The Truth Of Sound

The Truth Of Sound

Contact

published in Real Time No.24, Sydney, 1998In a world where sight is clung to in desperation to prove the existence of things, the validity of sound will always be suspect. The law may rely heavily on words, but only through recourse to its power of recording the spoken. And the law mainly wants to hear the words of eye-witnesses - those whose sight can be encoded through words for proof of existence. Ultimately, sounds and images are equally circumspect in their convolution of information for the auditor-viewer. And so it is with cinema. Each modulates the other to compound the experience: images confer with sounds, sounds defer to images. When visuals openly declare themselves, they do so with surreptition; when sounds boldly project themselves, they do so through refraction. Restlessly shifting between base linguistics and impenetrable phenomenology, the truth factor of cinema is as indigestible as so many laws. It hides away, beamed from a sound-proofed bio-box, distributed through invisible speakers. In the cinema, neither medium, form nor any dialectic juggling of the two will grant audio-visual absolution. Such is the beauty of living its many wonderful lies.

This talk of cinesonic truth is not as obscure and unnecessary as it appears. Sound designers the world over act like attorneys of the sonic. They encode sound in order to prove existence of events, actions and spaces, working to ordinances of legibility, plausibility, believability. Every sound they attach to an image lies "I come from this image". Every sound they erase from an image lies "I am but image without sound". Most films cannot bear the weight of their own falsehood. Their legitimacy evaporates the moment their audio-visual activity occurs, sucked into a smokescreen of artifice which attempts to have us believe that cinema is a knowing theatre of stylization. All cinema knows is that it cannot tell any truth - yet cinema rarely can accept that it is actively lying when it tells its story.

In Alain Robbe-Grillet's inquiry into truth and fabrication, L'homme qui ment (1968, The Man Who Lies), the validity of image and sound are equally questioned, interrogated, disproven - then accepted. From the film's opening barrage of off-screen gun-fire causing a staged death and return-to-life, to the film's closing of a draw containing multiple copies of photos which incongruously 'prove' the impossible lie Jean-Louis Trintignant has been spinning throughout the story, L'homme qui mente fondles and fingers the lining between sound and image, between the spoken and the witnessed, between the suppressed and the imagined. Typical of French jouissance and its slide from textual deconstruction into onanistic gratification, the film revels in the charade of role-play and its correlation to sexual games. In sex, all from of fakery is acceptable if pleasure can be mobilized, generated and sustained. That wig, those shoes, that implant, your voice - all lie to produce an undeniable and implicitly true effect. In greater accordance with artistic pretention and ontological presumption, Michael Antonioni's Blow Up (1966) throws up a pasty, intellectualized pondering of erotic and psychological truth via the highly unimaginative metaphor of the camera lens. Brian De Palma's aural revisionism of the film in Blow Out (1981) may foreground the sonic, but only under terms of visual mimicry where sound technologies stand in for their visual precursors. Despite the polarities of the films' mode of address - fetishizing either lenses or microphones - they concur in their reinstatement of a truth presented with all the hollow pomp of barristers.

Many films feature courtroom scenes where the truth is used as a driving principle as desperately as cinema denies its ability to deliver that very truth. In fact, too many films feature courtroom scenes. It's a cheap tactic for a desperate audience. Robert Zemeckis' Contact (1997) climaxes with a courtroom scene. But it does so to quell the mania for validity - to posit issues of belief as epicentral to the dissolution of truth-seeking mechanisms, technologies, institutions and dogmas. And it does so with a sharp awareness of the formal contract it must take out with the cinesonic in order to achieve its post-truth ideal.

The title Contact evokes legal process. Did you have contact with X? Was X aware of Y through your contact? When was contact initiated? When did it cease? In the law, contact implies awareness, in much the same way that sight impels confirmation. In a wider sense, contact facilitates a joining of realities, from infected bodies to psychological motivation to spiritual conversion to extraterrestrial life-forces. Contact opens with a visualization of much that we could never see, but most of which we have culturally and historically been privy to. What at first appears to be a gratuitous computer-generated track through space is actually an astronomical journey through sonic time capsules, dotted across outer space in a line which documents the moments of their emission. Like listening to a hundred radios broadcasting from ulterior and unsynchronous time lines, a wash of song and noise is jettisoned through the screen's frontal zones and spurts into the rear surround sound field (one of many vibrant and scintillating sonic collages by Randy Thom which defines the unworldly sound design for the film). The direction of the dynamics becomes clear: we are travelling not into outer space, but from outer space. Our audio-visual perspective is that of an extraterrestrial who has by chance encountered the trajectory of our reckless and random data transmission throughout time, summarizing a history of broadcast and recording technologies. As with so many technologically astute contemporary films, the cinesonic spectrum is used to invert audio-visual relationships as key leverage for proposing the realignment of cultural, textual and even mystical precepts. This scene is a suggestion not of whom we as central beings are in contact with, but who from beyond is contacting us.

