Rewritten Westerns - Rewired Westerns

Rewritten Westerns - Rewired Westerns

Lawyers in Cars & Monsters with guitars

published in Stuffing No.1, Melbourne, 1987One might well ask : where would classical cinematic narrative be without the Western? A multifarious yet solid history of writing has certainly fused the two in terms of iconography and morphology, trailing Porter to Griffith to Ford to Hawks to Boetticher to Peckinpah. From the epic to the poetic to the psychological to the political, the development of the Western has been as much invention as convention - inverting, reverting, diverting and subverting its own motifs and themes. In its multi-articulate sprawl, it is a history that illustrates Modernism as a historical development founded on the avant-garde(s)' incessant attack on its own conventions, with the past fuelling the future.

But times change - and so do histories. The more frequently asked question over the past ten years has been : where is the Western? It is not, as one might initially suspect, an idle, nostalgic wondering. [1] The 'decline' of the Western evidences the festering wounds of Modernism and its avant-gardes, plus the crisis of genre as a critical discourse. And if one follows the fused line of the Western with cinematic narrative, surely the latter must be in some dilemma due to the former's displacement. As the most decayed and overwrought of movie genres, the Western could well be a valuable corpse whose composture can illuminate attempts to address these problems.

In examining the history of the Western from this position, one must discern the genre and the genre's criticism as distinct areas which combine to produce the contemporary problematic of the Western. Genre criticism has invariably oscillated between myth and symbol by analyzing, respectively, a genre's thematic flows and its visual formalism. Each recourse has attempted to block the other's impasse with newness or interest generated either by a thematic organization of conventional icons (delineating the shifting polarities of individualism, racism, corporatism, imperialism, etc. in the genre) or a narrative distribution of a new or alien iconography (eg. cars, beaches and Chinese rupturing the genre's archetypography).

In its recourse to literary interpretation, the thematic approach all too often posits a film as being trite at the expense of discovering its more complex cinematic effects (and simply mentioning cinematography does not rectify such shortcomings). More specifically, it is perhaps an imperialist form of criticism in that its critical quest is often anthropological, attempting to comprehend American history and society through its own myth and folklore (hence the inevitable 'Vietnam' Westerns). Film & Society is no doubt a thorny, theoretical concept, but it is not as omnipotent as to force us to continually use the cinema as a social observatory. [2] Some Westerns are cinematically most interesting when one disregards the mundane inevitability of their social origins and reflections.

The iconographic approach echoes the cultural priority of the visual in the cinema, privileging visual codes above others. In critical relation to Modernism, one finds the Western's development as a desire to always look new - hence a history of tangible and discernible differences in material and plastic manipulation. The 'newness' must always be 'perceivable'. Of course, as the avant-garde of the 20th century has clearly demonstrated, there is a certain saturation point in newness, where one can no longer construct the unseen. This particular impasse colours genre histories as unimaginative serializations of form and content : reworked, rejuvenated, reconstructed, replaced.

Throughout the seventies genre criticism - embodying thematic and iconographic approaches - started to exhaust itself by devoting too much attention to the promotion of classical models via historicist views (searching for seminal examples) and essentialist concepts (searching for pure examples). Any notion of specific contemporaneity in more recent films was thus neglected, as 'contemporaneity' was viewed more under terms of cinematic realism (new icons produced by new research) and social myths (new issues to be addressed) than a substantial and self contained generic outgrowth from the classical models. [3]

The seventies, tellingly enough, was the decade of the coffee-table book : pictorial (ie. visual) histories of Hollywood genres, each ending with final chapters asking : where do we go from here? The real irony is that many of those books have since been reissued with an additional chapter which will detail an extra decade of film production and still ask that confounded question - without having qualified what happened in the ten years since they first asked that question!

Perhaps we should replace the shallow futurist aspirations of 'where do we go from here?' with a firmer grasp on the present : what are we doing here? The ultimate critical cop out (next to bemoaning that "genre is problematic") is to state that things haven't changed. Genre criticism may well appear to have exhausted itself (for deserved reasons detailed above) and the genres themselves become saturated - but genre films are being made today. Somewhere between the exhaustion and the saturation, we are still able to divine and divide genres ; we can still perceive genre. The production of genre films is thus not problematic - but we still have to reconcile rises and falls in production with rises and falls in their critical histories. In the case of the Western, it is not so much explaining why Westerns were in decline in the later seventies [4] as it is reconsidering all those films which were deemed impossible or awkward to relate to established critical modes and classical generic models. This article then devotes attention in detail to the Western in its general so-called decline - from around 1960 to the present and does so by looking forward through the Western, rather than back through its history.

* * * * *

While some genres saw rebirths courtesy of the great nostalgia binge of the seventies (with Musicals centering on the growing sociology of Camp, and Gangster movies working overtime on exploding Hollywood myths of its origins) the Western's motifs were already nostalgic, having mixed folklore and popular culture to produce a nationalist mythology for the start of a new century and a new society. Left out of a latter day first order nostalgia and belaboured by its excessive generic permutations, the Western of the seventies (which of course bleeds in from the sixties) took two major paths: the Hyper Realist and the Mutant.

The HYPER REALIST WESTERN is motivated by a combined desire to present the West in a historical light rather than a mythical or nostalgic one, and modernize the Western as a genre from a thematic base as determined by its material construction (dialogue, acting, cinematography, editing and soundtrack production). Its concern is in rewriting the Western, directly acknowledging the genre's history in relation to American history, and implicitly acknowledging the voiced concerns of genre criticism. (Some of the examples detailed : Will Penny, The Wild Bunch, Butch Cassidy & The Sundance Kid, The Culpepper Cattle Company, Little Big Man, Heaven's Gate.)

The MUTANT WESTERN is comparatively destructive in nature, utilizing the whole history of the Western (and caring little for the West) as a site for perversion : to deface its icons, obliterate its themes, and desecrate its very status as a genre. As such, it rewires the genre in the wackiest way possible for comic and/or political effect, exploiting its iconography in a way that sidesteps the saturation levels reached by formalist methods. (Some of the examples detailed : The Terror Of Tiny Town, Red Garters, Jesse James Meets Frankenstein's Daughter, Westworld, Zachariah, Rustlers' Rhapsody.)

Now, there is no classical model for either of these sub genres. Nor are there any stylistic codes, visual motifs or thematic strains which help to clearly form them. Rather, they are held in place by a series of tensions and intentions wherein the Western was/is seen as a site for reworking cultural, mythical, sociological and cinematic conventions. However, modulations of modernism and modernity are foresaken for the plain itch to use the Western in order to make a statement. Hyper Realist Westerns and, more so, Mutant Westerns are primarily gestural.

I must point out here that the main problems in qualifying these sub-genres (or rather, tendencies in generic construction) are typology in the case of the Hyper Realist Western (can hyper realism ever be a constant?) and genealogy in the case of the Mutant Western (is transgression not a fundamental process of the cinema as an art anyway?). But as a critical strategy, the placement of Hyper Realist Westerns broadens the historical notion of anti Westerns by evaluating them as actual productions of cinematic language more than socialized products of thematic concerns ; and the categorization of Mutant Westerns expands the short circuiting problematics of iconographic manipulation by voicing all those non Westerns neglected by conservative paradigms.

As open ended, non-unified and multi-dimensional as these sets of films are, they do collectively provide a way of navigating the blocks which genre criticism created for them (intentionally or unintentionally) in the seventies. So, to chart these rewritten and rewired Westerns, we'll have to rewrite and rewire history:

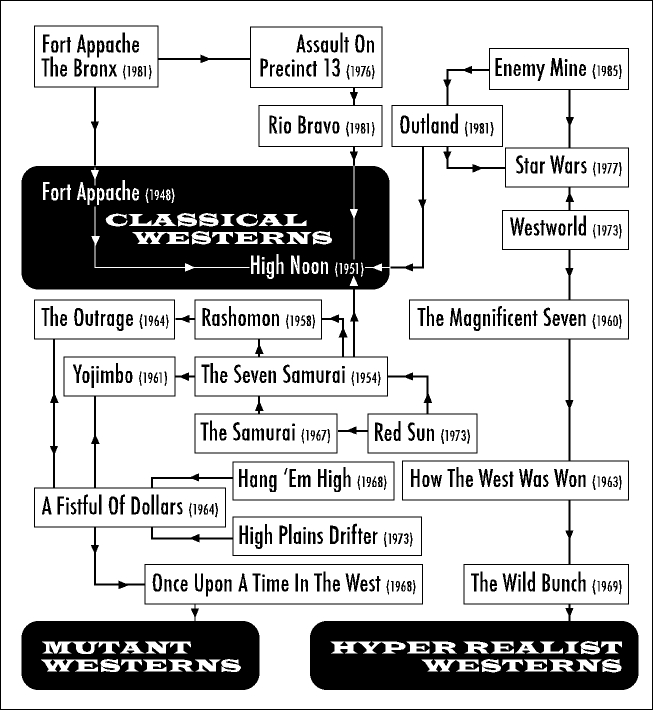

The above chart is not expository, and has only been constructed to lead us to the Hyper Realist and Mutant Westerns. Modelled on a rhizomatic approach to historical discourse (fracturing the linear and chronological with the lateral and simultaneous) this chart contains linkages which are assumed knowledge, though some attention should be drawn to a few finer details.

