Comics, RAW, Topps, Kids & Dinosaurs

Comics, RAW, Topps, Kids & Dinosaurs

published in Art & Text No.33, Sydney, 1989

The past five years have seen many changes in comic culture worldwide. While these changes are too complex and detailed to present here, it can be noted that a certain upwardly intellectual push in comic production has garnered a new respect hitherto undirected at the industry's craft and culture. Three major currents can be cited: (a) the Anglo American trend toward graphic novels (as previously established in France, Italy, Spain and Belgium, countries where comics have always been accepted as a valid form and publishing venture); (b) the successful push (particularly by British comic writers like Frank Miller and Alan Moore) to infuse the super hero and sci fi genres with global commentary, sexual politics, and socio economic analysis; and (c) the cultural mergers and artistic crossovers of American independent publishers like Raw and Fantagraphics, where comics, graphics, illustration and painting are simultaneously confused and celebrated.

But the new comic respectability of the 1980S is not without its suspect tendencies. The 'politically aware' projections of the sci fi or 'conspiratorialist' genres are generally obvious in their scenarios and often tiresomely neurotic about being located within the purile tradition of DC and Marvel super heroes, while the much-touted graphic novel is basically an attempt to extend the comic market into an over intellectualised (and comic-prejudiced) audience by marketing the comic 'object' in bookish avenues of literature. The anarchic energy of comics their anti social drive, their intensity of depiction, their disregard for certain standards in word and image production or language has been overlooked, dismissed, disregarded, and ultimately stifled by their acceptance in a new cultural configuration of art/philosophy/politics/literature, to whom comics have come bearing a changed status and signs of maturity. Fortunately, such configurations have not been overlooked by the spread - part visible, part invisible - of Raw Publications.

