The Tyranny of the English Voice in Anime

The Tyranny of the English Voice in Anime

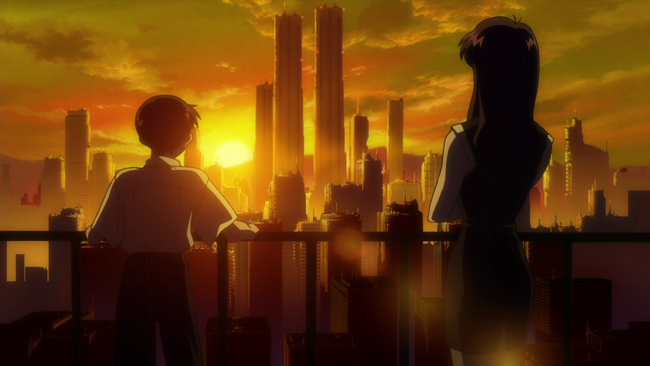

Neon Genesis Evangelion

published in Real Time No.31, Sydney, 1999Way past midnight, the TV plays an old movie. I'm in the kitchen working. The sound of the movie is heard in the distance. It's a melodrama - a 'woman's picture' from the 30s with Joan Crawford. I savour the soundtrack: the thickly compressed duco of its arcing violins, occasional sound effects and - most of all - the breathless dialogue. It's still the 30s: films are 'all-talking'. Not simply because dialogue is important due to cinema's centralization of the script as a sanctioned authorial fountain, but moreso because lip-synchronization was the holy grail which film technology had sought since the end of the preceding century. To join speech seamlessly to the enunciation of the written word was and remains cinema's lofty enlightenment. This would be repulsive enough by itself, but fortunately the energy which fuelled this drive was the sound of the human voice. It is not unreasonable to claim that the Hollywood star system from the dawn of sound to the dawn of television feted the voice as much as the face. Garbo, Cagney, Monroe, Grant, Hepburn, Wayne - their voices are as readily recalled as their faces. The sexy sound of 'classic' Hollywood comes from erogenous larynxes which performed the wordy scripts hammered out on sterile typewriters manned by a thousand uptight Barton Finks.

Just as I am charmed by the unlikely marriage of captivating vocal performances and over-written scripts in old Hollywood movies, so am I repelled by the post-dubbing of the most popular trans-English form of cinema/television in the 90s: Japanese animation. How often have I recommended an anime I know in subtitled version to someone who then encounters it as an American or English dubbed version. Needless to say, most dismissive views of anime are founded on the atrocious use of bad American and English actors who sound worse than footballers and phone sex workers at an office Christmas party. Yet, I remain mystified as to why I think the original Japanese versions sound better. Am I a snob? Do I like practicing my Japanese? Can I speed-read subtitles? Well, yes to all of the above. But whilst watching a Ninja fly through trees and shifting dimensions as a nuclear ball hurls toward him, I hate the way I suddenly get the image of a San Francisco computer salesman at a basketball game. Never has the American voice sounded so prosaic, flat and dumb than in dubbed anime. And despite the deafening iconic presence of the American voice in so much media, never has it sounded so out of place as it does on the Japanese soundtrack.

Hideaki Anno's TV series Neon Genesis Evangelion (1995) has a soundtrack that is so Japanese it will be decades before Occidental forms of audiovisual entertainment begin to successfully mimic it. Not only does Evangelion have many memorable vocal performances (Shinji, his father Gendo, the other 'children' Rei and Asuka) but there is a total logic to the sound design which both typifies its 'Japaneseness' and qualifies the role of the recorded voice within its aural netting. In fact, it should never be forgotten that 'sound design' is the creation of a sonic logic wherein all elements are orchestrated in accordance to our peculiar and precise understanding of how an imagined reality would acoustically operate and psychoacoustically resonate. To understand how any one element - a voice, for example - appears, happens and/or is rendered in a narrative form, one must wholly investigate the narrative's sonic logic. Neon Genesis Evangelion exemplifies 4 primary categories of audiovisual narrativity which define the sense of its soundtrack: mecha design, musical eclecticism, spatio-temporal rupture, and emotional compaction.

