The Many Delphine Seyrigs in the Room of Chantal Akerman

The Many Delphine Seyrigs in the Room of Chantal Akerman

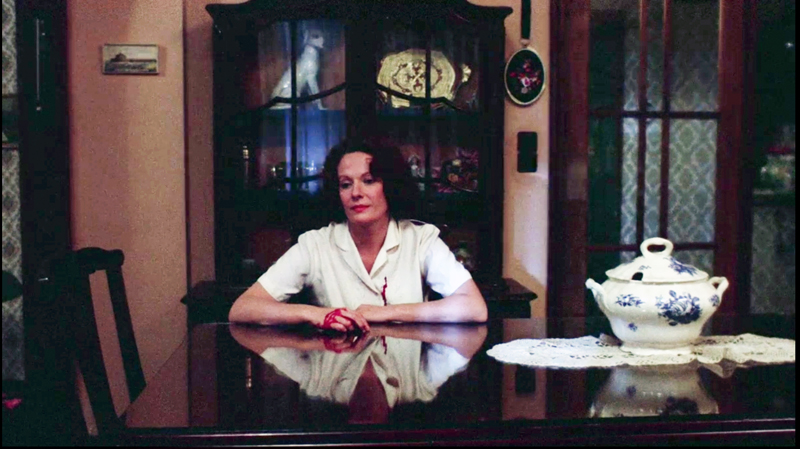

Woman Sitting After Killing (2001) in “Travelling”, Jeu de Palme, Paris, 2025

published in Senses Of Cinema No.114, 2025, MelbourneThe Chantal Akerman exhibition at Jeu de Palme, “Travelling”, celebrates a filmmaker renowned for her use of isolationist rooms—the psychogeographic qualities of chambers, cells, dens, bedsits, domiciles. [1] Equally acknowledged is Akerman’s exploration of transitory zones—particularly states of migration, dislocation, relocation, and other diasporic conditions of ‘inbetweeness’. “Travelling” focuses on these traits of Akerman’s preoccupations, and grants special attention to how Akerman paralleled her cinema with reversioned and reconstructed components of her films for museum installations. The exhibition presents Akerman’s status as a truly ‘intermedial’ artist, who took up the challenge not simply to make an art installation, but to compose installations from the materiality of her own films. While the exhibition as a whole was also devoted to expanding and exposing the various processes Akerman deployed in her practice (evidencing the open-ended means by which she developed her scripts and moved through pre- and post-production for her numerous features, shorts and episodes), it gave considerable space to a selection of the contemporary art installations she has produced.

I’d like to focus in detail on one: Woman Sitting After Killing (2001) 2. A 7-channel video assembled from a single looping moment from Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975), it was initially presented in “Documenta XI”, Kassel, in 2002. It is the first work one encounters at Jeu de Palme, installed to the left of the entrance in a slightly darkened, horizontal space. A gentle curve of seven CRT monitors on individual plinths shows a looping 5’38” fragment of the final scene from Jeanne Dielman. Widow Jeanne (Delphine Seyrig) sits at the dining room table, after having stabbed to death a male client whom she had earlier serviced there in her home where she conducts sex work in addition to her daily domestic activities. One’s encounter with the installation is initially visual: the eye is drawn to the minute shifts of movement in the locked-off frame of Jeanne fixed in position yet slightly altering her shoulders, neck, eyes and head. Devoid of tight multi-screen synchronization, the monitors are left to freely cycle through in-phase and out-of-phase timing, which accentuates the abrupt join of the loop-end to the loop-start. It’s like sheets of patterned wallpaper revealing visual ruptures by misaligned placement. Taken en masse, the curve of monitors perform like a temporal wallpaper, creating a uniform visual pattern which is repeated yet mismatched.