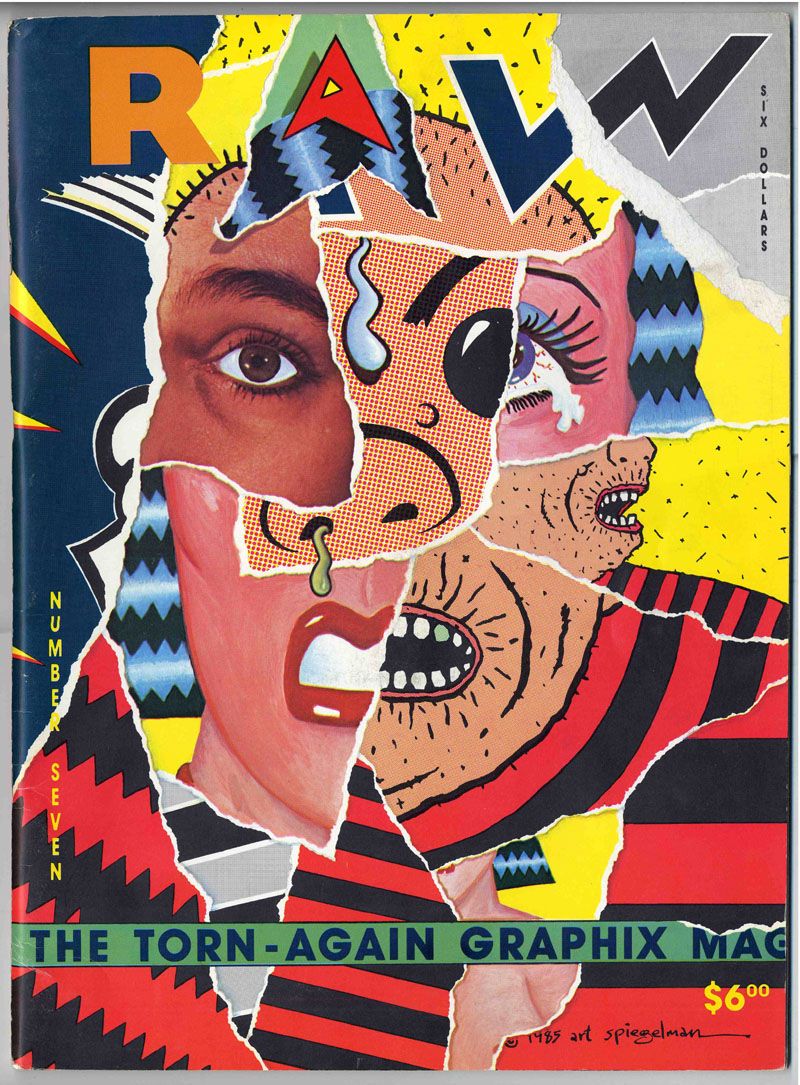

Raw Publications - perhaps the most well known and most influential figure in this contemporary change fit comic culture - was formed in 1980 in New York by Francois Mouly and Art Spiegelman. Since then, Raw has basically set the fine art standards by which many crossover publications (comics/graphics/art) are measured; and while the nine issues of their magazine, plus their set of six One Shot solo publications, consciously steer away from the ambiguous crassness of the comic medium, the work they publish generally embraces the length and breadth of comic history, form and culture, complete with all its aesthetic problematics of taste, value, and meaning. In particular, Spiegelman's 'bipartisan' background (underground and mainstream) has been important in shaping the broader view on comic culture that has enlivened the Raw oeuvre. Between the late 1960s and the early 1970s, he worked in the comic underground scene in San Francisco, and later went on to lecture in comic history and production at New York's School of Visual Arts. Parallel to this, Spiegelman has worked for many years as creative consultant at Topps Bubblegum Company one of the largest swap card gum manufacturers in America.