The films Fort Apache and High Noon have been highlighted purely to indicate an underlying density in the phase(s) alluded to variously as the Renaissance/Epic/Psychological/Serious Western. [5] Many classical generic models take this period (early forties to late fifties) as a thematic and even ideological preparation for the Westerns of the sixties. My chart should thus be understood as a strata from a cubic or molecular form, wherein critical and historical discourses based on the thematic and iconographic hold this particular strata in place. As you can see, for example, my flow into the Hyper Realist realm (signposted most obviously by The Wild Bunch) has no direct connection whatsoever with the post classicism of films like High Noon. As we shall see, Hyper Realist Westerns escape into the cinema via the critical acclamation of the The Wild Bunch, while Mutant Westerns constitute an aura that constructs the whole strata contained in the chart.

Hyper Realist Westerns

Everyone knew that the West was big in every way, and the mainstream introduction of widescreen patents allowed the Western to show just how big the West was. As 20th Century Fox's The Robe (1954) heralded Cinemascope as an advent of biblical proportion, Paramount introduced Vista Vision with Shane that same year. The mythical quality of Shane is largely due to George Stevens' cinematographic handling of icons and archetypes, marking him as a director who has consistently perceived the widescreen's capacity to dynamize its framed objects through the sensation of scale. [6] The credit sequence to William Wyler's The Big Country (1958) condenses Stevens' visual archetypes even further. Conceived by one of the maestros of credit sequences and film logos - Saul Bass - it is a virtually abstract fragmentation of horses' hooves, wagon wheels and saddle straps, collaged and superimposed over the coloured textures of plains and skies. Equally important is Jerome Moross' main title theme. Its tantalizing string cascades clearly echo Aaron Copland's definitive musicalization of Americana in suites like that of The Red Pony (1944). His rural epic style is also as much a bold precursor to Elmer Bernstein's score for The Magnificent Seven (1960) and its consequent appropriation by Malboro in their quest to represent the big West on the small screen. Copland's steadfast and imposing harmonic chords found their visual counterpart in the widescreen's vast and colossal Western landscapes. Moross and Bass distilled this combination for streamlined effect, stylizing Western iconography as high artifice and extreme plasticity - before the sixties had even commenced.

One can see this gigantic ideal of the fifties' widescreen Western welded onto the sixties' Western and its desire to rewrite and retell the West. How The West Was Won (1963) is as telling a title as The Big Country, and its bloated scope took three directors (Ford, Hathaway and Marshall) to tell its story. This $14m production introduced Super Panavision, a 70mm process developed from Cinerama (which had been competing with Cinemascope since 1953). However 20th Century Fox acquired a spartan sense of survival after spending $40m on Cleopatra, released the same year as West. Consequently, the likes of Super Panavision, VistaVision, Todd AO and Technirama were eventually superceded by Cinemascope's standard widescreen ratio of 1.85:1 as more theatres had adapted to Cinemascope than they did for Cinerama, thereby allowing Cleopatra to fail gracefully and West to flop abysmally. Fuelled high on aspirations to be definitive, West cued many Westerns to tell the story instead of a story; to rewrite the book of the West instead of adding a chapter. It is a prime example of the empty expansiveness and drained energy which set the scene for two important Westerns which start to polarize the Hyper Realist and the Mutant : Once Upon A Time In the West (1968) and The Wild Bunch (1969).

These two films open with strangely similar scenes : children playing with scorpions in The Wild Bunch, and Jack Elam being pestered by a fly in Once Upon A Time In The West. Apart from the moral and psychological relevance of these scenes to their ensuing plots, their widescreen effect of precision (Bunch) and claustrophobia (Time) demonstrate how their thematic tangents erupt from their iconographic restylization. This is a very important point : that their themes are effected, and not that such scenes simply portray their themes. [7]

Leone's flair for the spectacle is as much hinged on the suspense built up by contrapuntal editing as it is declared in the dimensional warps of the actual shoot outs, and the photography and editing of the Elam/fly sequence is just as operatic in its exposition. The soundtrack, of course, plays an important role: Morricone's score 'thematizes' its musical dynamics (as influenced by Bernard Herrman's notion of 'narrative music') and Rome's Cinecitta provides some incredibly exacting dubbing techniques, matching Jack Elam's sweat beads with the impression of fly feet on flesh. Cinematic effect is likewise demonstrated as Peckinpah's world of amorality and violence narratively pans out from the scorpion scene, fixing it as a trailer for the actual film and its wild bunch of philosophical disbeliefs in history and society.

Once Upon A Time In The West (Leone's 4th stamp on the spaghetti Western) is well known as part of his violent telling of the story of America (past, present and future) in bloody, bible like testaments. It is a mode of rewriting through extreme ellipsism, not unlike Straub's Not Reconciled (1965). But where Leone distills, Peckinpah boils, rewriting by graphically demythologizing America's past.

Storming into town amidst the dust already kicked up by Arthur Penn's Bonnie & Clyde and Robert Aldrich's The Dirty Dozen (both 1967), Sam Peckinpah's The Wild Bunch rewrote the Western in the prose of violence - the purest basis of action and dramatic conflict, and the driving spirit of America's progress. As pivotal pushes in cinematic language, Bonnie, Dozen and Bunch evidenced more a violence toward their respective genres than simply a contemporary, socialized depiction of violence. It became apparent that the predominant mode of generic development in the late sixties would be via issues of violence. (Indeed this has continued to today with Scarface (1983) and Rambo (1985).) But even though symbolic codes were continually being dissolved by graphic codes (replacing cinematic metaphor with photographic metonym) the materiality of cinematic language was evolving and changing in manifold and complex ways. Photography, sound and editing (to name the basics) were crucial in conveying the sense, feel and effect of violence upon which social identity hinged. Blood and guts and updated thematics are often pointed to as epicentral agents of the harsh modernity in these films, but their filmic construction constituted a language that affected film genre more profoundly than their timely contents.

A scattered historical patching leads up to The Wild Bunch. Arthur Penn's The Left Handed Gun (1958) closed the era of the so called serious Western (what a suspect concept!) with its neo-method acting and para-teenager sociology in the guise of Paul Newman's confused Billy The Kid. Based on a Gore Vidal TV play, it embodied an accent on character psychology notably associated with TV's Golden Age of Drama from the fifties. As much as that period played an important role in shaping film realism in the sixties, less recognized aspects of television had their effect on genre production. Consider how the generic explosiveness of the sixties Western relates to the TV Westerns of 1959: Earl Holliman played the Sundance Kid in Hotel de Paree as a reformed outlaw turned lawman and owner of a hotel; Don Durant played another gunfighter-turned-lawman in Johnny Ringo; and Michael Ansara played Sam Buckhart, an Indian appointed U.S. marshal in Tales Of The Plainsman. They certainly represent a sanitary trio desperate to liberalize the West without upsetting the status quo. The Hyper Realist Western can then be seen to have evolved in television as much as the cinema. Peckinpah predated Guns In The Afternoon (1962) with The Westerner - an apparently unusual TV Western starring Brian Keith, and which NBC produced for only thirteen weeks in 1960. Robert Altman cut some of his teeth directing sporadic episodes of The Rifleman and Bonanza, accounting for those series' occasionally off beat domestic situations. Coming from a different angle, Monte Hellman made two Westerns in the sixties which had a stilted telemovie feel about them - before telemovies were invented. Ride In The Whirlwind (1967) and The Shooting (1966) (filmed simultaneously - Hellman graduated from the Corman school of hard knocks) have many endearing technical imperfections (highlighted by wind drowning out dialogue) which encase sophisticated existentialist plots enacted by a post-beat/improv-lab cast featuring Jack Nicholson, Millie Perkins and Harry Dean Stanton.

Tom Gries proves to be a similarly important figure in the Hyper Realist Western. His Will Penny (1968) predates The Wild Bunch, and although it doesn't spectacularize its violence to the latter's degree, it contains two important streamlined elements: psychotic cowboys and liberated women. Donald Pleasence and Bruce Dern (the only man to have killed John Wayne in a film) play some bloody brethren whose savage attack on Charlton Heston types them as psychotics - a truly contemporary replacement for the bad gunslinger dressed in black. Leone's use of Eli Wallach and Klaus Kinski, and Peckinpah's use of Strother Martin and L.Q Jones are strongly related, as is Aldo Ray's version of a Nasty Canasta in Burt Kennedy's Welcome To Hard Times (1967). (As we shall find out in the Mutant Western, the psychotic cowboy attains sublimity in Westworld (1973).)