But something else envelopes the space: the film soundtrack. The clearest sound is the slight creak of a wooden chair as Jeanne subtly shifts her body weight. Also heard: slight envelopes of breath, as Jeanne sights, ponders, thinks, waits. Plus, the distant ambience of outside traffic, rising and falling in arcs of low noise. The visuals capture the type of numbing existential nothingness of domesticity and ‘invisible work’ (shared by homebound wives and bedroom-tied prostitutes alike, here composited into the multi-functional seme of Jeanne in the movie). But in this nothingness one can sense the pregnancy of the environment through the aural sensation created by the visualised space. For where there is space and time, there is sound: the materiality of presence that psychoacoustically enlivens and defines space as something inhabitable and experiential. Space is ‘immersive’ because it sounds itself: its ‘liveness’ (a characteristic of sound in a pre-recorded state) is registered not by the directional, focusable data-intake of ocularity (via your eyes) but by the duophonic registering of the multi-polarity of 360º acoustic sensations (via your ears). You are removed through sight: your eyes are a window onto the outside world. You are located within sound: it conjoins you with the outside world.

The sound of Woman Sitting After Killing become denser and more detailed as the speakers of all seven monitors replay the filmed scene’s audio with phase-shifted echoic timing. And here is where Woman Sitting After Killing becomes a sublime post-cinematic experience. For the preceding three hours plus in Jeanne Dielman, the titular character had become nothing. She sculpted, performed, presented, attired, represented and signified herself—to her clients, to the film’s audience, to herself—into a hollowed out simulation of what it is to be human, to be alive, to be engaged in one’s life. Following the penultimate scene of Jeanne stabbing a client in bed post-sex, the final scene is a punctum: an ending to the nothingness of living. In this miniscule moment decisively selected from the film’s 3 hours and 24 minutes, Jeanne is left in a psychic void identical to the one she inhabited at the commencement of the film’s narrative. Her remove, her silence, her inaction, her repose place her as unchanged, undynamized, unrequited, unresolved. Many viewers of Jeanne Dielman focus their reading on the sociological dimensions of Jeanne’s situation, guided as they are by the scripted dialogue which subtly acknowledges the problematised role and position of women, wives and workers within a supposedly progressive post-war Europe, placing the film in line with feminist consciousness gaining critical traction at the time of the film’s making. Yet this infamous non-ending of Jeanne Dielman arguably supersedes societal portraiture. The film’s performative commentary is strangely nullified by this coda, wherein Jeanne textually embraces her nothingness.

For some, this reading doesn’t acknowledge Akerman as a filmmaker within feminist activism. But is Jeanne symbolically, socially or legally ‘empowered’ by murdering her client, as per standard feminist implication of the film’s desiring politics? Or is Jeanne’s disavowal of her ‘disempowerment’ the source of a nihilistic empowerment that moves beyond the symbolic, the social and the legal? If one watches the film, one can read all manner of positivist sociological affirmation. But if one listens to the film, one can imagine a different realm, where the photographed and performed world is overcome by the materiality of spaces, rooms and environments which contain, withhold and arrange its occupants. The violent ellipsis enacted by Woman Siting After Killing is an invitation to consider this other realm—one where the blunt, obvious, rationalist and realist parameters of filmmaking and storytelling are overwhelmed by the contradictory impulse to acknowledge the meaningless of existence and the unimportance of human life.

The repeated wooden creak audible in Woman Sitting After Killing—here condensed, accentuated, featured and highlighted in the museum experience—creates the sensation of the on-screen room being more alive than Jeanne. The curve of monitors evokes a spatio-temporal stretching, as if a moment from the film has not simply been looped, but rather excerpted as an amoebic life force, forever swelling and contracting through asynchronous rhythms. That wooden creak is an enriched agent of this energy. Like a creaking galleon ship full of diasporic travellers, colonising entrepreneurs or enslaved chattel. Like a Gothic homestead possessed by ghosts, demons, spirits or maleficents. Like the creaking wooden floorboards of a darkened corridor at night, stealthily traversed by entities threatening, predatory or psychotic. It’s the sound heard in Jack Clayton’s The Innocents (1961), Robert Wise’s The Haunting (1963), Robert Aldrich’s Hush ... Hush, Sweet Charlotte (1964), Masaki Kobayashi’s Kwaidan (1964) and Roman Polanski’s Repulsion (1965)—all Modern films that feature chilling neo-Gothic moments of women in houses which seem to come to life by shifting and squirming their architecture to produce creaks, groans, squeaks and rasps. The power of the installation’s sonorum—the domain it creates and evokes through its soundtrack—is how it evidences sound as being an immutable sign of animist energies which operate beyond humanist thresholds.

