected force: the peck on Melanie's head by the seagull, sonically generated as a percussive incision into the sustained passages of sound and silence. This is the third governing effect of sound in THE BIRDS - the sudden interruption of any low-key ambience with a violent pneumonic event. Once quiet builds, noise will collapse it.

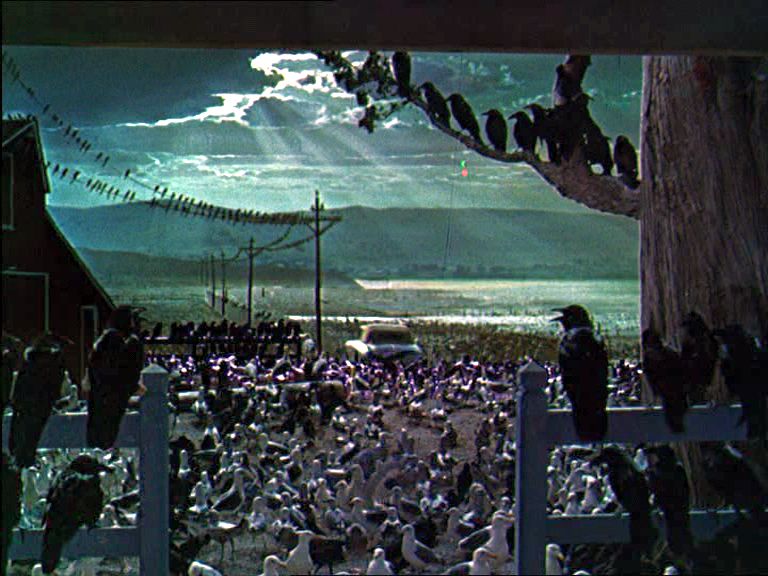

The voyeuristic configuration of us/the-film/the birds peaks at the climactic gas station explosion, helplessly witnessed by Melanie, Mitch and other diner patrons. The scene's perspective shifts with the advent of the explosion, transporting us to an ariel perspective - literally, a bird's eye view. The microscopic melee below - a mere scar of flame and smoke on the landscape - emits a thin trail of screams, lifted and dispersed by the hollow sound of upward spiralling winds. Who is watching here? On cue to the questioning of this shot, floating birds creep into the frame from all sides, gently hovering and letting loose occasional disinterested squawks. These visually matted birds are those same birds from the title sequence. Again, they terrorize the frame they transgress: they artificially inhabit the illusionary realm of the cine-photo frame, and their voice conveys a similar disjuncture between normal and aberrant sound effects. Again, we are made complicit with the actions of the birds by enjoying an avian sensory perspective of telescopic vision and displaced wind strewn acoustics. Again, the poetics of an emptied sound field haunted only by slight wind instil the scene with pregnant yet unspecified dread.

Absent music & the amoralizing of drama

There is much that is pregnant in THE BIRDS due to a distribution of radical imbalances between the audio and image tracks. The highest degree of this is to be found in the absence of music. Save for a piano, a radio and some children singing (all which occur within the visual diegesis) there is not a single note of orchestrated music sounded for the film's duration.

The soundtrack of THE BIRDS is literally that: voices, sounds, atmospheres. No violins. It rejects all musical coding traditionally employed to inform us of how we should care/think/feel/project at any point in the film. The absence of music is a specific 'sound of silence' which greatly enhances the THE BIRDS' peculiarly perverse dramatic tone. Picture one of many silent Melanies: locked into a seductive gravitational sway with her birds as she navigates the winding road up to Bodega Bay. She resembles an entranced conductor orchestrating her droning car engine. No purpose. No reason. No emotion. No music.