The liberated woman of Will Penny is Joan Hackett - complete with a kid and a murdered husband. Her voice is one of concerned humanism set against Heston's macho, solipsistic view of life. To a certain degree, this semi-feminist figure replaces the patriarchal fixture of the feminine/wife, and often affects the modern male protagonist with a broader view of his social surroundings. (Nonetheless, the so called liberated woman's feminist impulses are usually subordinated by the plot's priority in marking psychological change in the male protagonist.) It is important to note, too, that this liberated woman is not the macho woman who cropped up in a strongly connected set of films : Richard Brooks' The Professionals (1966) with Claudia Cardinale ; Andrew V. McLagen's Bandolero! (1968) with Raquel Welch; Tom Gries' 100 Rifles (1969) with Raquel Welch; and Burt Kennedy's Hannie Caulder (1971) and The Train Robbers (1973) both starring - you guessed it - Raquel Welch! In a blur of degenerate Mexicans, repressed millionaires, ransom demands and dynamited trains, the Cardinale/Welch macho woman was there basically to spit, scratch and scream, and go to town with bullet belts strapped across her bust, lighting dynamite sticks with her own cigar. (This type of macho woman is to be found more readily in the Women's Prison movies.)

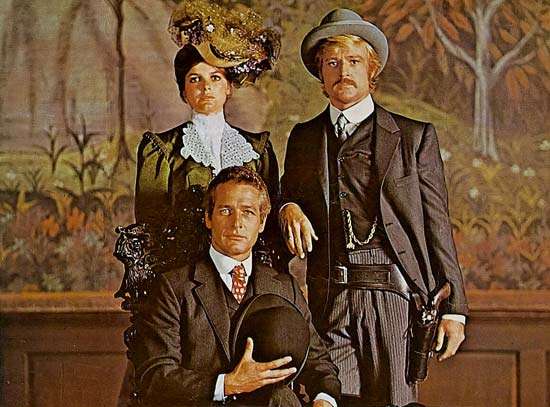

The liberated woman is central to the heroics (and anti-heroics) of Butch Cassidy & The Sundance Kid (1969), directed by George Roy Hill, another graduate from the Golden Age of TV Drama. Katherine Ross' liberated woman (the word 'liberated' seems more ironic each time I use it) is signified by her love for two men : a definite break in the classical Western's plot configurations which usually privilege men with such doubling. This modernized romance was exaggerated by Redford and Newman's status as studs for the 'new woman' who openly objectified male sex symbol. (Other notable Hyper Realist Western studs were Kris Kristofferson, Richard Harris, Warren Beatty, Gene Hackman and Steve McQueen : C&W Marlboro men whose relationships with the liberated woman signified their modern sensibility. Gets you right here, don't it?) Hollywood's general liberalization through the wild sixties thus allowed sex appeal to become a more overt narrative seme in the seventies, giving the Western a très moderne flavour.

In the case of Butch Cassidy & The Sundance Kid, it was a flavour made sugarly sweet by the film's angora photography and B.J.Thomas' drippy MOR ballad. By implication, Butch carries slight impressions of art film cinematography and youth culture sensibilities - two concurrences which seep in and out of many Hyper Realist Westerns. Consider: the ultra modern 'courtships' of Gene Hackman and Liv Ullman in Jan Troell's Zandy's Bride (1974) and James Caan and Catherine Bujold in Claude LeLouche's Another Man, Another Chance (1977) ; and the folk/rock styling of Peckinpah's Pat Garret & Billy The Kid (1973) and Walter Hill's The Long Riders (1980).

Butch Cassidy & The Sundance Kid attempts to remythologize the West (in contrast to The Wild Bunch's demythologization) into a part idyllic/part melancholic era, perfectly suited to its visual/aural softening. Its heroes are appropriately caught in a pseudo sepia snapshot as a thousand foreign rifles disintegrate the men into myth. Nonetheless it is an ending which pinpoints the Hyper Realist Western's polarization of its visuals from its soundtrack, painting a romanticized West as an epoch of simple values lost to the harsh controls of a mechanized, militaristic society. These polarities are thematically extrapolated in Peckinpah's The Ballad Of Cable Hogue (1970) and Robert Altman's McCabe & Mrs. Miller (1971) where progress is deliberately portrayed in a vein closer to home : machines, industry, business, corporations, etc. The railroad, the telegraph, cattle and fences were less relevant in the early seventies than the general theme of exploitation in these two films. However, short of Peckinpah's sharp, journalistic photography and Altman's multi layered soundtrack, these films carry only a general material tone of hyper realism.

An equally non plastic yet more specific thematic was to be found in Indians. A Man Called Horse (1969), Soldier Blue (1970), and Jeremiah Johnson (1971) collectively shame us (the white man) and inspire us. The simplistic and implicitly racist ideal of the noble savage was eradicated by a figure from whom we should seek respect, honoured in parables of ethnicity (Horse), exploitation (Blue) and ecology (Johnson). While the late sixties attempted to address notions of racial integration in Hombre (1967) and The Stalking Moon (1969), the early seventies portrayal of Indians took its cue from the then burgeoning industry of Blaxploitation. Thus they were presented as powers to be feared - all the more because they were probably in the right. Chato's Land (1971) portrays Charles Bronson as a supplanted black activist violently defending his rights, while Aldrich's Ulzana's Raid (1972) paints a gruesome picture of inevitable violence as Ulzana, the young apache warrior, clearly sees through the tokenism and double standards of the reservation. (This concept of the rebel Indian, though, is best represented in a Mutant Western Billy Jack (1972).) As a figure of the Hyper Realist Western, the Indian with cultural identity complements the woman with social motivation and the cowboy of psychotic disposition.

Even though these figures become stereotypes to be played with in the Mutant Western, they were primarily symbolic in the Hyper Realist Western, being images that conveyed themes more than they effected them. The Hyper Realist Western is perhaps best illustrated by a Western whose modernist thematics are so coalesced that the film's material surface provides a smooth finish, brightly detailing the precise cinematic nature of its hyper realism.

Such a Western is Dick Richard's The Culpepper Cattle Company (1971). [8] Once again, the credit sequence is revealing. Culpepper's parade of sepia toned photographs mixes actual photos from the era with restaged photos of the film's cast mimicking that stilted, pregnant pose, both needed for the medium's long exposure process and suited to the social formality of a new portraiture. (Consider the advertising trend of having films' characters pose for publicity stills as if they were having their photo taken in 1890, as in various posters for Butch Cassidy & The Sundance Kid; McCabe & Mrs. Miller ; Bad Company (1972) ; The Life & Times Of Judge Roy Bean (1972) ; and Pat Garret Billy The Kid (1973). Note also a similar 'old world' formality in many of those titles.)

In Culpepper's photo montage, the West and the Western are fused under terms of simultaneity almost as if it is a documentary about a film made during the West. At the turn of the century, the growth of photography paralleled the closing of the Western frontier, and both photography and the cinema played as much of an archeological and anthropological role as it did a mythic and nostalgic one. Likewise, the hyper realism of Culpepper works not so much by processes of re/demythologization as it does by transfusions of the epic, the lyric and the folkloric, presenting the West "as it was" through a poetic banality that romanticizes everyday life. In this light, the desire of Culpepper (a desire of the Hyper Realist Western in general) is to make the photographic come to life.

Pinpointing the photographic medium as a structural base for these films, one can perceive the precise role of their cinematography. Paralleling the theme of the virgin West, the cinematography carries a crafted feel of amateurism : scenes will be shot directly into the sun; the filmic grain will be textured by under exposure; focus will swim and waver through soft lensing and diffused lighting. The Hyper Realist Western predominantly leans toward a semi fine art sensibility, painting rich scene of golds and browns with a delicate palette. This is not to say that all these films are 'beautiful' to look at. Rather, they accent detail in order to enrich the everyday life of the West.

In a documentary fashion, Culpepper consciously details the initial scenes of the camped cattle train through a long tracking shot, capturing a set of theatrical vignettes : a cook preparing the food, a blacksmith shoeing the horses, a cowhand repairing the wagons, etc. The Hyper Realist Western will often detail similar scenes in order to show us the finer aspects of Western survival, taking in everything from drawing water from cacti to making coffee on an open fire to rolling tobacco for chewing. Close up photography here does not so much 'iconographicize' its objects as it resembles pages from National Geographic. Other notable examples of this attention to detail are Phillip Kaufman's The Great Northfield Minnesota Raid and John Huston's The Life & Times Of Judge Roy Bean (both 1972) with ludicrous extremes reached in Michael Cimino's Heaven's Gate (1980). (In contrast to this concentrated documentation, food preparations - for example - in the spaghetti Western are usually inserted for overwhelming effect, from Lee Van Cleef's minestrone in The Good The Bad & The Ugly to Terence Hill's baked beans in Trinity Is My Name (1971).)