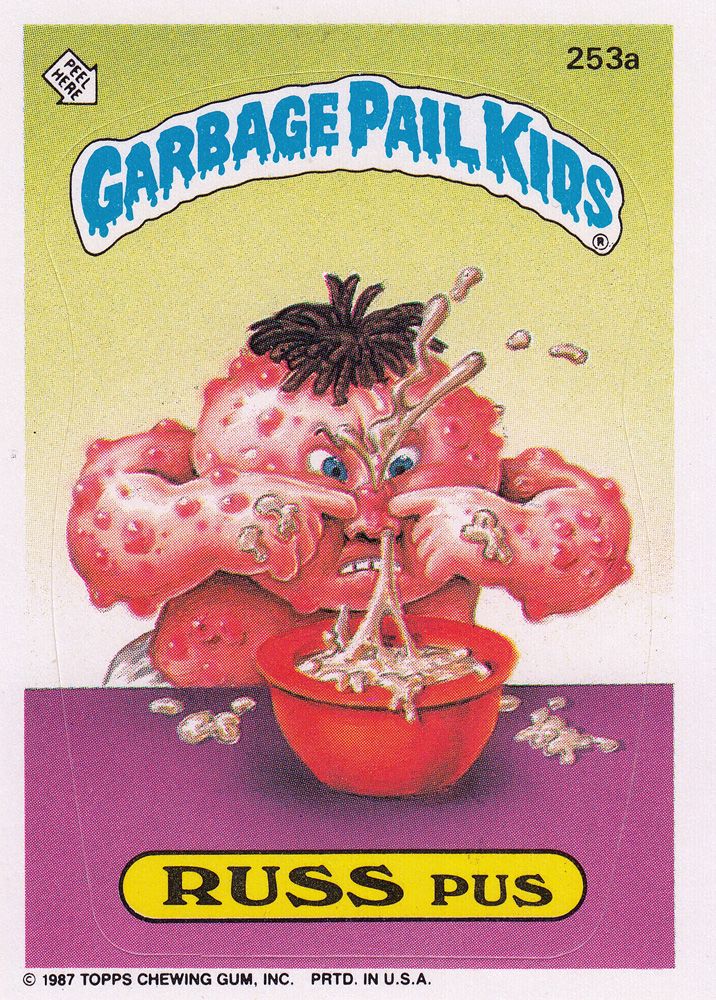

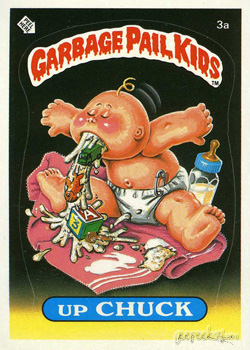

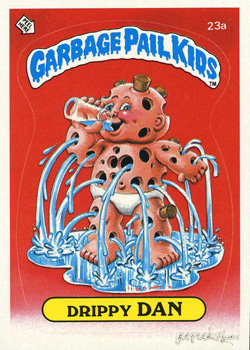

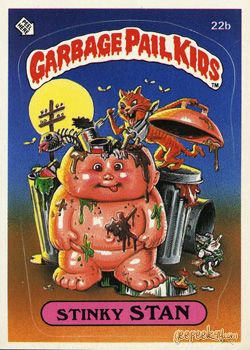

Perhaps the most notorious and best known of Spiegelman's work at Topps is the project he devised with Raw artist Mark Newgarden: The Garbage Pail Kids series, which was a violent attack on the phenomenon of the Cabbage Patch Dolls, designed and marketed by Xavier Roberts. The suspect humanism of such an innocent toy (which you officially had to 'adopt') was brought to the fore when the fad peaked during the 1983 Christmas rush, with scenes of mass hysteria across America as fights broke out in numerous department stores over the dwindling number of these "limited edition" handmade dolls. With their overtly anti social appeal, The Garbage Pail Kids was a huge success among kids in the 1980s, just as EC Comics were in the 1950s and Mad magazine in the 1960s. Spiegelman and Newgarden were deliberately attempting to bring back something that would disgust parents while at the same time appealing to kids a generational gap which the 1970s worked very hard to overcome. The Garbage Pail Kids series attained new heights of grossness, and became seminal to the recent 'gross out' genre of toys (which parents like to label "victim toys").

I would have no qualms in claiming that The Garbage Pail Kids series provides most vital, interesting, and complex sociocultural commentary for the visual arts. The fact that they happen to be bubblegum cards aimed at kids not Only makes the project more confounding or fascinating, but it also prompts one to rethink the political boundaries continually retraced in the area of interventionist image production in both comics and fine art. While 'serious' comics insist on painting political allegories about great 'global conflicts', and bemoan the shifting instability of Third World cultures, they too often end up schematising and sloganeering their messages, not surprisingly, in hyper critical terms. In their drive to achieve the maturity of the adult world, they end up spreading political impotency in the guise of making the reader 'aware' of such things. On the other hand, the outwardly semiotic approach to image production in some contemporary art is ultimately alienated by its own imagery, understanding little of its cultural background and becoming instead a self centered 'artistic' interpretation of what its practitioners speciously label "image codes".

The 'gross out' tactic of The Garbage Pail Kids is more confrontational in its total outlook, mainly because it communicates to the youth market in their terms of ,address. That address is largely incapable of being translated to any other discursive level: these horrific images of kids coming to terms with their own bodies as an expression of adolescent feelings of putrescence and abjection speak volumes on corporeality, sexuality, and the morality of taste. Stich images are reinforced when one remembers that The Garbage Pail Kids are the refuse of that beautiful world deliriously suggested in the 'adoption' and consumption of the Cabbage Patch dolls, whose sex is disguised as 'nature' (babies come from the garden), whose acceptance is overidden by the investment of desire (the dolls adhere to universalising notions of cuteness), and whose identity is erased by socialisation (the child becomes a parent by ,adopting' the doll). The socio political stance of Spiegelman and Newgarden is invigorated by their wide knowledge of comic culture and toy consumption over the past three decades clearly, The Garbage Pail Kids are heirs to the EC brand of horror, and the Mad style of lunacy. In other words, the discourse of these artists is versed in the dialect of their Subject. Nor is their project a one dimensional exercise. The fact that they also produce work under the banner of Raw, with its fine art bias, testifies to the broad base from which they work.