The opening title credits of Jeanne Dielman is more audio than vision, more sound than image. Almost imperceptibly, a hissing noise increases in intensity. It’s the sound of water in a pot on a gas stove slowly becoming heated and creating a soft aural wash. This sound is then repeated diegetically in the opening scene as Jeanne lights the stove and positions a water-filled pot. It too rises in volume, then is abruptly cut to silence in synch with the film’s first edit to a static mid shot of her admitting a client into the apartment’s entrance corridor. The aural rhythms of Jeanne Dielman in fact are highly orchestrated, conducted and timed in a manner closer to musique concrète than direct sound (in film) or field recording (in sound art). Their occurrence and mixage frame the visual editing; their duration and placement shape the temporality of the visualised activities carried out by Jeanne, her son Sylvain and Jeanne’s three clients. This is to such an extent that the assumption that Jeanne Dielman is a ‘minimalist’ work seems inaccurate. Indeed, the film’s minimalist tenor is closer to the Minimalist experimentation evident in Alvin Lucier’s I Am Sitting In A Room (1969). Over 45 minutes, Lucier’s process tape composition sees him record himself talking of how he is recording himself in a room, and how the room’s dimensions and characteristics colour the sound of his voice within the room. He then plays that recording back in the same room, repeatedly with each new recording, so that the resonant tonal aspects of the room are accentuated to the extent that they engulf the legible speech of Lucier’s words, dissolving them into a ringing harmonic din that is electronic, artificial, unnatural. In a sense, Lucier becomes nothing through being reduced, essenced and transformed into sound. This is precisely what happens to Jeanne in Woman Sitting After Killing: she speechlessly becomes the sound of space around her; her occupancy is sounded.

Standing at Jeu de Palme and watching Delphine Seyrig passively interred in the looping video monitors, I thought of another son-image of Seyrig: as ‘la femme’ in Alain Resnais’ filmed version of Alain Robbe-Grillet’s L’année dernièr à Marienbad (1961). If Seyrig’s Jeanne becomes death through the act of killng and now lives a post-existence, Seyrig’s ‘la femme’ is a textual ghost, a disembodied character whose existence is pure écriture. In Marienbad, she is constructed neurotically by ‘le narrateur’ (Giorgio Albertazzi) who chases her ceaselessly throughout the dizzyingly baroque interiors of a grand resort in Munich, insisting that they had met previously in another luxury spa somewhere in Europe. If Jeanne Dielman is banal and domestic, Marienbad is oppositely ornate and regal. The Jeanne Seyrig cooks potatoes and wipes baths; ‘la femme’ Seyrig flounces in Chanel and poses like a gilded mannequin. If Jeanne is a cinematic exposure of the lowest tier of character-oriented ‘woman’s drama’ through embodied narration, ‘la femme’ is a hysterical concoction of femininity imagined through male-oriented literary conceit. But Marienbad’s photogenic goddess is not simply a matter of erotic pawing and sexual objectification: the figure of ‘la femme’ (crucially disbarred from ‘saying her name’) is an impossible attainment of such obsessive fancy. In other words, she does not exist because she cannot, and she cannot because such an existence resides in the maddening portals of fictional desire. If Jeanne Dielman is a slow-burn gender-reversal slasher movie—emptied of action, tension, psychosis, adrenaline—Marienbad is a convolving de-naturalised stalker movie—emptied of threat, terror, possession, consummation.