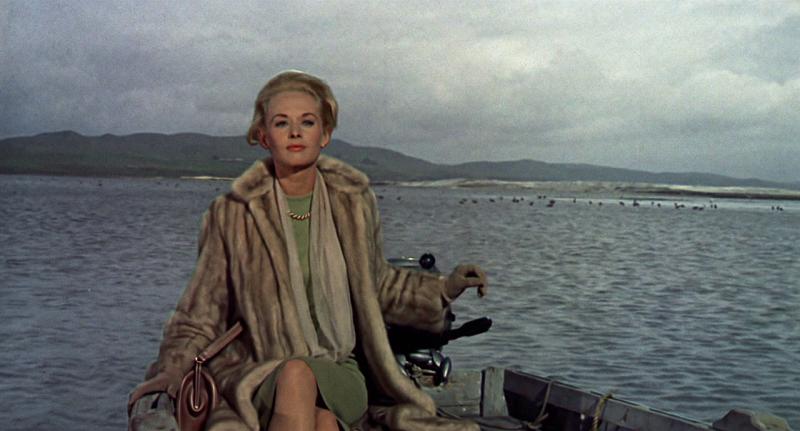

Many such absences of music accrue, fusing Melanie's smooth composure, impassive face and impeccable style. In fact she becomes more 'inhuman' as the film progresses. It is hard to watch the scene where she plants the bird cage in Mitch's bay house without admiring how a woman in a fur coat and stilettos can row a boat across a lake and perform such a cunning task without messing a hair on her head. While the scene's aural dynamics refuse to manoeuvre changes in dramatic degree of the actions depicted, the absence of music instils this protracted scene with a haunting quality that brings into sharp relief every action, movement and gesture. Far from being cued to respond to rises and drops of drama, we project dramatic build-up onto this empty soundtrack, willing her to get away with her trick and to get caught at the same time. Music cues conventionally moralize such incidents, hedging us to empathise with a character. Remove the music and you disperse an amoral climate, effectively 'amoralizing' the drama and displacing the viewer/auditor from controlled streams of empathy.

The birds themselves narratively thrive in non-musical silence. Rather than embodying or transmitting a superimposed musical logic which tags them as monstrous, malicious and maniacal, they speak in their own voice to their own kind. Their language is foreign, alien, avian, excluding us from the inner mechanisms of their motives and operations. In sync with a decultured slant on nature, these birds simply have no concept of the human. Accordingly, human musical codes do not stick. No JAWS-style orchestral throbbing salaciously trumpets their arrival. As in their attack of the children playing Blind Man's Bluff at a birthday party, the birds orchestrate and enact a cacophony upon their arrival. Balloons burst, children scream, feathers flutter and beaks peck, all played against a continual delivery of bird squawks. In the absence of music, all sound becomes terror; gulls and children scream alike.

A peculiar type of silencing occurs when Melanie waits for Cathy: a silencing through music. Most of the following incidents are covered by an irritating cannon voiced by the lacksadasical tones of children singing in school:

This scene is no mere set-piece based on undercutting 'mood'. Tension is painstakingly created by juxtaposing the deadly delicacy of the situation with the harsh ringing of childrens' voices. Devoid of non-diegetic orchestral tones to put us on edge, the innate and unpolished humaness of their voices serves to offer them as fodder for the abject inhumanity of the silent crows. It is even as if they are ignorantly conjuring up more birds with each refrain. This silencing 'through' music is yet another return of the terror of illusion: the innocence of the singing child - long exploited as a penultimate trigger of humaness in audio-visual history - is here a retainer of fate more than a container of pathos.

Formal orchestration of bird noise

The title THE BIRDS is simultaneously blunt and unspecific. It could be referring to any birds, some birds, all birds. It could indicate a group anywhere between 2 to 2 million. It could be aligned to species, family, genus. It eventually means every bird, and every bird potentially belongs to the dreadful mass of THE BIRDS. As forecast by the musique concrete overture during the title/credit sequence, bird noise is circulated and distributed throughout the film following this logic. The highly orchestrated soundtrack expands and contracts with the flux between dense sound of massed birds and sonically isolated elements of single bird movement.