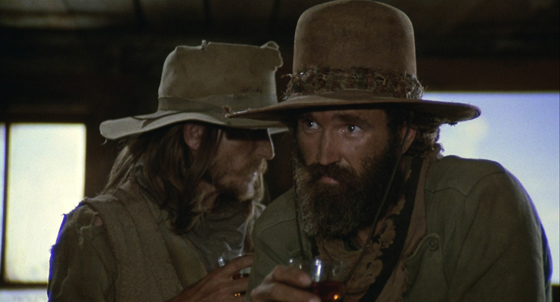

This documentary detail carries over to the visual appearance of Culpepper's characters. Their style connotes a certain anti-Hollywood finish : long, scraggly, unwashed hair ; craggy, blistered, unshaven faces ; plus enough dust, sweat, grime and mud to provide a second skin for the cowboy. Ironically, the Australian release title for Culpepper was Dust, Sweat & Gunpowder (edited to 50 minutes!) a title that fortuitously pointed to the purported physical substance of everyday life on the Western frontier. Such an ambience was well captured by the on location Western, and the Hyper Realist Western was likely to call for more dirt than hold it back.

This ambience also determines the colours of the Hyper Realist Western. Shane's striking juxtapositions of bright tan and vivid blue was replaced by a murky mix of browns and greys as the filth of the cowboy virtually camouflaging him against the barren landscapes of frontier towns. Consequently, colour is blended in the Hyper Realist Western, centering on tonal definition and textural separation well suited to its sensitive cinematography. Colour separation will only be called for when harsh dramatic conflicts occur. In Culpepper, the cowboys' introduction to the quaker settlement conveys a clash of philosophies through the visual contrast of their grime to the quakers' green grass and dark blue outfits. Likewise, the white tones of snowscapes are thematically propelled in McCabe & Mrs. Miller and Jeremiah Johnson. But more often, a blending of colours reflects the general dissolution of clearly defined moral sides in the Hyper Realist Western.

In its desire for a particular realism, Culpepper is careful to suppress or lessen those filmic elements of production strongly connected with a film's auteurist presence - namely, camera work and editing. As Leone stylized and restyled his orchestrations of time and space, Peckinpah developed a pragmatic ellipsism in his narrative method, slanting his camera work toward news reportage so as to intensify the majesty of his slo-mo explosions (which in themselves are allusions to similar scenes in Kurosawa's The Seven Samurai). Both Leone and Peckinpah are involved in spectacles, though from different angles. Culpepper features a saloon shoot out that serves well as a commentary on these modes of spectacle.

In opposition to Leone's cathartic resolutions and Peckinpah's vainglorious finales, Culpepper presents the shoot out as an anarchic detonation of confusion, desperation and chance. A split second after the shoot out, all the characters are still trying to figure out whether they have killed or been killed by the other guy. The editing is extremely important in replicating this state as part of our identification with the scene - we are just as confused. The quick editing is fractured to effect a graphic real time in contrast to Leone's condensed time and Peckinpah's expanded time. The general philosophical tone of the Hyper Realist Western covers nihilism, existentialism, pessimism and solipsism in its basic attitudes toward death, but precise and peculiar approaches to editing are crucial in distinguishing the subtlety of these films.

Last but not least is the soundtrack. It is primarily because of Morricone's polyglottic fusion of musical styles that the spaghetti Western is forced into the realm of the Mutant Western (consider the 'S&M ballad' during the POW interrogation scene of The Good, The Bad and The Ugly!), holding only archeological ties with the Hyper Realist Western in its early formation in the early sixties. Culpepper features a musical collaboration between Jerry Goldsmith and Tom Scott, with lyric/vocal interludes provided by Mamma Cass. Goldsmith's Western scores include Lonely Are The Brave (1962), Bandolero! (1968), 100 Rifles (1969) and The Ballad Of Cable Hogue (1970). Tom Scott's musical style is a laid back mix of soft jazz and rock ballad, from his session work for James Taylor, Carole King, Donovan and Harry Chapin, to his own outfit, The L.A. Express. The collaboration was understandably calculated, providing a score that reinforces the folkloric undercurrents of the film. Its orchestral arrangements (mainly using high strings and muted horns to signify the aura of the land's cairn. controlled power) are blended with melodies played by banjos, guitars, harmonicas and jews harps. This particular fusion evidences that continual wavering between the epic, the lyric and the folkloric. It constitutes a 'musical realism' (in keeping with the surface of hyper realism) through underplayed and unobtrusive scoring and evocative period-styled instrumentation. The effect is that of combining a modern tone with old style.

This notion of unobtrusiveness is to be found in the sound design of many Hyper Realist Westerns. As in Culpepper, continual ambience is favoured over dramatic organization. A myriad of aural details will often synchronize the documentary style visuals in their delicate denouement, creating a dense texture to unfold the West "as it was". As a technical mode it parallels (and in some cases simulates) Altman's technique of live multi-tracking, encompassing an aural environment as opposed to focusing on its key acoustic constituents. Such a technique is not unlike the depth of field cinematography to be found in Orson Welles' early work. The narrative difference, though, is whereas Welles Would overload his mise en scene (and this includes his soundtrack layering of effects and dialogue) for dramatic intensity, the Hyper Realist Western (in step with the cinema's general view of on location mise en scene in the seventies) overloads its sounds and visuals to signify a lack of dramatic organization - going for a 'mess-en -scene' to simulate the general messiness of 'real life'.

Culpepper is not a classical model for the Hyper Realist Western. However its codes and effects are dense enough to readily illustrate the genre's essential impulses. The Hyper Realist Western finds its boom period between 1969 and 1973, signposted by The Wild Bunch's forcible break from pre existent and consequent Mutant strains, and Pat Garret & Billy The Kid's incorporation of youth/counterculture sentiments and sensibilities.

The Hyper Realist Western's boom period ends here for many reasons. Western comedies were starling to provide the loudest voice for the genre's themes and icons. Norman Tokar's The Apple Dumpling Gang (1970); Burt Kennedy's Support Your Local Gunfighter (1971); the sequel to Support Your Local Sheriff (1964); Jerry Paris' Evil Roy Slade (72), made as a pilot for an unmade TV series; Ted Kotcheff's Billy Two Hats (1973); Robert Downey's Greaser's Palace (1973); and Mel Brooks' Blazing Saddles (1974) ranged from post Disney cuteness to anarchic and sometimes brutal parody, collectively forming a strategy that cared little for dealing with the West as either a cinematic issue or a site for articulating issues.

Television started to pulp major Hyper Realist concerns more in accordance with a desire to update and rewrite its own era of TV Westerns (throughout the fifties and sixties) than in acknowledgement of the cinemas forays into the genre. Hec Ramsey (1972-74) was set in 1901 and noticeably tried to be more of a historical/rural series than a Western, while Alias Smith & Jones (1971-73) continued in the light-hearted dramatic vein established by Butch Cassidy & The Sundance Kid. More importantly, TV Westerns became more contemporized - in terms of image - Kung Fu (1972-75) - and time - Cades County (1971-72) (which featured Mancini's pastiche of Morricone's spaghetti melodies). The latter two series cross-bred with the Hyper Realist 'rodeo/cowhand/parole' subgenre: films like Lonely Are The Brave (1962), Hud (1963), Baby The Rain Must Fall (1968), Junior Bonner (1972) and J.W.Coop (1972). (The year of the TV rodeo Western, incidentally, was 1962: Empire, Stoney Burke, Redigo and Wide Country ).

Finally, the voice of youth culture had already been screaming and continued to scream in the Mutant Western when Peckinpah enlisted Dylan and Kristofferson. Youth culture was thriving off all forms of perversity and sacrilege, so little potential was further realized in the cinema from Pat Garrett & Billy The Kid. [9] Conversely, the West (as described in the HyperRealist Western) affected youth culture more than is generally assumed.

A whole network of sub genres influenced by Western and Western themes and images forged dominant flows in American Rock from the Ole sixties to the mid seventies. From the acid West of San Francisco's Quick Silver Messenger Service and The Charlatans, to the East Coast folk of Bob Dylan (and his Canadian expatriates, The Band), to that bulging style from the San Andreas Fault Line known as West Coast Rock : Gram Parsons, 'The Flying Burrito Brothers, Poco, The Eagles, Emmy Lou Harris, Linda Ronstadt, Little Feat, Ry Cooder, Crazy Horse, Crosby Stills Nash & Young, etc.. Seventies Rock culture welcomed cinematic realism under the rubric of naturalism, and West Coast Rock typified the void of post Hippy calm and pre Yuppie fever, accumulating all the major tenets of 'getting back to the land' as well as the modernized glorification of the folk balladeer, canonized in the likes of Woody Guthrie. (Personally, I think it's the most lethargic, uninspired and boring period in the history of Rock!) It should also be noted that Dylan and Kristofferson weren't the only recording stars to grace the Western with youthful stubble. Don't forget Roy Orbinson, Fabian, Johnny Cash, Bobby Darin, Elvis Presley, Willie Nelson, Sony Bono, Ricky Nelson, Nancy Sinatra, Glenn Campbell, Duane Eddy and Frankie Avalon. (And lastly, an interesting curio here is the English group Bad Company - a familiar film title - whose Burning Sky album cover featured an accurate take-off of the poster for The Wild Bunch.)