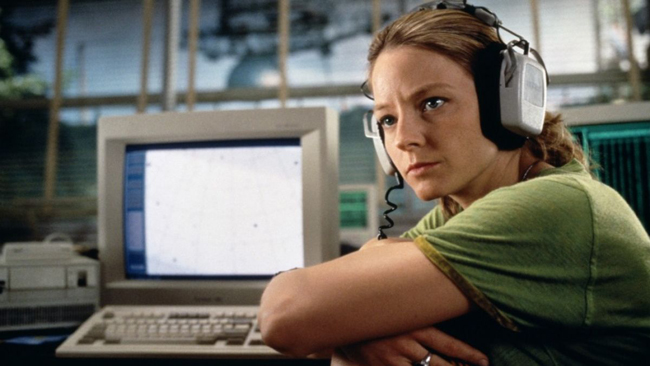

As comfortably centred characters, David Hemmings in BLOWUP and John Travolta in BLOW OUT go about their daily routines until their process of recording is interrupted by the unintended presence of data which provokes them to seek out a truth of which they are no part. Visuality and aurality, respectively, are the matter of their encoding, the rendered textures with which they create illusions. Contact's central figure, Ellie Arroway (Jodie Foster) is literally light years beyond the pithy, planetary modernism of Blow Up and Blow Out. From the beginning, she is searching for something - an unjustifiable existence which she cannot see - and is thus an active figure, less concerned with the remote rendering of things like models' bodies and women's screams, and more concerned with the remote possibility of other forces outside of herself. Crucially, she is not interested in encoding a past event: she scans the airwaves in the present, fishing for sonic signals which intersect her moment of seeking across radically displaced zones of time and place. She replaces the camera and the microphone - instruments behind which the in the encoder hides - with radar. She does not wish to 'find out' something; she wants to find something - directly, unmediated, unconditionally. If astronomical charts map what exists where, Ellie's obsessively pin-covered charts map what might exist but doesn't reside there. While the archaeologist (and all his symbolic brethren who populate the cinema) visually confirms existence through remnants of the past, the astronomer aurally sifts through the potentiality of existence in the present.

Many rich images in Contact affirm this, as Ellie closes off her terrestrial world while plugged into another realm, erotically lulled by a continuum of noise spiting through her headphones. Just as her cosmological maps of grow in scale and density, so too do her ears: from a single set of headphones to the earth-shaking scene when she commands a phalanx of gigantic satellite dishes to rotate in synch with her as she rushes in a pick-up truck to confirm the location point of an extraterrestrial sonic emission. When she finally makes contact, a dimensional pulsation grows which totally re-territorizlizes the cinema's auditorium. Through deft frequency manipulation and gorgeous spatialization, the sparkling harmonic sound conveys the presence of something which exists beyond that which is presumed to be the narrational space and its fictive zoning (an artistic strategy Thom defined in Dennis Hopper's Colors, 1987). As auditors, looking at a spectral analyser with its pumping LEDs while hearing this sound, we occupy the fused headphonic/radarphonic space of Ellie: a primed and imaginative place where the desire to hear external presences creates the net wherein signs of the beyond can roost. Here is a profound moment of cinematic truth: surround sound activity (far more lively and kinetic then the dry notion of "off-screen sound") captures all that the screen cannot show. If we are to contacted by something beyond, it is likely it will first make us realize the limited recording range of both our mental facilities and monitoring technologies.

The complex phenomenological and technological ramifications of Contact's hypothesis warrants further in depth discussion. It is a first (especially in Anglo-American live action cinema whose mystical rigour trails decades behind Indian musicals, Japanese animation and Hong Kong action movies) in employing surround spatialization not merely for Judeo-Christian mystical spookery, but for the investigation of how one shifts from a centred existence to a decentred one. Despite the knee-jerk reactions by many hip pseudo-non-believers who deep down fear the mythology of God, Contact's mystical pondering is broad enough to not be thematically rooted in either religious or humanist dogma, and open enough to state the vitality of sound as a life-force whose energy fields and physical expansiveness effect us deeply despite the thinness of our ocular rationalism.

Text © Philip Brophy 1998. Images © respective authors