When the sparrows first invade Mitch's house, their entrance is announced by the insignificant tweeting of a single sparrow who seems to have aimlessly flown down the chimney. Melanie - by now accustomed to reading the ominous signs of silence and emptied sound fields - prompts Mitch, her voice instantly swallowed up in a wall of bird noise. This 'wall of noise' is more of a three-dimensional space which terrorizes the empty domestic domain. As we move from shot to shot, not the slightest difference in acoustic perspective can be monitored. The mass screeching sounds the same in the centre of the room, on the floor, in any corner. The sheer density and volume of the multiplied frequencies becomes a total noise from which there is no escape; there is no alcove or pocket the noise does not occupy. Further, the sparrows occupy the totality of the audio-visual spectrum. Once again matted as an abstracted planar field movement over the actors flailing their arms and cowering in terror, the sound of the birds obliterates all other space in the soundtrack.

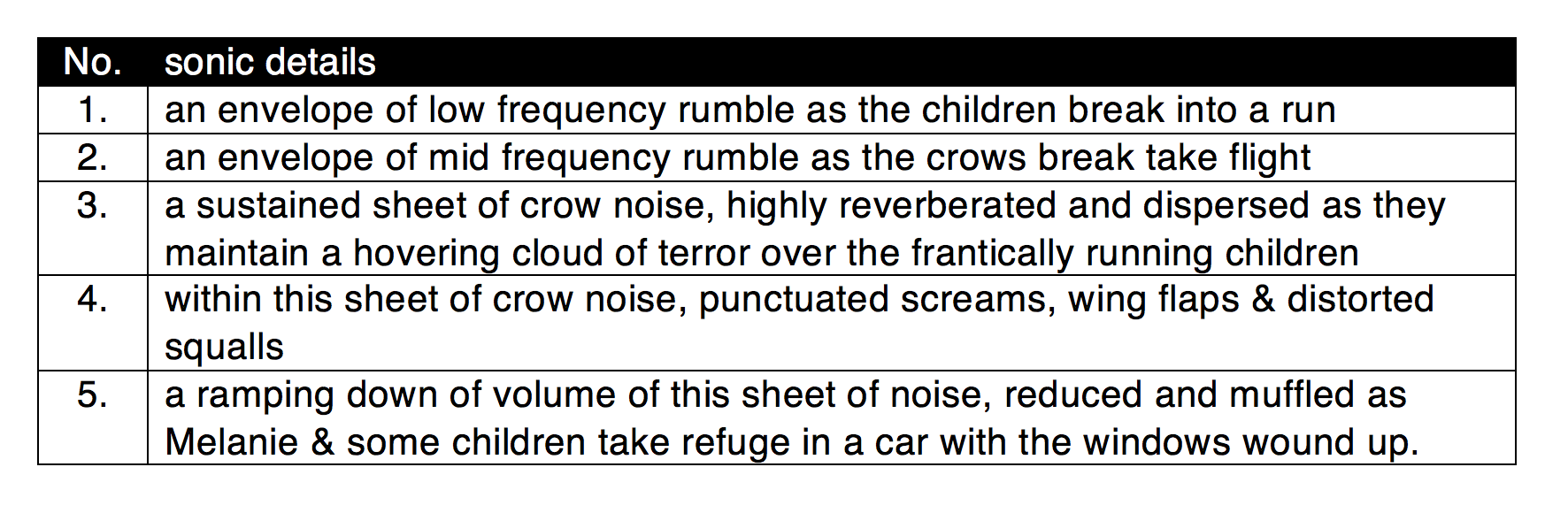

A similar yet distinct orchestration is played out following a prolonged build-up as the school children try to sneak away from crows. If one shuts one's eyes, one can distinctly hear aural layering reminiscent of the symphonic approach taken in many musique concrete compositions:

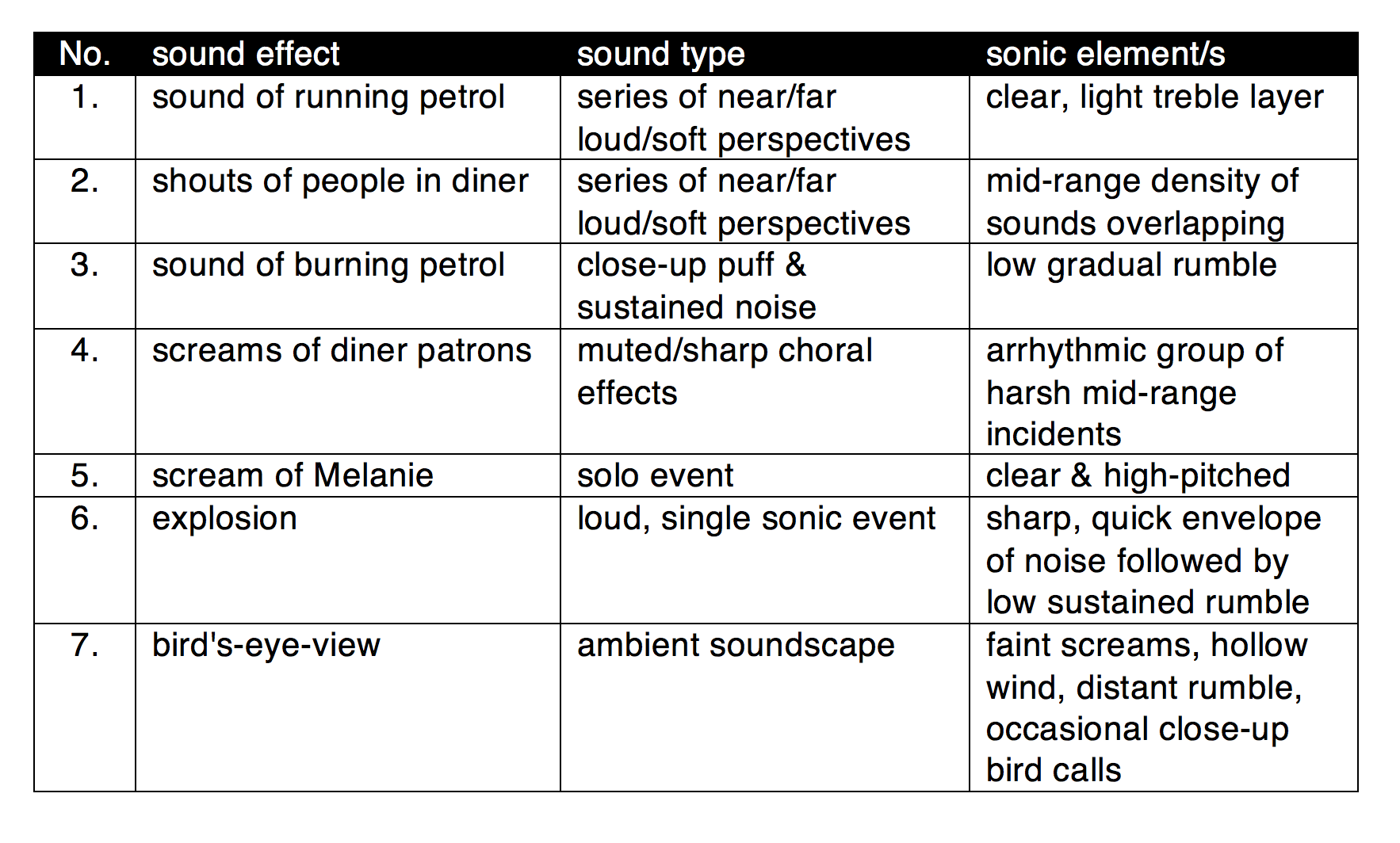

Just as the sparrows earlier are treated as a mass of sound, so too is the sheet of crow noise unbroken and undiluted. Rather than thinning out into individual crow sounds, the complete aural texture fades down in combined volume, suggesting that the existence of the birds is predicated on mass and not individual birds. A more complex and multi-layered sequence develops in the petrol station attack. It features a linear dramatic shape, starting low and building to a climax, then dying down. The aural dynamics of each of these components are crucial to the controlled deployment of the drama, enhancing and marking the rhythm of the drama, as well as temporizing it by making dramatic events match the dynamic shape of the aural events:

Prior to Melanie becoming involved as a witness to the petrol station explosion, a key scene condenses the film's approaches to aural orchestration. When she is trapped inside the telephone booth, moments, incidents, spaces and occurrences are swirled and concatenated, with emphasis on perspectival shifts in the sounds of bird noise, human screams, running feet, gushing water, a car crash, smashing glass, and so on. The telephone booth's confines serve as a sensory realignment chamber. Melanie sees all through the glass free from physical contact, while she hears less but with increased physical sensation. Chaos surrounds her on all sides while water, gulls and fists hit the glass and create sonic booms inside her terrorized space. This is one of many ironic retributions against the voyeuristic characters of the film, and the telephone booth's sensory realignment is a typical inversion of normal audio-visual relationships. While such states can be suffered subjectively within a character's mind (and distorted/stylized sounds would represent this), Melanie must endure the terror at the hands (or wings) of forces outside of her own mind. Put another way, it is as if she is trapped in the mind of someone being terrorized by imaginary birds, and as such is a symbolic conduit for the means the film uses to psychologically unsettle and terrorize us.

The dominance of bird noise over the human voice

By the film's midway point, the plot forces all characters to concede that there is something unusual about the behaviour of the birds. We too, as viewers/auditors, tread lightly as the film is brimful of harbingers of death. Most importantly, silence and sound become key markers of terror more so than the sight of a bird alone. This shifts our human perceptual sense of visual primacy into the auditory realm which for many animals is the primary field within which they assess danger. Sound without sight may be the ultimate terror for the human untrained in reading sonic signs, and THE BIRDS preys upon the viewer/auditor by incessantly mismatching the two and exploiting the ultimately arbitrary representational codes which fix the two together.

In the opening pet shop scene, Melanie, Mitch and the saleslady have no problem talking over the bird noise. Perhaps the fact that the birds are caged subliminally gives the characters a sense of aural control over the situation: they believe and feel that they can make themselves heard. By the end of THE BIRDS, many a character has been silenced - acoustically, figuratively, terminally. The collective chin-wagging which builds in the diner gives way to collective jaw-dropping in wake of the birds' devastating attack on the school and petrol station. The ornithologist talks too much: she is left half-framed in profile, stripped of the power of her words. The same events lead the concerned mother to hysterical accusations after she is powerless to silence the adults' inconsiderate chatter in ear-range of her children. Even the most humanized and domesticated birds - Cathy's lovebirds - just won't communicate with each other.

As Melanie witnesses the petrol station carnage, she is left speechless in a series of hysterical jump-cuts. She revives the voyeuristic effect of previous scenes, but this time her displacement from the action induces stress rather than pleasure. Her awareness of this accentuates her powerlessness: the jump-cuts represent the time that literally disappears as she realizes there is not enough time to warn the man holding a lighted match standing in a stream of petrol. A lag follows, after which she and the others scream out too late - screams which perversely attract his death due to him dropping the lighted match after straining to here their calls. Their cries are silenced by the gas pump detonation.

Silence reaches the zenith of terror in the Brenner household. After spending much time and energy fortifying all potential entrances into the domestic domain, the family lie in wait - obviously trapped like birds in a cage. An unnerving silence precedes the attack as everyone (us included) waits for something to happen. It does. The soft sound of a few birds merrily chirping cues the sonic assault which follows instantaneously. Sound now is at its most abstract and most deafening as electro-acoustic sheets of noise totally replace all lip-synch dialogue - visibly inaudible as Mitch gathers everyone into place. An equally inaudible hysteria ensues as no one knows where to go. This sense of alienation is intensified by numerous unmotivated camera angles which make the loungeroom space as alien to us as it is to the characters trying to take refuge there. As with the earlier sparrow attack, the soundtrack is devoured by bird noise - but here there is not a bird in sight. This is pure, unadulterated sound, recalling everything from Chinese water torture to Muzak to sonar crowd control guns to industrial noise deafness. An apocalyptic decimation of personal space: relentless, invisible, deafening. Ironically, the first lip-synch dialogue heard as the birds leave (signalled by a decrease in the roar) is "they've gone". This scene demonstrates the extent to which the birds are represented both as sound and by sound.