As the Hyper Realist boom period ebbed into isolated bursts in the latter seventies/early eighties, the treatment of history as a discursive subject within the Western genre was centered on. Penn's Little Big Man (1972) highlights this by constructing its story as the flashback of 121 year old Jack Crabb, Custer's scout and sole Survivor of the Little Big Horn. Greatly publicized as a product of incredible research (like most major Hyper Realist Westerns of the seventies), Little Big Man is not as concerned with rewriting the West (a violent cinematic practice) as it is with calmly and 'truthfully' revealing the historical mechanisms that construct both the West and the Western. Of course it is just as sentimental, lyrical and mythological as the next Hyper Realist Western, but its narrative visualization of the oral history process indicates its use of the Western to question history. Robert Altman picked up the problematic of historicism in Buffalo Bill & The Indians (or Sitting Bull's History Lesson) (1976) deliberately using Newman to explode his own Hyper Realist stud stereotype in a cynical narrative that attempts a sincere yet severe debunking of culturally slanted history. (But as far as 'history in film' goes, these meaty problems have no doubt been tackled in more depth elsewhere over the past decade, from the asceticism of History Lessons to the seductiveness of Song Of The Shirt.)

As for Indians, their survival in the cinema was liberalized - and vaporized. Following the Sun Valley Conference of 1976 titled "Western Movies : Myths & Images" (co sponsored by Levis and held in Sun Valley on the eve of the American Bicentennial - that's what I call playing with history!) there has been a marked avoidance of historically representing the Indian. The conference featured (among other things) panel addresses by the likes of Iron Eyes Cody and Chief Dan George, who according to conference reports [10] left strong impressions on both participants and guests. The Indian has since been a representational spirit wandering through other genres. In particular, consider Will Sampson - the wise silent one in One Flew Over The Cuckoo's Nest (1975); the ethnic exorcist in The Manitou (1978); and the spirit medium in Poltergeist II (1985). He also narrated the documentary mini series Images Of Indians (1980) whose intention of rewriting is evidenced in its title.

It is worth noting here how John Wayne survived through the Hyper Realist Western. True Grit (1969) has its fair share of the Disneyland in its stubborn yet caring handling (via Wayne's persona) of women and youth issues - symbolized by Kim Darby's impulsive actions and crazy ideas. The image of Wayne with reins in mouth and blasting two rifles declared that the Western might be sagging, but Wayne sure ain't. His character from True Grit turned up in Rooster Cogburn (1975) teaming him with Katherine Hepburn in a Westernized scenario of African Queen. Wayne's image as The Westerner is sadly and ironically painted in Don Seigel's The Shootist (1976) as he is joined by James Stewart and Lauren Bacall in an elegiac tale of has-been gunfighters in an Easternized West. The Shootist is made all the more mythic (in this self reflexive mode so typical of Wayne's later Westerns) by Wayne's death, making it his last film. Such an event played at least some part in the cultural presumption of the Western as a dead genre at that point in time.

After The Shootist (though certainly not because of it) the Hyper Realist Western existed mainly in artistic exercises of academicism and auteurism. Penn's Missouri Breaks (1976) is a strange film because it condenses a whole cluster of Mutant strains and pressures them with Hyper Realist codes. The teaming of Brando and Nicholson forces the spaghetti Western and the counterculture Western into pitched battle, with perverse flair (Brando) eventually getting its throat slit by desperate realism (Nicholson). In a similar strategy of clashing sub generic histories and tendencies, William Wiard's Tom Horn (1981) stands as an ambiguous pick at the Marlboro Man, with Steve McQueen wandering across scenes that resemble moving billboards. As a bounty hunter, his days are as numbered as his escapees in the West's (and the Western's) closing frontiers. Ironically, it was also McQueen's second last film.

Heaven's Gate appears to have been just as jinxed as Tom Horn and The Shootist. Michael Cimino's Wagnerian Western illustrated the growing tendency to arrange all manner of critical discourse around the economic production of a film. Such critical procedures need to be seriously questioned. (Does it follow that, for example, Ride In The Whirlwind is as much a visualization of its shoe string budget as Heaven's Gate is of its $40m?) Gate's financial disaster coincided with the incredible hipness 'the industry' was starting to attain. As films were being advertised and adjectivized by their budgets, every critic and his dog started using the word 'industry' like previous critics had used the word 'art'. Gate was a satanic god-send for criticism in general : a financial flop, a flailing genre and a failed auteur. But in terms of Hyper Realism, it amounts to a desperate will not to reveal history (Little Big Man), desensitize history (The Wild Bunch), or update history (McCabe & Mrs. Miller), but to be history - all encompassing, all embracing. Gate's West attempted to not be a world, but to be the world, typing it as a Mega Hyper Realist Western. With dinosaurian ideals, it died accordingly.

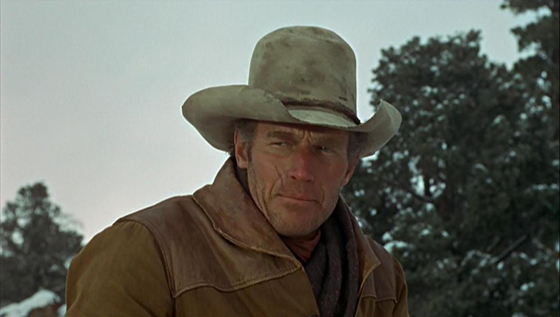

Post Heaven's Gate, some quiet academicism/auteurism has continued. Fred Schepisi's Barbarossa (1982) rode the wave of Third World novelty along East Coast streams of middle class taste, balanced as a quirky homage to the modernist power of the genre. Lawrence Kasdan's Silverado (1985) is notable mainly because of its date and its inclusion of John Cleese, otherwise one suspects it will only live on as an undistinguished example of post Hyper realism. And finally, Clint Eastwood's Pale Rider (1985) repeats Leone's act of teetering between the Mutant and the Hyper Real. Self consciously oscillating from, respectively, High Plains Drifter (1973) to Joe Kidd (1972) and Outlaw Josey Wales (76), Pale Rider looks back on Shane almost as if to wonder 'how does one make a Western today?'. However as a transplanted spaghetti Western set in frosty locales, its grasp of the modernist Western's now greatly multiplied figures and symbols is too loose to sculpt a stance for the film. Even though some inventive casting (Michael Moriarty and Christopher Penn) determines the film's more original aspects, its title serves as an allusion to the Hyper Realist Western's increasingly transparent aura - Pale Rider ...

Mutant Westerns

If the Hyper realist Western is determined by concern, control and command, the Mutant Western is determined by the absence of those factors. The mystical ethic and mysterious aesthetic of the 'artistic decision' (which has pumped up the historical notion of auteurism into a regrettable universalism) plays little part in the Mutant Western, because the realms of its production cover exploitation, subcultures and multi/trans-culturalism. The romantic ideal of the artist addressing society with his message is totally confounded by these realms, because in the Mutant Western there is either (i) no artist; (ii) no message; or (iii) no society to address.

In most Mutant Westerns there is something wonderfully in their lack of care or respect for professional production standards. As films, resemble mistakes, accidents, disasters, flukes, oddities, facades, charades - but they are all cultural mutations : hybrid in form, polymorphous in texture, multiple in direction, of course, their richness is founded on the rigidity of 'normal' Westerns - or rather, the critical assumptions and prescriptions of classicism, professionalism, auteurism and art which culturally underline dominant histories of the Western and critically undermine many other possible histories. This proposition of a Mutant Western, then, is born of critical and historical analysis.

Let's start with the B Western serializations from the thirties. (This is not an essential place to start, though, for just as classical Western history can be traced back to nickle and dime pulps and pre photographic epic paintings, Mutant strains probably extend right back to contemporaneous exploitations of the West itself.[11]) Producer Jed Buell and director Sam Newfield made a film in 1937 that indicated the way West for Mutants. Advertised as "the world's first outdoor action adventure with an all negro cast", Harlem On The Prairie (1937) either predates the Blaxploitation phenomenon of the seventies or shows that black audiences have always found a complex and perverse delight in their absurd stereotyping in white productions. Harlem's popularity was enough to generate what appears to have been a full but short lived trend that included other pictures like Harlem Rides The Range and The Bronze Buckeroo (both 1939). It must be remembered, though, that these films were then somewhat naturalized' by their context that of the B Western, which was more concerned with an arbitrary yet particularized form of action (horses, guns, whips, cattle, fisticuffs, etc.); a succession of stars ranging from the stoic to the singing (from Hart and Hickock to Rogers and Autry); and a generic permutation based more on novelty than invention (incorporating spies, submarines, ghosts, slave traders, short wave, radar, detectives, Wall Street, aeroplanes, radio stations, singing competitions - you get the picture). 'Blacks' were simply seen as another permutation whose crossover potential could increase the films' market.

