Particulate Cinema

Particulate Cinema

Visualizing Data & Posthuman Physics

published in Artlink, Vol.37 No.1, Adelaide, 2017Concept

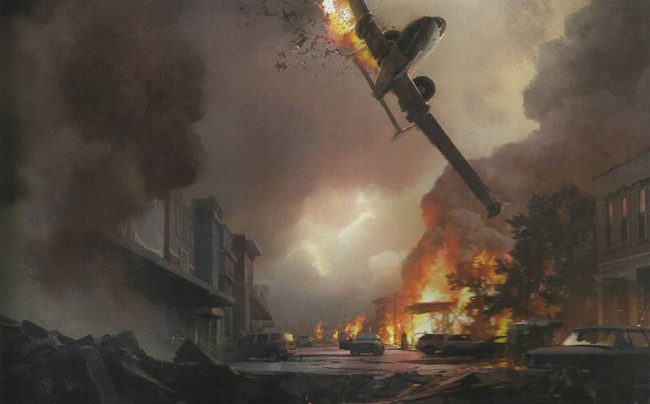

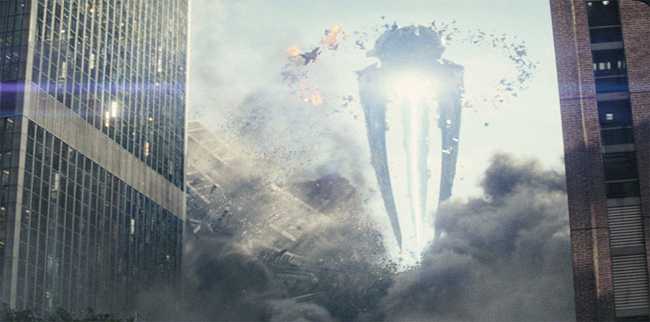

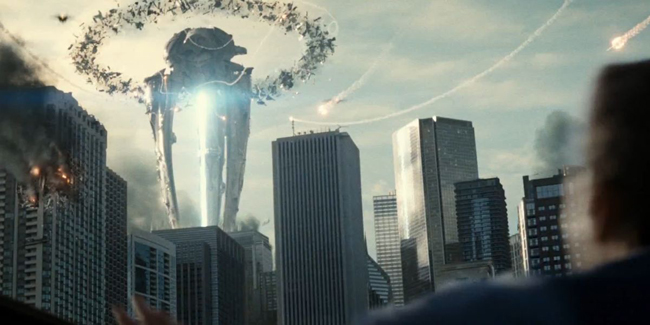

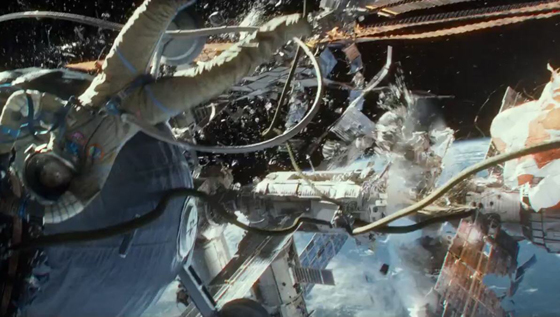

Particulate Cinema is a long-form survey of how data visualization has been deployed in big budget Hollywood CGI films. A range of overpowering hi-end films from the last 5 or 6 years in order are analyzed to demonstrate how data visualization strategies are easily co-opted, recoded and immolated. On the one hand, their use in these films sends a depressing message about how artists of all stripes are so easily fooled by data visualization’s promise, but on the other hand it evidences how Hollywood – as a dream factory of the most classical kind – inevitably reveals the flaws, sink-holes, blind spots and contradictions of their fantastic construction. Thus (for example), Mad Max Fury Road employs extensive use of dust-storm particle simulation to evidence the unresolved relationship between indigenous land and colonised mining; Man Of Steel constructs whole simulated cities in order to destroy them in a series of unspoken reboots of 9-11 PTS while never analyzing the bigger picture of why the US was targeted in the first place; The Day After fabricates glorified bad weather reports in order to reinforce Zionist dreams of separatist survival; Green Lantern is a cum-fest of liquefied fire, toned glowing green to invoke a reading of nuclear energy, bodily infection, and post-human probability.