Mecha Design

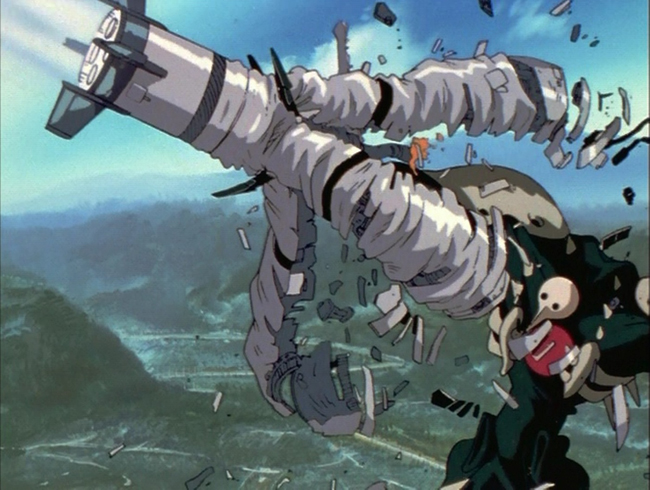

The design of mechanical devices and machines - known as mecha design - is an important area of pre-production in Japanese entertainment. In manga and anime, objects are imagined, envisaged and designed as if they have to be used. That is, their logic is based less on their 'look' (a very Western notion that joins DaVincian optics and modernist sensibilities) and more on their tactility. Virtually all Japanese design promotes an erotic relation between user and machine, between object and hand, between shape and body. This pervades everything from a Kawasaki motorbike to Sailor Moon's skirt. Most importantly, the 'look' of objects in Japanese design is accepted as a separate and auxiliary aspect of the objects' purpose and function. Bank machines can be based on the look of tomatoes; skyscrapers on milk cartons; cars on deep sea crustaceans; perfume bottles on carburettors. They each will do what is required of them, so there is no real reason for them to speciously prove their existence through their look. (This is but yet another aspect of the 'calligraphic' in Japanese culture, where an image or a look is embraced as pure visual substance with no referent to the real.) The design of machinery in Japanese manga and anime is therefore a prime textual layer in the many futuristic scenarios wherein man and machine exist in a complexly modulated harmony. It is no surprise then that Japanese sound designers for anime obey the logic of the mecha design, carefully analysing issues of weight, density, force, energy and mass before they even start to imagine the acoustic and transmissive properties of the machines.

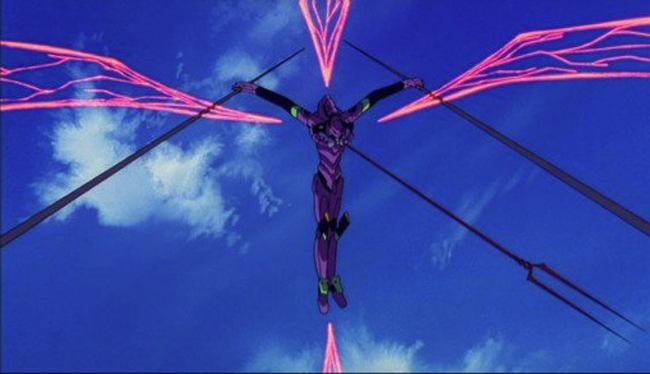

Neon Genesis Evangelion features such a sharply defined sense of acoustic design by Toru Noguchi (in dialogue with director Anno who is also one of the key mecha designers of the series). Firstly, most of the human machinery is connected to either one of two places: the city of Tokyo-3 (a spread of 'armament buildings' which retract underground when the Angel invasions occur) and the headquarters of NERV (based underground in a 'geo-front' complete with artificially maintained land, water, light and air). Simply, all preconceptions of difference between inside and outside, between stasis and motion, between base and apex, between form and ambience no longer operate in such a city of the future. Accordingly, acoustic ecology, industrial compression, noise pollution and aural atmosphere operate under new logics and codes. Secondly, each of the Angels (the diabolical threat to Earth) has their own look and an equally distinctive sound. This is especially noticeable due to the design of the Angels whose visuality references a series of modernist and ancient archetypes of biomorphic form - from Aztec wall paintings to Miro's murals to Donald Judd cubes. Amazingly compounded sound effects accompany their terrible force, based on the power of violence they unleash on Tokyo 3. And despite the problem in designing sound for such impossible imaginings, an effective 'mismatching' of unexpected sounds with unexpected forms/shapes/beings runs throughout Neon Genesis Evangelion. And thirdly, Shinji and the other 'children' operate their Evas (giant robots) by being inserted into the machines via a liquid-oxygenated capsule which psychically links their nervous system with the Eva's sophisticated robotics. Sound is bound to behave differently under such conditions, and an awareness of this governs much of Evangelion's sound design.

Musical Eclecticism

Now if the acoustic and psychoacoustic world is turned inside-out as it is in Evangelion, it is entirely appropriate that a musical eclecticism prevails. Japanese anime has consistently offered alternatives to the Wagnerian leit motiv approach to serially repositioning a melodic refrain or theme throughout a film score. While this approach has typified both romantic and modernist film scoring, anime employs a string of motifs which effectively cancel each other out - or at least render their significance fluid and unfixed. Americans have often commented on how the Japanese place their music cues in the 'wrong' place - as if George Lucas and John Williams control the universal imagination. The use of New Jack Swing in Blue Seed (1995), Electro-Ambient in Please Save My Earth (1995) and Prog Rock in La Filliette Revolutionaire (1997) as score rather than sourced songs further typifies this seeming 'wrongness' about anime. The European orchestral machine is employed in anime for pure effect - not because 'that's how movie music should sound'. Further, there is usually no governing or determining style in any one anime. Shiroh Sagisu's score to Evangelion at varying times sounds like The Thunderbirds, FM-soft rock, Steve Reich and Ken Ishii. but the result of this eclecticism is not arched, strained or postmodern: it simply mutates and evolves in response to the surges and pulsations in the location and dispersion of dramatic energy.