But perhaps more startling - and more isolated - was another film by Buell & Newfield: The Terror Of Tiny Town (1938). Readily described as an all-singing all-midget Western, it still has to be seen to be believed. The cowboys (and cowgirls) are all under four feet; ride Shetland ponies; nip under swinging bar doors; fall back when they shoot their standard sized guns; drink from ludicrously large beer mugs; and use twenty seconds of screen time every time they climb on to their high stools to sit at the bar. But the exploitative quintessence of Terror is that it implodes, almost destroying all intended effect in its execution. The film continually shows the midget cowboys desperately trying to control their Shetlands, and at least one third of the film's dialogue is totally lost by the sub standard recording of the midgets' constricted and distorted vocal delivery. This notion of imploded exploitation figures strongly in the Mutant Western in that some of them are further mutated by the inadequacies and contingencies of their production.

For a variety of reasons (most of them suppositional) Mutant Westerns are not easily found throughout the forties [12] : the B Western continued in an increasingly standardized form, effectively cancelling out its Mutant potential; the Western 'proper' refined its psychological and thematic contents; and an overall leaning toward social realism in America's post war condition possibly had its effect on the narrowing of anti social/off beat options. Whatever the causes were, Mutant strains were in a definitive slump in the forties. Only an honourable mention could possibly be awarded - to Lash La Rue's twenty odd B Westerns from the late forties, where he used his bullwhip in a way that Eastwood would shoot his gun in the eventual spaghetti Western. (In 1985, Lash La Rue was signed to star in two low budget Horror films : The Dark Power and Alien Outlaw. If they ever get made they will be definitely be Mutant Westerns! In the meantime, another 'Horror Western' has been set for release in 1987: Ghost Riders.)

Throughout the forties and into the fifties, Musicals intensified their production, involved in a love/hate dialectic with radio, records and Broadway. Many stage musicals were set in the West (and the Western.) but their solidification as musicals allowed for little mutative growth. Invariably corny in tone, one stands out at least face toward the Mutant Western : Red Garters (1954). Directed by George Marshall and starring Rosemary Clooney, Jack Carson and Gene Barry, it spoofs the Western as a genre more overtly and directly than other Western Musicals like Annie Get Your Gun (1950), Calamity Jane (1953) and Oklahoma (1955). It attains its strangeness by actually retaining its theatrical form. The sets are incredibly stylized, setting the action in voids of pure colour with a surrealistic suspension of facades and constructions that schematically represent the Western town's locations. (This type or set design is relatively conventional in stage craft, but is rarely transferred to film set construction.) Red Garters can be viewed as a precursor to Demy's use of sets and colour in his widescreen musicals of the sixties, and it even obliquely relates to the over stylization of the Western town (in reality a literal and actual facade of civilization planted in the wilderness) in Zachariah (1971).

In a similar effect of retainment (causing ontological confusion by combining differing craft modes) the TV series Sgt. Preston Of The Yukon (1955) is a most extreme non adaptation of a radio serial. This early colour TV series is even more stilted than the B Western serials from the forties featuring Sgt. Preston and his trusty dog, Yukon King. The Sgt. Preston TV series boasts a narrative as skeletal as Red Garters' sets, and Richard Simmons acting is more wooden than the prop pines in the studio. A different kind of TV stiltedness is in the early B&W series of The Life & Legend Of Wyatt Earp (1955-61). Hugh O'Brien plays Earp with more Brylcreem than Bill Haley, and the series resembles a bunch of elder teenager rebels playing cowboys. The continual sub gospel vocal only warbling provides a music score that makes the show even weirder.

Stemming from the thinness and publicity of such television productions, two early Roger Corman movies are minor landmarks in the Mutant Western: Apache Woman (1955) and The Gunslinger (1956). Collectively, they play Johnny Guitar (1954) at high speed, making up for what they lose in psychological subtlety and complexity with outlandish and hysterical plots and character interactions which posit their macho woman of Joan Taylor and Beverly Garland miles ahead of their nearest runner up, Raquel Welch. This Mutant Western duo breaks enough codes of historical, mythical and sexual representation to place them 'up there' with Johnny Guitar were it not for the technicality of their originality. At the least, no account of Freudian impulses in the Western is complete without these films. (One should also note how strongly these Westerns resemble Monte Hellman's Ride In The Whirlwind and The Shooting in terms of the valuable complexity obtained from their production limitations.)

The Mutant Western really freaks out in the sixties. Curse Of The Undead (1959) followed the highly exploitative trend of blending cheap horror with anything. In this film, Michael Pate plays a vampire gunslinger, exaggerating Jack Palance's gunslinger for hire from Shane (1955) in an attempt to expand the Horror market (not the genre) further than the then recent Teen Horror fusion. The incredible rise of bland, correct-line TV Westerns during the fifties gave good cause for a Horror/Western amalgamation, but it was probably too late in 1959. In the sixties, such a fusion was deadened by its function as generic novelty, serving the new teen market with fare not unlike the staple for the previous generation's B serial audiences.

A related but more peculiar phenomenon was the Mexican Horror Wrestling film, headed by Santos - the man in the silver mask - and his decade of intense production from the late fifties onward. Like the B Western, generic novelty served as plastic wrapping for the integral wrestling bouts between the good guys (led by Santos) and some real mean tag teams who never tagged. Santos' stab at the Western is a definitive Mutant I would give my right arm see. Titled The Lepers & The Sex (196?) it features a gang of leper diseased gunslingers complete with neckerchiefs who engage in some deadly bouts with Santos. God only knows how 'The Sex' comes into it!

Two titles in the Horror end of the Mutant Western remain unforgettable : Jesse James Meets Frankenstein's Daughter (1965) and Billy The Kid Vs. Dracula (1966). Both directed by William Beaudine (a veteran of cheapness with no solid flair) they are perhaps the cleanest example of generic experimentation. In the most straightforward manner, they mix 50% Horror with 50% Western as beautifully illustrated in their titles. Horror elements rupture their Western surfaces (rather than the other way around, as in Django The Bastard) as John Carradine's Dracula really does look a few hundred years old, while Cal Bolder as 'the monster' (actually Jesse James' friend whose brain is replaced by Frankenstein's grand daughter) looks like a beef cake straight out of Muscle Beach Party. This type of rupture occurs later, albeit more politicized, in New Wave Westerns. Worth noting, also, is the way in which the two Beaudine Westerns unproblematically view history as a plan of global connections, linking mid 19th century Europe with the new America : what if Dracula did move to the States? Within their exploitative context, it is cast as a laughable proposition, but similar questions of concurrent histories crops up later in the Hyper Realist Western (The Wild Bunch, The Ballad Of Cable Hogue, The Shootist, Another Man Another Chance and Heaven's Gate).

As the spaghetti Western can now be seen to largely prefigure many Hyper Realist concerns, it must not be forgotten that their primary impulses reverberate within the Mutant Western. An often overlooked precursor to the spaghetti Western's thick blend of the Mutant and the Hyper Realist is Marlon Brando's One Eyed Jacks (1961). Brando is often regarded as both bastard and bastardizer of film and stage craft (bless him!) but he is also one of the cinema's key purveyors of perversity, consistently having used the cinema to demonstrate its value as a site for cultural and social gesture. In One Eyed Jacks, Brando transforms his capacity for rupturing method acting (he is actually the ultimate contra method actor, because he always deliberately theatricalizes his realist method) into violently self conscious direction.

Cut from its original 4'42" to 2'21", it concentrates key elements and figures for the sixties in the form of Hyper Realist concepts presented in a decidedly Mutant manner : the use of the Mexican coastline is highly inventive and undercuts the more conventional symbolism of the film's art direction; a continual complex of amoral double-crosses between key characters determines the spread of the plot ; the narcissism of Brando's character Rio is savagely portrayed in the sado-masochist beating he receives from Karl Malden as the sheriff, forcing him to learn to shoot with his left hand ; and Rio's appearance - a mix of Union blue and stylish sombrero - highlights his character as Other, responsible for a variety of social, mythical and racial transgressions. All these elements and themes are central in Leone's Dollar Westerns. Once again, the simple, historicist track back to the classicism of the American Western and the Japanese Samurai film is very misleading, as close analysis of One Eyed Jacks proves it to be, if you will, a tomato concentrate for the spaghetti Western.