After the cacophonic climax of the Brenner attack, Melanie cautiously checks the attic. All is still and quiet - until she unwittingly shines a torch on the massed birds roosted there like a cancer within the household. They swoop on her as she flails her arms desperately like a man trying to fly. Her cries for help slowly disintegrate into a field of whimpers, gasps and fluttering wings; she lapses into catatonia, recalling her stilted silent scream as she witnessed the petrol station incident. The soundtrack impassively documents the near-silence that ensues as her near-lifeless body is pecked at by near-noiseless birds. The silence truly is deafening here, because the birds know that they have her: they need no longer communicate to each other untranslated directives for procuring her body. She is now carrion; they need no clarion. The birds - hitherto named vaguely - reveal themselves to be psycho-genetic amalgams of carrion crows, desert vultures, scavenger gulls. They terrorize us from above with sophistication and precision dreamed of in military aviation. They feed off our cadavers in disrespectful piecemeal fashion. And in a fitful triumph of the sonic, they peck out our eyes. As we die and fade to black, so does the film's sun set, blurring the calm chattering of all those gathered birds into an agitated chorus that reverberates deep in the caves of the hollow sockets which were once our eyes.

Cited soundtrack incidents in chronological order

1. Bird sounds and images occupy the audio-visual screen during the title sequence.

2. Melanie converses with a saleslady in a bird store while loud bird noise continues unabated. Melanie meets Mitch and further dialogue develops over the bird noise.

3. Melanie delivers caged love birds to Mitch's apartment, followed by a neighbour.

4. Melanie travels in her car with the love birds from San Francisco to Bodega Bay.

5. Melanie takes a hired boat from the port to the back entrance of Mitch's house. She enters the house and delivers the love birds, then sneaks back to the boat and watches through binoculars as Mitch discover the birds. She rows back to the port as he watches her through binoculars. He drives around the bay while she motors the boat to port. She is attacked by a gull as she and Mitch arrive at the dock together.

6. The children's birthday party is interrupted by a gull attack as Cathy plays Blind Man's Bluff. Balloons are burst and children are pecked.

7. A flock of sparrows suddenly invade the Brenner loungeroom and terrorize Melanie, Mitch, Cathy and Mrs. Brenner.

8. Cathy and fellow classmates sing in class as Melanie waits for Cathy outside. Melanie smokes as they continue singing. She notices a single crow the discovers a flock gathered in the playground. She enters the school to warn the teacher, who then dismisses the children to exit quietly.

9. The children break into a run and disturb the crows. The crows attack the children as they run screaming. Melanie gathers Cathy and another girl into a car for protection.

10. Birds attack the petrol station and diner exterior. A pecked gas attendant falls and leaves petrol spilling downhill. The gathered diner patrons see the petrol trailing to a man standing near a gas pump. He lights a cigarette; they scream a warning to him; he drops the match on the spilt petrol and blows up the gas pumps. Seen from high above, the birds survey the disaster.

11. A variety of birds attack the Brenner residence from the outside while everyone remains locked inside the loungeroom. Mitch fortifies the barricades and repels attacks by gulls.

12. Melanie checks the attic and accidentally disturbs massed birds with her torch. They attack her and peck her to near-death as she falls into catatonia.

13. Melanie and the Brenners exit the house and leave Bodega Bay by car as the birds roost everywhere.

Text © Philip Brophy. Images © Universal Pictures.