These examples may sound opaque, but the idea is to show how data visualization software has shifted from Renaissance illusionism to Industrial tabulation in order to symbolise and fantasise how mystical and/or immaterial energies govern the contemporary world. Most of these films are abhorrent, but read as cultural signage, they arguably demonstrate how ‘visualization’ still needs to be written, read and interpreted. Dismissing these populist films can lead to missing out on some vital climatic responses to how artists depicts ‘life as we know it’ by using data visualization. Particulate Cinema is an introductory overview of the differing approaches to particle diffusion motion graphics, which has now become the primary means by which these meta and global approaches to ‘imagineering’ are being handled in everything from gushing rivers of Coke-a-Cola, smoke trajectories of WWII bomber planes, and swarms of butterflies around the head of a cute blonde child at a picnic in a civic park.

Semantically confused, symbolically chaotic, semiologically self-circuiting: this is contemporary cinema sine qua non. To read Hollywood’s current trend in hyper/supra/digi-movies as inferior, illegitimate, insubstantial or immoral is missing the chance to free-form how their acts and actions of visualization can fortify one’s ability to read their signage. Artists who accept the Assange/Snowden/Weiwei mandate to strive for a world shaped by transparency ultimately surrender skill in perceiving how visual languages obscure their purpose and effect behind multiple layers of encoding. Might it not be equally important to practice and strengthen one’s ability to deeply comprehend the shifting states and modalities of visualization? One wonders what art could arise from penetrating such opacity.

Some of the notions on imaging and digitization in Particulate Cinema are tagged in earlier published articles like Listening Noise & Other Musical Messages - World War Z and Voiding Effects & Terrorized Language - The Unreality of the ISIS Videos. Following the publication of my article Panoptic Spreadsheets & Political Art - Exit in Real Time, I was contacted by Artlink to write something on data visualization in relation to art. I counter-offered the start of the Particulate Cinema project. The Artlink article contains around 7 sections of the complete survey's 17 sections. The final survey will considerably expand upon the Artlink article.

Excerpt

(from the Artlink article)1. Making Movies

Movies used to be made. They were things: overwhelmingly sensational yet entirely immaterial in their manifestation of audiovisual eventfulness. In a sense, cinema produced things in a parallel universe running in tandem with modern art’s desperate drive to ‘immaterialise’ its artworks and ‘de-objectify’ its creative economy. Yet movies did this uncontrollably and inevitably. Are not movies large-scale, immersive, collaborative, multi-tasked, industrial commissions? And is that not what eventually became the imprimatur of internationalist biennales bent on spectacular production?

But movies have stopped being made for at least a decade. Now, they are visualised. The shift can of course be rationalised by the industrial embrace of digital production and the convergence of various screen technologies, formats and markets. The change from ‘making’ to ‘visualising’ is ontologically sensible. If movies were never things or objects, why were they said to be ‘made’? The answer lies in the conservative notion that artists create while technicians make (an embarrassing admission to Judaeo-Christian precepts of godly creation versus mortal manufacture). And just as the 20th century championed artists who created through distilled alchemical power and conceptual provenance, cinema fought for artistic legitimacy through auteurs, visionaries, genii and, well, ‘artists’. It’s a messy state of appellation, and one that still signposts 21st century art dialecticism of both populist and political bents.

Considered at a deeper level, much can be discerned in the evidential formations and subtextual mechanics incurred by visualising movies rather than making them. Unlike authored texts, heroic sculptures, expressive paintings and directed installations, movies are semantically confused, symbolically chaotic, and semiologically self-circuiting. Lacking as they are in singular voices and encapsulating didactic panels, they require a responsive reading of their textuality to audit their schizophrenic babble. And while that was always a difficult task with 20th century movie-objects, the problem is exponentially confounding with 21st century movie-visualizations.

2. Visualizing the Unknowable

So, it’s 2011. You’re a computer software designer. Here's your ‘creative’ brief. An evil being imprisoned on a desolate planet in another galaxy overpowers three alien soldiers who have crashed onto his asteroid. Thriving off pure fear in others, he sucks their life-force as fuel to grow stronger. How will you visualize this? Now hold this fleeting design dilemma — because that quandary of visualization governs how movies are now visualised. Thinking of ‘images’, you might rely on DaVincian anatomical diagrams, Symbolist paintings, Surrealist panoramas, Outsider Art pencils, late 19th C. corporeal realism, hi-tech body scanning. All things that pre-exist in the depository of data in the known world. You would end up with a movie that apes art, as if images are things that can be remade. But movies now use current technological tools not merely to represent, but to address how they will visualise something and why they will do it that way. Movies tasked with these acts of visualization generate a part-dumb/part-revelatory reflection on the current state of visualization.