It is broadly assumed that the spaghetti Western (in a painfully traditionalist sense) is all the more regrettable because of the endless imitations it spawned. [13] But it would be, more precise to say that the success of Leone's Westerns proved the malleability of the Western form and the expandability of the Western genre, thus opening the doors for Spain, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Sweden, Germany, France, Japan, Mexico, Italy and even Transylvania to each in their own way deflect and reflect the imperialist spread of the genre. To posit Leone's Westerns merely as exercises in style and theme [14] only reveals how limited superficial genre criticism is, because when Henry Fonda's blue eyes pierce the widescreen as he impassively guns down a kid in Once Upon A Time In The West, Leone is exploiting American film to make a statement based on complex dichotomies of appropriation/simulation and suture/rupture. (It is an effect that, for example, relates to Godard's appropriation of Jane Fonda in Tout Va Bien and Corman's exploitation of Peter Fonda in The Trip as recognized identities.) The fact that such broader cinematic and narrative issues were only more fully realized with Leone's Once Upon A Time In America (1985) further indicates that the thematic/iconographic trajectories of genre criticism fail to see both how genre is threaded within and throughout the cinema, and how generic manipulation (especially in the Mutant Western) generates discourses on the cinema.

Italian Exploitation films form a consolidated body for dealing with these often neglected areas of cinematic commentary. They also provide valuable and equally neglected insights on the more complex genealogical flows which make global film history so dense. [15] (The Leone/Fonda example is the tip of the iceberg - consider Argento and Fulci's use of Keith Emerson scores for Inferno and Murder Rock; Castellari's use of Fred Williamson in The New Barbarians; and Deodato's use of Michael Berryman in Cut & Run.) The spaghetti Western (which has to be continually evaluated, noted and perceived at the cross roads of the Hyper Realist and Mutant Westerns) requires recognition as a multi/transcultural phenomenon, ping ponging as it does not only throughout the Italian industry and the European market, but also across the Atlantic. [16]

We start, then, with Curse Of The Undead (1959) where the gunslinger as the walking dead mythically transfers the revenge thematic onto a plateau of surrealistic possibilities which germinate and eventuate within a number of trans-Atlantic crossings over the ensuing twenty years. In A Fistful Of Dollars (1964) Eastwood confounds his enemies with the illusion of a walking dead gunslinger, engineered by his concealed armour. Capitalizing on the novel success of that character, similar ethereal, monolithic gunslingers grew in other spaghetti Westerns. The most infamous was Django, star of a body of mega-gothic Westerns that treated Leone's symbolism as ordinary and went on to construct their own fantastic scenarios. In Django The Bastard (1969), Django is actually one of the walking dead; due to the film's excessive visual style it can be typed more as a Westernized gothic Horror than anything else. Similar generic stretching occurs in Tony Richardson's antipodean-Rock-Western Ned Kelly (1970), a crystalline tangent in this stream of hyper-mythical gunslingers. Consider the film's subcultural underlining : rock star in impenetrable suit taking on society and winning out as a legend - released the same year that Janis, Jim and Jimi died.

The Richardson/Jagger gunslinger constricts itself in comparison to Alexandro Jodorosky's El Topo (1970). Through a painfully obsessive yet limp Neo-Dada obliteration of conventional symbols, El Topo the master shooter walks across Western landscapes as a godly/ungodly spirit intent on penetrating the cinema through the Western's veneer. Supposedly created out of society's collective nightmares in the late sixties, El Topo today resembles a messy daydream, brimful of overworked imagery that no longer even carries its original value as a Mutant Western. Still, El Topo constitutes a definite link in this particular rhizome of the Mutant Western. While Ted Post's Hang 'Em High (1968) re-Westernized Leone's artistic traits and Eastwood's taciturn style, Eastwood's creation of his Euro-Americano persona for his own High Plains Drifter (73) as the red angel of death owes as much to Django The Bastard as it does to El Topo.

There exists a lateral connection on this plain of the gunslinger between the Hyper Realist psychotic cowboy and his Mutant counterpart : the 'perversely theatrical' psychotic cowboy. The former is a figment from a sociological nightmare, the latter a figure from an artistic fantasy. Examples of this Mutant psycho would be Brando in Missouri Breaks, and Robert Mitchum in Henry Hathaway's Five Card Stud (1968) where he caricatures his psycho preacher role from Charles Laughton's Night Of The Hunter (1955).

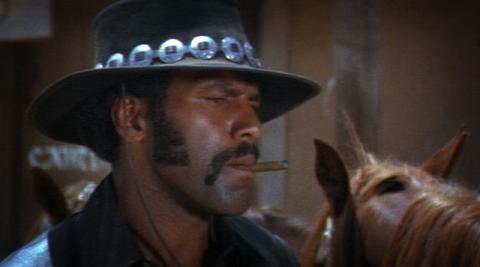

Believe it or not, Westworld (1973) is an incredibly important film here. Made the same year as High Plains Drifter, it totally shifted the axis of the mythical gunslinger, transforming him into a totally unstoppable maniac machine whose sole purpose is to kill. Westworld's title declares its scenario as pure fabrication, and ironically it is only a sense of realism that pushes the film into the sci-fi genre (robots, leisure, the future, etc.). Otherwise, Westworld uses the Western to fix a specific and identifiable type of terror by openly refracting Yul Brynner in his black shirt role in The Magnificent Seven (1960). Westworld's internal story is of two middle-class jerks who, literally, get trapped in a Western. Almost as if in repayment for this weird transgression, the Brynner-monster-gunslinger hunts them down in an appropriately para-human way. (This textual effect of Brynner within Westworld relates to Jodorosky in El Topo as another meta-narrative angel of death, though in comparison Jodorosky's over-coded symbolism appears too didactic to be truly effective.) With a bit of subtextual reorganization, the Brynner-monster-gunslinger (as a monster-within-a-genre) is a clear precursor to Jason (Friday The 13th I-VI) and Freddie (Nightmare On Elm Street 1-111) - both as a figure not required to define itself in terms of characterization, and as a vehicle for smashing genre in order to inflict effects with its splintered pieces. (This view of generic manipulation from within is in total opposition to the later Sci-Fi Western hybrids produced by the superimposition of icons on themes and vice versa : Valley Of Gwangi (1969); Star Wars (1977); Outland (1981); and Enemy Mine (1985) - even though Westworld is a possible progenitor to such productions.)

As much as I propose that Westworld realizes the latent potential of El Topo, many of the afore-mentioned Mutant Westerns are richer than the artistic/political Westerns of the New Wave era. Paul Morrisey's Lonesome Cowboys (1968) illustrates his main concern of accentuating a lack of dramatic craft through a preference for 'screen presence'. In Lonesome Cowboys, his performers' loose manoeuvres and gestures rupture the Western surface accordingly, although it could resemble a home movie made by 1890 cowboys if Super 8 had been around then. However, the West(ern) is simply another generic given in Morrisey's primary strategy of polarizing the screen surface with screen presences (not unlike Joan Crawford rupturing her own films with her presence). Godard's Wind From The East (1969) attempts a similar overlaying to highlight a political dialectic, but coming shortly after Once Upon A Time In The West and its ambitious yet considerably more potent political parabolism, East even lacks the absurdity that makes Lonesome Cowboys interesting. Godard's use of Gina Maria Volonte (Indigo from For A Few Dollars More (1966)) was no doubt intended to celebrate and analyze the spaghetti Western as much as Ford's cavalry pictures, but ultimately the lack of resolution is too deliberated, failing to generate any cinematic - let alone generic - tension.

While Hyper Realist Westerns had been developing and continued to develop political parabolism into the seventies, Mutant Westerns in this shadowy New Wave area followed the direction of Lonesome Cowboys. Perhaps their collective call sign was "Hey gang! Let's make a Western!". George Englund's Zachariah (1971), Dennis Hopper's The Last Movie (1971) and Marco Ferreri's Don't Touch The White Woman (1975) (and even Ulli Lommel's Cocaine Cowboys (1979)) all head West to play out the making of a Western.

The Last Movie supposedly puts on film the true story of its production : an intention to complete a modern Western in Peru. The cast shows the Godardian touch of mixing personae and personalities - Hopper, Fonda, Kristofferson, Julie Adams, Sylvia Miles, John Phillip Law, Rod Cameron and Sam Fuller. (Story has it that Hopper was 'studying' El Topo while editing The Last Movie.) As much as Easy Rider was a countercultural gesture to say that the Western was evaporating into the developing Road Movie, The Last Movie virtually self-destructs, as if to say that the Western could no longer be made. From what few accounts are available, [17] Marco Ferreri's rarely seen Don't Touch The White Woman lies somewhere between the political satire of Greaser's Palace (1973) [18]; the historical reworking of Little Big Man (1971); and Straub's black hole of absurdism Othon (1972). Mastroianni plays Custer and well-known Italian comic Ugo Tognazzi plays his Indian scout in a comic yet savage tale of imperialism. The film was apparently totally opportunistic in its production, hurriedly setting itself up in the freshly excavated site of the old market district in Paris, allowing Ferrari to set his Western incongruously in the obviously urban crater to ironically represent the West as a hole in the seventies, just as Straub set his Greek tragedy in Rome's Forum ruins to compete with deafening traffic.