Was Akerman using Seyrig to take-down the nouveau roman? To this day, the nouveau roman remains tainted by accusations of it fostering elitist, asocial, depolitical and solipsistic cinema. Depending on your point of view, the movement is a reactionary, privileged dismissal of real-world socio-political conditions and an artist’s remit on responsible representation. Or, the movement’s arch avoidance of such mechanistic signage is central to its ideological point in declaring post-war Europe—riven by occupier collaboration as much as direct warfare—a ‘post-truth’ milieu. For some, this division is further reduced to a generational showdown between old-fart goateed literati, and puckish feminist essayists. Godard and Maoism, the Zanzibar gang and May ’68, Akerman and feminism have formed successive waves to erode the intellectual superiority of the nouveau roman in progressive debates interrogating post-war European cinema. Akerman currently signposts this weather vane shift for an audience whose demand for relevance and identification constitutes the primary metrics for defining both cinema quality and the cinematic experience. But in such a context, might not Akerman’s oeuvre and practice be championed primarily through the gender stance, political slant and social commentary attributed to her productions, rather than via the deeper radicalism of her numerous projects? The most refreshing thing about Akerman is how steadfastly she has grounded herself in formal experimentation, playfully subverting narrative norms not for reasons of heroic rebelliousness, but for a unique and even sardonic grappling with personal vision and how best to energize it through film language. The “Travelling” exhibition at Jeu de Palme was an unexpected place where this option—despite being unannounced or unuttered diegetically—offered a counter narrative to the dominant and popular hagiography of an undoubtedly important visionary in cinema.

Yet a third Seyrig haunts the space of Woman Sitting After Killing: Anne-Marie Stretter in Marguerite Duras’ India Song (1975). The film centres on a group of bored French diplomats in 1930s colonial India, who are administratively and psychologically imprisoned in the French embassy in Kolkata. Torn from their culturally specific bourgeoise trappings, they lounge in the embassy like pulled fleu-de-lis wilting in India’s excessive humidity. The architecture of the embassy’s interiors—softly baroque, alienatingly expansive, elegantly dressed—provides a network of proscenia, porticoes and wall-mirrors, framing the well-dressed attachés and their wives, all of whom are forever moving gracefully between the rooms. Narratively, Seyrig’s Anne-Marie is a central character, but even her positioning melts as the film progresses, as if she is transpiring in a heated realm of dislocation. The structural conceit of the film is ingenious and well-known: the diplomats and their guests talk incessantly, describing details and memories as per nouveau roman stricture, yet as they enter and exit the camera frame, they stop speaking: we only hear their speech as voice-over narration (all credited as voix intemporelle—timeless voics). Thematically, the separation of voice from face manipulates these parading colonial arbiters into vacuous aesthetes and pompous commentators of their surroundings. The sumptuous decor, beautiful costumery and mannered airs of their slo-mo perambulations colour them as semi-conscious automatons in a perfumed purgatory. But textually, their son-image fracture renders them as ghosts of their own circumstance. This leaves Seyrig to portray Anne-Marie as eyes without a voice, and a voice without a face (obliquely recasting Edith Scob’s masked, disfigured character in George Franju’s Les yeux sans visage, 1960). Anne-Marie’s voice is forever ghosted by never being visibly enunciated, yet she is maddeningly tied to the site of her rambling utterances. Indeed, if humans are nothing but the aggregation of their own memories, and humans only exist through being remembered, the sound of the human voice—through its palpable, bi-sensory audiovision—is a prime trigger of sensorial recall. Just as sound throbs in time and space, so does the voice palpitate.

The sensorial tracing of India Song contrasts with the architectonic mapping of Marienbad. The former’s characters reminisce about murmurs, luminescence, fragrances, temperature, querying their recalled experiences. The latter’s characters are literary semes who are animated by their consciousness within the textual machinations of the self-reflexive narrative and its attendant jouissance. India Song is about having once been there in the rooms it depicts. Marienbad is about never having been in the rooms it depicts. Both films, deliberately (and maybe to a fault) drown in the precise, obsessive speech of its characters. For the first 30 minutes of India Song, two female voices often refer to what is seen on-screen or what is audible off-screen. It’s like the unseen women are watching the film the audience is viewing. Who are these women and where are they placed in the narrative? They often describe Indian workers, servants, travellers, itinerants, fisherman, beggars and lepers as a vaguely present Other, disallowed within the confines of the colonial embassy unless via contracted servitude. Interpolated in these environmental evocations are the sounds of weather and nature, and a recurring song sung by a mad Laotian beggar woman. Multiple locations are variously recalled: Kolkata, Bengal, Lahore, Bombay, the River Ganges.