Spatio-Temporal Rupture

While the score to Evangelion seems to simulate a radio station programmed in a chaotic random fashion, there is a purpose behind such chopping and changing. For the future in Evangelion - like the post-apocalyptic continuum which paves the way for Japan's unsettling existence - is on the brink of destruction, and all that is calm is merely the potential for radical destabilization. Spatio-temporal rupture thus rages throughout Evangelion. Often we are caught in the claustrophobic mind of young Shinji as he grapples with an aching existential dilemma of how to live alone, divorced from social and human contact. The screen will go black, white, or assault the eye with Pokemon-style strobe-cutting; radical shifts in sound density will accompany these visual ruptures. Silence screams and pierces the soundtrack; detonations capitulate to a soft roar; all energies are continually inverted and reversed to complement and counterpoint their dramatic weight. Sometimes complete sections of plot disappear to convey Shinji's loss of consciousness inside an Eva. Sometimes his psychic sensitivity teleports him unexpectedly to ill-defined locales and spaces. The musique concrete collage of sounds and atmospheres which play with these spatio-temporal ruptures is never gratuitous. If the sound design - like the music - in Japanese anime sounds 'wrong' it is not simply because we aren't listening carefully enough, but that we are not cogniscent of the way that Japanese sound reflects narrative, rather than neutralizing it as does Western audiovisual entertainment.

Emotional Compaction

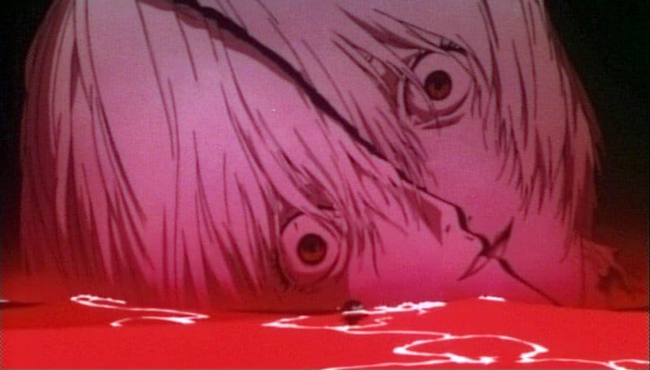

A postwar cliche of the Japanese - in American eyes - holds them as being 'inscrutable', as if they are strange aliens who behave suspiciously in ways we do not understand. This, of course, is both their power and their continual threat to the hegemonic Euro-forces which have shaped our ways of thinking, seeing and hearing. And as their society is impenetrable, so is the very concept of 'drama' - pathetically universalized by the western intelligentsia as they lick the butts of Grecian philosophers - unworldly in Japanese entertainment. Not that Japanese characters behave 'differently', but that the schisms which we perceive as corrupting and interfering with a character's identity are acknowledged as the substance of a character's identity. In the West, we will crudely designate the hero, the buffoon, the cynic, the sage, etc.; in the East, characters are founded upon their schizophrenia, established through their multiplicity, and defined by their inability to be grounded. Evangelion's characters - especially the three 'children' who complexly represent Japan's own problematized Generation-X - are formed by means of emotional compaction. Joy harmonizes grief; suffering prompts laughter; compassion folds violence; hatred suppresses innocence. Evangelion's characters are quintessentially good, bad and ugly. Music, sound and voice dance in intricately orchestrated lines that map out these characters not as containers or vessels of emotion, but shimmering and shifting apparitions of emotional complexity - not 'rounded out' by authorial conceit, but unrefined as befits the prickly irrationality which dictates our everyday exchanges.

Now, having very briefly outlined some issues of mecha design, musical eclecticism, spatio-temporal rupture, and emotional compaction and how they impact upon the sound design in Neon Genesis Evangelion, consider the presence of an American voice in the midst of its non-Western sonorum. All the finely-tuned relationships between score, spot-effects and vocal performance are jettisoned by actors who - trained in the Western theatrical/dramatic tradition of naturalism - would probably neither understand nor agree with anything I said above. American post-dubbing is woefully exaggerated as the actors reinterpret the emotional schisms of Japanese characterization as aberrant and illogical. Western post-dubbed performances always sound devoid of context: the American voices unconvincingly enact and narrate a scenario which is beyond their comprehension, while the English voices pathologically expel a smarminess which polarizes the worst cliches of nobility and decrepitude.

Even though SBS-TV has screened the embarrassing dubbed-version of Evangelion, there is an opportunity to encounter the complete cinesonic experience of the series thanks to the release of the subtitled edition by Siren Entertainment. Granted that most people probably hate reading subtitles, those who are intrigued by sound - and those who are genuinely interested in immersing themselves in the audiovisual 'inscrutability' of anime - are encouraged to experience Evangelion in its original format.

Text © Philip Brophy 1999. Images © Gainax