Zachariah sits just at the edge of these New Wave-inspired Westerns, because whereas their productions violently declare cinematic strategies of appropriation, co-option, collusion, situationism and deconstruction, Zachariah's counterculture sensibilities (as pathetic as they appear today) are carried by a strong handling of aural and visual iconographic effects. Yet again, the credit sequence serves as a circulatory, self reflexive brace for the film. Complete with iris effects from shooting into the sun, and loose, flowing flute melodies over a melancholic folk tune (closely simulating "God Bless America"), Zachariah sets itself up as a Hyper Realist Western, not unlike The Culpepper Cattle Company made that same year. This arty opening then cuts from the sun's glare to the glint of a perspex guitar just as the flute is distorted by echo as guitar feedback fades up, and POW! there's a three piece Rock band in the middle of the desert, thrashing out some electric folk in the wild Rock vein of Hendrix's "Star Bangled Banner".

Scripted by The Firesign Theatre and heavily featuring Country Joe McDonald & The Fish, Zachariah is essentially a modern sociological slant on the morality tale, fusing the young rebel metaphor with a countercultural defloration of America's most sacred genre. Advertised as "an electric Western", it is a precise, surrealistic fusion of Rock with the Western, because were it not for the New York Art Ensemble and The James Gang popping up in saloons and brothels, its overall tone and visual surface would mark it more Hyper Realist (like Pat Garret & Billy The Kid) than Mutant (like Roy Orbison in The Fastest Guitar Alive (1967)).

The Mutant Western rocked in other ways, too. Boss Nigger (1975) is a very hip title for a Westernized tale of black power in an integrated society. Fred Williamson plays the self elected sheriff in an amoral, bigoted frontier town and runs into some predictable problems. Otherwise, blaxploitation was mostly leveled at reworking crime and gangster themes. Pornography is too large an area to account for here, suffice to list some deliberately hilarious Western inspired titles : Blazing Zippers, A Fistful Of 44s, The Sexy Dozen, and the least satirical and most interesting of the bunch - Raw : A Dirty Western, which is a cross between The Wild Bunch and Lonesome Cowboys with lots of raunchy Western women to spice things up. (Even Herschell Gordon Lewis made a soft porn Western: Linda & Abilene, 1969).

As the seventies moves into the eighties, perverse comedy provides main fuel for the Mutant Western. Robert Aldrich's The Frisco Kid (1979) casts Gone Wilder as a rabbi in the wild West who teams up with young robber Harrison Ford in a trek across America to - where else would a rabbi wander - the goldfields. Similar in satire to Aldrich's The Choirboys (1977) and California Dolls (1981), it is nonetheless hard to forget Wilder from Blazing Saddles - although I have been told that watching this film in a Jewish cinema makes you wonder what in hell everyone else is laughing at. Comin' At Ya! (1981) was the umpteenth attempt to revive the new and superior polaroid 3-D processes of the eighties, and why not try it out with the spaghetti Western? Directed by Ferdinando Baldi, it spoofs the Spaghetti sub-genre, only to prove yet again that the spaghetti Western was already too self-conscious in form and style to parody. That same year also saw The Legend Of The Lone Ranger (1981) : an equally failed attempt to carry over the comic boom of the late seventies into the Western by bringing back (as fake nostalgia) the adventure md romance of the serial in tongue-in-cheek style.

Much better in this attempted vein were the two 'return' films based on The Wild Wild West TV series (1965-70): The Wild West Revisited (1979) and More Wild West (1980), both starring the series' original leads. Recalling the post-camp of the series, the two telemovies are a heady mix of the Western, Sherlock Holmes and The Outer Limits. The Avengers TV series (scripted by Brian Clemens) had a similar 'wildness' in its dry pastiches, running concurrent with The Wild Wild West and other neo-Bond spy mutants like The Man From UNCLE. In an attempt to stretch these neo-Bond possibilities, Clemens directed the first of what was intended to be a series : Captain Kronos - Vampire Hunter (1974). It takes the gothic Western of the Django series into 18th Century Europe complete with Kronos ('beautiful' Horst Janson) as an Eastwood of few words. The sword fight in the tavern with Kronos against three psycho-heavies is a direct take on Eastwood's initial dazzling display of drawing skill in A Fistful Of Dollars. Both Kronos and The Avengers (not to mention films like Mario Bava's Danger: Diabolik (1968)) hint at what is no doubt a strong British connection in the sixties with Leone's conglomerative Westerns.

1985 - the year of Silverado and Pale Rider - saw two anarchic Western comedies: Paul Bartel's Lust In The Dust and Hugh Wilson's Rustlers' Rhapsody. Pre-production reports indicated that Lust would be another Waters/Divine/Hunter-style collaboration, but Bartel's incredibly uneven camp direction makes it a very aggravating film, proving that Divine is fairly limited without Waters' 'bad taste' acumen. It is definitely a Mutant Western, but the well known image of Divine is not as much a visual shock in the Western as Bartel had perhaps hoped. Rustlers' Rhapsody was advertised as another Blazing Saddles, and although it is probably not as riotous, its comic mode is a world away from Brooks. Written and directed by Wilson, it places (via a totally inexplicable burst both backward and forward, in time) the fictitious singing cowboy Rex O'Hearlihan (veteran of 38 movies between 1938 and 1947, so his voice-over tells us) in a modern scenario of the Hyper Realist Western. In an openly Brechtian manner, all the other characters in the plot can't believe the way Rex carries on with moral standards/early nights/no women/etc. and think he is very weird. The film is a well constructed network of internal fiction and meta narrative ruptures in its Twilight Zone framing of a post Brooks comic style. [19] Unfortunately its advertising killed it (how could a trailer explain the film's premise?) but it is certainly a Mutant Western worth looking at, especially as it has a better rhythmic sense in its oscillation between textual gags and narrative ruptures than either Blazing Saddles, Greaser's Palace or John Landis' limp The Three Amigos (1986).

Finally - though not surprisingly - the Mutant Western is alive and well in Rock'N'Roll. Just as West Coast Rock went hand in hand with the Hyper Realist Western boom period, a wide range of Rock acts have in the eighties tackled Western imagery in true Mutant style. New Wave (in the musical sense) irony in the late seventies can be related to the savage cover versions of Western oriented songs (Blondie's "Burning Ring Of Fire" ; The Dead Kennedy's "Rawhide" ; plus Devo's cowboy like image of the "spud boy", culminating in their brief appearance in Neil Young's Rust Never Sleeps dressed up like nerd cowboys). These examples are in a sense modern day versions of Zachariah, poking fun at America's most respected genre. A genuine departure from this aspect of social satire was Adam & The Ants, who lassoed the globe with their unbelievable bricollage of Gary Glitter's bloated Glam and Morricone's hyper stylistic Western scores. Labelled by Adam as "Ant Music", it was a short-lived but supreme musical equivalent of what the Mutant Western is all about.

After Adam & The Ants' worldwide success (and the inevitable backlash against what was a unique and isolated gem amongst many other tired Pop appropriations) it became many people's concern that there was something deeper in the West, something behind its overworked imagery that could be put to service by Rock music. (It also gave America new fuel with which to battle the endless waves of British Invasions.) The West, the Western, and - in particular - Texan mythology thus all became hip in a broad anti-Pop context. Some groups jumped the band wagon with tongues bulging in their cheeks while others were simply interested in combining a Western/roots flavour in their music. Both directions constitute a certain conventionalism (satire and roots) - but the general ironic distance (or tentative suspicion) at which they entertain this Western-ness qualifies their work as Mutant in comparison to the Hyper Realism of groups like The Eagles (who wouldn't know the meaning of the word 'distance' until they split up, cut their hair, and made 'dance music'.) Some of these groups in no particular order : The Johnnies, The Long Ryders, Lone Justice, Jason & The Scorchers, Wall Of Voodoo, The, Bum Steers, The Raunch Hands, Tex & The Horseheads, Blood On The Saddle, Jon Wayne, The Gun Club, The Le Roi Brothers, Rank'N'File, Charlie Pickett & The Eggs. [20]

Video clips like The Johnnies "There's Gonna Be A Showdown" and Boys Don't Cry's "I Wanna Be A Cowboy" condense the essential humour to be got from the Western, and through their streamlining indicate not only a disregard for any further Hyper Realist Western possibilities, but also the saturation point reached by the Mutant Western. But what sounds like an end could indeed be a start for something new: something that totally discounts iconographic parody, thematic obliteration and political metaphor to build a structure on the genre's sealed mosaic surface - just as The Culpepper Cattle Company was able to idealize its Modernist figures and gestures, and Westworld was able to transfer and transform the genre's impulse into a textual and cinematic device.

* * * * *

To say that the Western has withered and wilted is simply to give up formulating and synching new critical modes with films as they are being produced. Just because you can't critically articulate a film does not mean that film is somehow 'dead'. The notion of the Western as a living tree is inaccurate, because it would be better to say that its branches have been pruned, bound, grafted, whittled. The overall shape, form and structure of the tree (the Western) has changed, continuing to survive irregardless of whatever ideal form is proposed as a model for its 'healthy existence'. Such models should be as mistrusted as doctors' advice.