From this point on, the soundtrack becomes multi-planar, combining the voices of depicted characters at a consulate evening function (always breaking into speech just as they move outside of frame) with the chattering of gathering guests (never seen) and occasionally shifts from interiors where bluesy ragtime piano music accompanies the guests (though the visible piano is never manned or performed) to evocative exteriors. These voices become multiplied, all circulating within the orbit of consulate services and internal careerist moves, cushioned by indistinct background chatter, often mixed with the unseen phonographic playback of tango, mariachi and waltz recordings (all by composer Carlos D’Alessio). Anne-Marie is often shown dancing with various beaus, engaged in what seems like psychic dialogue with her silent partners. Their bodies move in time with the music’s tired tempo, but their lips never move. More than once, she strikes a frieze, distracted by something off-screen. At one point she describes her numbed state as “a sort of pain linked to music”.

Near the opening of India Song, the camera in close-up grazes across the burgundy dress to be worn by Anne-Marie. We also see her jewellery, a red hairpiece and other black garments. The image is forensic, as if it is surveying her remains, or the evidence of her existence. Does the film—like all the Seyrig films discussed here—start with her death, be it emotional, psychological, legal or actual? Is Jeanne a re-incarnation of Anne-Marie, or vice versa? Or are they the same person, the same spirit, the same being, each captured in shimmering 16mm amber? Like Marienbad, India Song is absent of foley—of the sound of footsteps, clothes rustling, hand-held objects being moved. In both films, bodies do not exist because they are soundless. These voices are not tied to bodies: they are auditory channels of écriture. As with seminal cine-ghost tales in films like Kwaidan and Herk Harvey’s Carnival of Souls (1962), absented foley characterises the on-screen body as a dimensional aberration, haunting its spatio-temporal realm but never marking it with physical presence. By extension, Jeanne Dielman is a story about a ghost who has become corporeal. Akerman’s everywoman is part-retribution, part-transfiguration. Seyrig embodies this physicality, as if she is versioning her ‘everyghost’ status in Marienbad and India Song.

No wonder Duras surgically operated on India Song to produce Son nom de Venise dans Calcutta désert (Her Venitian Name in Deserted Calcutta, 1976) [2]. In this deconstruction of the former, Duras returned to film the locales and settings—now dilapidated and unadorned—and placed the original, unaltered soundtrack atop the newly edited footage. The audiovisual effect is ravishing in its recontextualized destitution. Just as Seyrig’s ‘la femme’ in Marienbad might be the ghost of a woman who may have been murdered by her husband or another man, Seyrig’s Anne-Marie in Son nom de Venise becomes a completely invisible entity whose voice alone haunts the spaces of her once-living domain. Time has passed, and the rooms have deteriorated, but her voice lingers. Again, this is a woman who has become sound, distilled from the many Seyrigs floating between these films. Son nom de Venise ghosts its host film in the same way that Woman Sitting After Killing ghosts its host film. Each is less deconstruction and more transduction, converting an originating energy—exquisitely embodied and performed by Delphine Seyrig—into the notion of Woman that Akerman observed as trapped in the ‘in-between’ or ‘invisible’ images excluded by conventional narrativity. Jeanne Dielman is a tour de force in its reductivist, isolationist construction of a space for its nothingness to throb on-screen. Woman Sitting After Killing intensifies this, and powerfully sets Seyrig’s Jeanne in dialogue within a critical continuum that highlights the quality of voices, the breath of characters, and how their bodies activate the sound of their space.

Notes

1. “Chantal Akerman. Travelling” – Bozar Centre for Fine Arts, Brussels, March 14th – July 21st 2024; Jeu de Palme, Paris, September 24th 2024 – January 19th 2025. Curated by Lawrence Rassel in collaboration with Marta Ponsa. Conceived by the Palais des Beaux-Arts de Bruxelles, the Chantal Akerman Foundation and CINEMATEK.

2. Son nom de Venise dans Calcutta désert (1976) – first released on DVD (with India Song) in Japan on the IVC label in 2006, and later as part of a Blu-Ray box collection.

Text © Philip Brophy. Images © Chantal Akerman Foundation & respective copyright holders.