Some notions. Some points. Some examples.

published in Interventions Nos. 21/22, Sydney, 1988expanded slide lecture - George Paton Gallery, Melbourne, 1990; Alberta College of Art, Calgary, Canada, 1990

Some Notions

Physicality

Height - 5'10"; weight - 180 lbs; neck - 17"; chest - 47"; biceps - 17"; forearm - 14"; waist - 32"; thigh 23 & 3/4"; calf - 16 & 1/4". They are/were the 'peak' statistics of Charles Atlas, probably the most well-known body-builder of this century. His mythical biography is documented as part of America's folklore (the Dream personified, etc.) to such an extent that the above statistics are on file in the New York Public Library and hermetically sealed in a vault in Georgia's Oglethorpe University. For sure, Atlas' notoriety is partly due to his existence as an ideal form and shape (the aesthetic quest of physical culture, the culturing of one's body), but his place in cultural history is more determined by how he objectified his body ; how - through the help of his business partner/ex-ad man Charles Roman [1] - he sited his body as an ideal in and of itself, as the (physical) fusion of the means and the end to the desire to "look good - feel good - be good".

His chosen moniker "Atlas" proclaims classical aspirations, but it also reveals the desire to map out one's body as a terrain, as a place for concentrating energy. Defined by finite parameters, his life was accordingly statistical : a progression from one numerical summation ("I was a 97-pound weakling") to the above set of 'perfect' co-ordinates. Atlas' self-objectification itself is ideal, able to be summed up in any form - from its time-capsule essentialism to its abstract rendering as enlarged benday dots on the back pages of comics. Strength, vigour, style, vim, health, composition, power - all are circulated and redistributed around, within and across the body as a physical place ; a place of physicality.

Bodily Contact

As has been pointed out by Adrian Martin in his "Bodies In Question" [2], most popular and predominant recourses to discovering the self (and/or its other) through numerous modes of bodily interaction are suspicious and questionable in their construction of 'you/your body/the world' homologues. From philosophical projections to scientific models, the body is a highly problematic site for theorizing our affects upon and effects from the world. But what if a different major social drive is posited - not the centralized quest for truth per se, but the plain desire to 'touch' physicality ; to locate places of physicality not as proof of the real, but as instances wherein we can acknowledge the experience of touching as evidence of our capacity to be through feeling.

As this somewhat clumsily yet carefully worded concept implies, the actuality of a given 'truth', its empirical presentation, its rational explanation, and its physical impression on our physical bodies are all secondary to the primary acknowledgement. The touch, the flesh, the body are then not just cultural metaphors or experiential facts, but also phenomenal agents in the realization of our existence through our bodies. Not only may we pinch ourselves to prove that an experience is real, but we may also reinterpret that act as a gesture, a process, an image, a tool for some proof of the act and state of experiencing, of feeling, of being. Virtually any form of fiction, hokum or voodoo can grant us this kind of non-physical experience of 'bodily contact'. Its qualification can be varied and multiplied - from electronic media saturation, to social/cultural simulation, to ideological power controls - but its status as desire indicates not how we might understand our bodies but how we might use our bodies to understand ; how we might identify body shapes, surfaces, forms, presences as indicators of physicality, of a 'phantom-tactile' relation to the world.

If we view the rampant body-ness of contemporary times (horror genres, health fads, machine-men toys, dance music, etc.) in this way , an assimilation of those bodies' meanings and effects would then be dependent on recognizing a new use value for and of bodies ; a use value which would constitute an objectification of the self 'into' the body in the manner of Charles Atlas. In pragmatic terms, body presences (in media, art and entertainment) need not be 'about' the Body, and nor should usages of one's body necessarily propose a dialectic between it and the world.

Body Principles

The contemporary horror film (post 1978) has been the major accentor of such a consciousness of bodily contact, not simply in how the films work the body as image, object, sign and symbol through photographic and cinematographic modes, but how the genre as a whole has recently informed other areas of the cinema. To give a brief example before we start detailing effects : if one views Flashdance, Rambo and Transformers as horror movies (by their fetishization and manipulation of the body), one can see that what was presumed to be directed at the body could perhaps be - either oppositionally or simultaneously - projected from the body. This is then reversed in The Keep (1985) where the `monster being' is, simply, a `monstrous human body'. Such semiotic transferrals - what we could term `signage in motion' - illustrate how complexly genre is operating today ; how genres can feed off one another in those myriad fold cracks which thematic, iconographic and symbolic readings cannot seal off. Pertinent to our concerns with the body here, the above brief example of semiotic transferral or generic mutation leads us to two dominant ways in which the body is fetishized and manipulated, and which we can term 'body principles' : Explosion and Expansion.