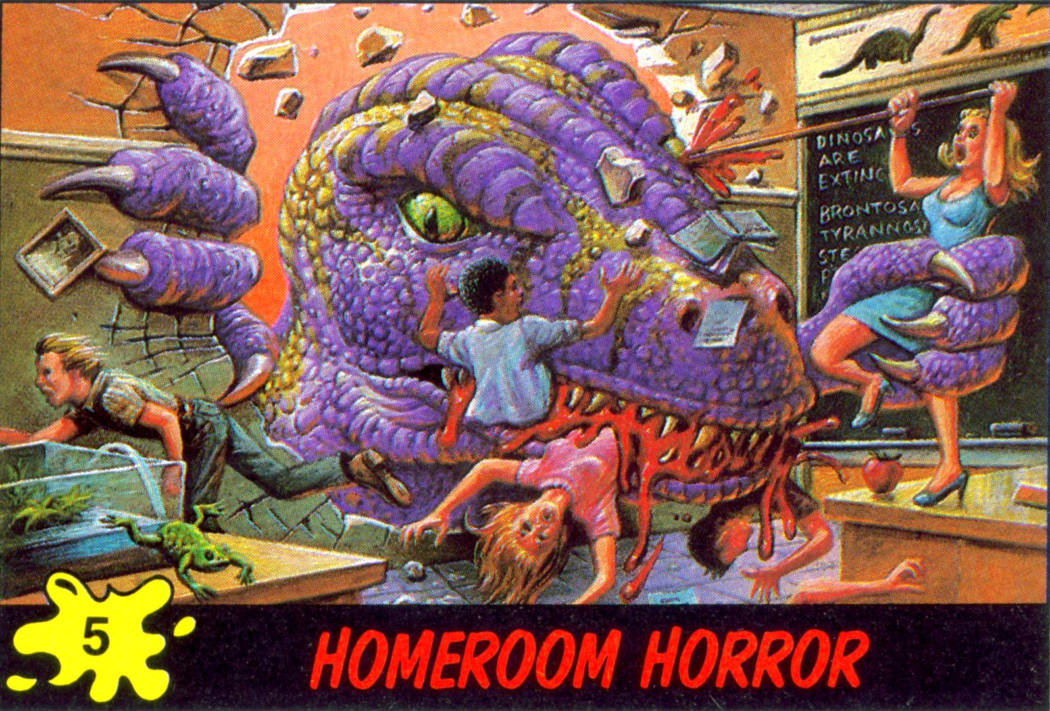

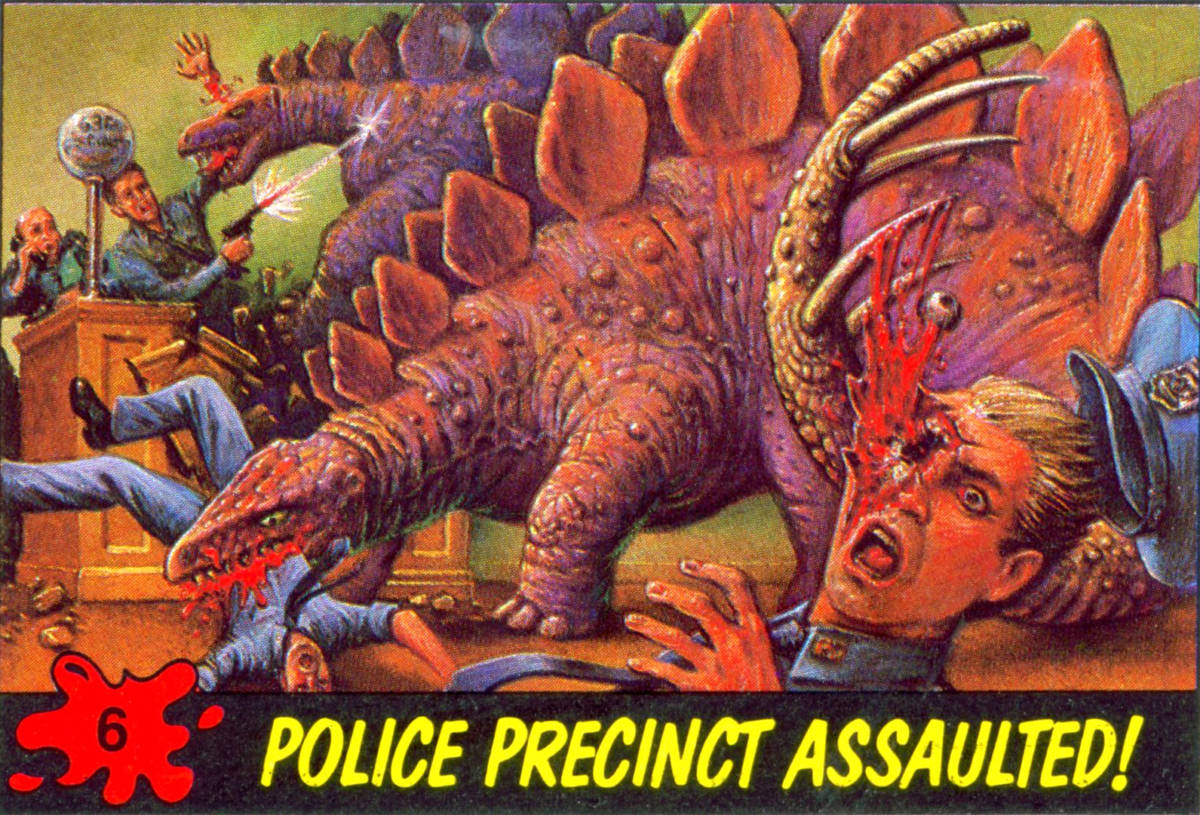

The latest 'gross out' production from Topps is a one off series of swap cards called Dinosaurs Attack! (1988, 55 cards). Though uncredited, Newgarden's work is clearly echoed in the neo Japanese, modernillustration style, exhibiting the same sort of extensive knowledge of comic, toy, and movie history as has Spiegelman. Although Topps is attempting to reach a new and younger generation with this series, it is actually a remake of its infamous Mars Attacks! series of the early 1960s. Basically, Mars Attacks! was a knowing pastiche of late 1950s 'red scare' sci fi movies. The controversy surrounding Mars Attacks! was the result of their graphic depictions of violence and terror, with Martians continually zapping human beings: the series shattered almost every social convention and political belief of the time.. The cards very quickly met with resistance from distributors and proved financially unsuccessful, repeating the fate of EC Comics and certain issues of Mad after the introduction of the paternalistic Comics Code in the late 1950s (a self regulating Board within the comic industry able to exert pressure on distributors to carry only material that would not cause bad publicity for the industry).

The success of Dinosaurs Attack! is more guaranteed because it plugs into the current popular fixation with dinosaurs, best demonstrated by the huge success of toys like Dino Riders. Like most instances of horror in media entertainment, the Dinosaurs Attack! series portrays the more repulsive and adverse aspects of our societies, attracting dread and awe as its stories are located on the fault line between the acceptable and the abject. For example, three major social institutions are attacked in vivid pictorial detail before the series reaches its tenth card: Homeroom Horror (No. 5) shows a teacher torn in half by an Allosaur while she is setting homework on the history of dinosaurs; Police Precinct A ssa tilted (No. 6) shows that institution being stampeeded by a herd of Stegosauri, while a police sergeant gets his eye ripped out by one of their spiked tails; and D.C. Holocaust (No. 7) shows the White House being demolished with the first lady and her C.I.A. attache being masticated by a flock of Pteranodons. The cynicism of these scenes is highlighted by the narratives on the back of the cards, laid out like front page headlines. As the series progresses, one begins to wonder what respected institutions remain to be demolished. The wonderful irony of the cards is that they always give factual information oil the habits, dimensions, and lineage of each species of dinosaur just the thing to placate teacher and parents alike. (Moreover, the heroes in the serial are a small girl and female scientist, while the scientific experiments are directly attributed to monetary greed.) But apart from the implicit positivism of such a scenario and contrary to the usual pedagogical function of most 'progressive' toys these cards fully demonstrate the antisocial drive upon which all comic history and culture is founded. Their gross character is their grace.

But is it art? Of course not and that's precisely why the cards are so powerful. Not that Spiegelman, Newgarden, Raw or Topps take a reactionary or revisionist anti art stance, but that works like The Garbage Pail Kids and Dinosaurs Attack! generate culture for a populace to whom art is of little concern. The success of these cards in popular culture based on a transcultural concept of art , aesthetics, sociology and mass media is something to which the museographic intentions of fine art and the pseudo political designs of contemporary art can only aspire. While various Raw artists (like Sue Coe, Gary Panter and Charles Burns) have also become exhibiting artists, producing a set of conflicts which will make their work over the next few years even more interesting to watch, one suspects that the Topps cards like their predecessors in social satire, EC Comics and Mad will be hard pushed to find acceptance in legitimised cultural spheres. Their base appeal, however exploitative, is a threshold which to this day despite Al 'popular culture, 'mass media', 'working class' and 'low grade' post Pop proselytisations art has not managed to cross.

Text © Philip Brophy. Images © respective copyright holders.