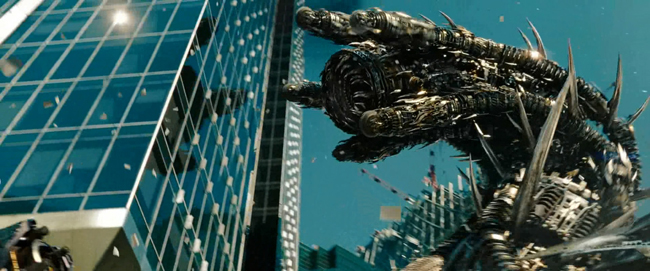

The above hypothetical scene is in Martin Campbell’s The Green Lantern (2011). Like all the ones to be mentioned here, it is an expensive, oppressive, artless, bombastic, numbing, offensive spectacle. But no judgement is being made despite those hot descriptors: this is precisely the type of film that indicates the shift from ‘making’ to ‘visualising’. Back to the scene. The disembodied walled-in head of Parallax opens his jaws and spews yellow molten ejaculate at the bodies of the soldiers. They hold their ground, though each has a shimmering yellow ectoplasmic skeleton slowly extruded from their corpus, leaving their physical body to crumple and their ‘fear energy’ to be gulped down by Parallax. The trick to the scene lies not in these characters and their drama, but in the material effects conjured through the use of advanced computer simulative processes based on particle effects, fuzzy logic behaviour, fractal diffusion, morphed texture-mapping, pixel-tracking and multi-planed visual rendering. The scene’s software sovereignty is devoid of plasticity and theatrics; no bodies, faces, costumes, sets or staging link its production to conventional moviemaking mechanics. Nor is this another bemoaned case of pure simulation, digital supremacy or virtual habitation of ciphers within a narrative. Despite its blatant unreality, this is more like observing through a microscope the sub-atomic activity which constitutes any occurrence of material existence, be it animate or inanimate. Let’s call it ‘particulate cinema’.

Many viewers would contend that the scene — like the bulk of imagineered CGI in big budget movies attached to Marvel and DC property franchises — apes pre-existing visual effects, like the zapping lightning arcs from Steven Spielberg’s Raiders Of The Lost Ark (1981) to Ivan Reitman’s Ghost Busters (1984). Yes, it resembles those scenes plus the following decades-worth of copies. But those older effects are flimsy optical overlays on real spaces, objects and bodies. They’re as ungainly as accents, wigs and girdles. Conversely, the opening scene from The Green Lantern functions as an unmarked key to comprehending how movies are now more about the materialization of energy forces than they are about characters, people, you or me.

The overwhelming micro-managed hyper-intensified CGI in movies like The Green Lantern signals something that visual art has long strived for: a dissolution of the viewer in the act of viewing. Art achieves this metaphysically; cinema engineers it somewhat cynically. It’s not surprising that the scene occurs on another galaxy’s planet, and that its beings have no correlation to our humanity. While the scene mimes its drama — declaring what’s happening to who and how — it subliminally intones that it is currently impossible to have the slightest idea of how things would transpire on another planet, let alone another galaxy. The randomised complexity of the multitudinous burning veins of melting bones and their wavering heat hazes and blurred artefacts confer the impossible scene with two discursive factors. Firstly, this is how heat, wind, suction, mass, gravity and velocity can be verified to perform in our known world. Secondly, this is how they could operate under hypothetical conditions unknowable in our world. It’s a fastidious examination of how things exist and what happens to them in unknowable conditions. Crucially, these elementals simultaneously support and contradict each other. This is how movies are now visualised.

(End of the Artlink article excerpt. Images for the rest of the article and the project are listed below.)

3. Representing Terror

4. Reverse-Engineering the Past

5. Preparing the Posthuman

6. Bending Steel

7. Creating Dust

8. Going Off-World

9. Disorienting Equilibrium

10. Limiting Cinema

11.Replicating Elements

12. Catastrophizing Nature

13. Televising Revolutions

14. Post-modernizing Mechanics

15. Becoming Data

16. Appropriating Politics

17. Making Art

Text © Philip Brophy. Images © respective copyright holders.