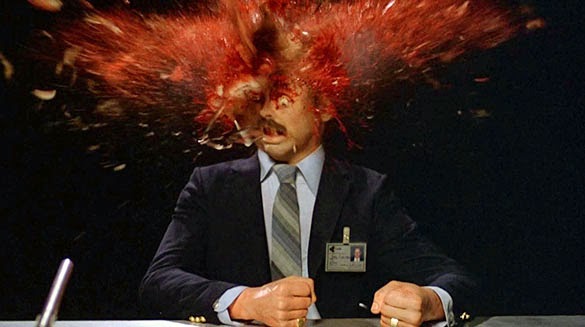

Explosion

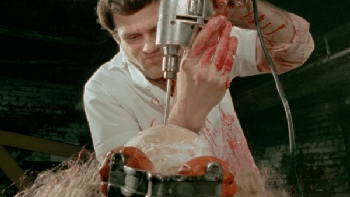

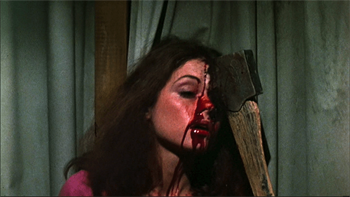

Explosion is the directing of concerns, fears, frustrations at the image of the body, causing it to splatter under force, impact, intensity and pressure. More so, it is the point of eruption, the instant of dematerialization, that serves as the dead-end-centre for the painful yet pleasurable build-up of everything being directed at the body - both material and symbolic. In bluntest terms, the photographic effect of the exploding body or body-part is not unlike a cum shot. The Explosion is thus the theatricalized catharsis of savaging the Self, maligning the Other, and generally terrorizing all those touted symbolic codes. [Special-effects for Explosion : charges, triggers, timers, etc.]

Expansion

Expansion illustrates similar concerns as coming from the body - seeping, inflating, enlarging, reforming ; causing it to crack its surface, shed its skin, reshape itself. The intensification of Expansion is all that leads up to the Explosion : all the transmogrification of wholes, all the stretching of limits, all the mutated erections of recognizable forms and textures. The body, as such, is kept intact, kept material, kept corporate, and thus disallowed its excessive climax. This is not coitus interuptus or masochism, but evidence of the body as container of all energy, as mainspring for all desires motivated by those concerns directed at the body-image in processes of Explosion. [Special-effects for Expansion : bladders, valves, pumps, etc.]

In terms of genre, we find that whereas Horror movies nearly have a monopoly on the Explosion principle, many non-Horror movies employ the Expansion principle. The space between these two principles - never fixed - is the netherland of sub-genres; the genetic wasteland of Freudian case-studies. Sexual organs are de-eroticized (Marilyn Chambers' protruding phallic injector from her armpit in Rabid, 77) and tools of violence are eroticized (Sylvester Stallone's humongous blast-charger in Rambo, 83). The permutations are endless - signposted as such by the memorable neck-stretch/head-crack scene from The Thing, 1981. More often than not these permutations truly are arbitrary configurations and serial conglomerations which tend to make psycho-analysis of the resultant images frustrating and even futile. However that very frustration and futility is the key to understanding the nature of all this body imagery, in that they are not manifestations of psychological impulses which await our individual identification through their implicitly, but rather fictitious possibilities of an unqualified textuality awaiting our individual consumption of their absurdity. (This does not suggest that psycho-analytic frameworks are impotent, but if they only service wildly convoluted symbolic flows - or, worse still, predictable readings (like the many performed on Aliens) - one should perhaps check their appropriateness for a cinematic production which delights in textual chaos, symbolic confusion and an overload of what I have elsewhere termed "possessed signifiers" [3] - where `meaning' is demonically possessed by `effect'.

Disembodiment

The above principles are presented so as to extend relations and analogies between technique, image and effect, based on the notion that (again, like Atlas' body) everything can be fused in the one place of physicality. In film, that one place is the cinematic scene where set-up, event and symbolism come together to simultaneously exploit, understand, interrogate and comment upon the body. This simultaneity of measures and concerns is not so confusing when one accepts the premise of desire here - the desire to experience a form (phantom, material, physical, symbolic) not of the body, but of that 'bodily contact'. It is a desire that finds fascination in being stimulated, repulsed, engaged and assaulted by representations of body-ness ; a fascination with disembodiment.

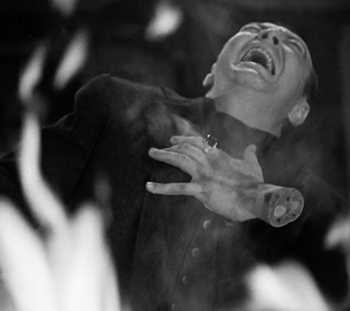

'Disembodiment' is intended to signify an emptiness of body : not the finality of a corpse or the spirited evaporation of 'the soul' to another dimension, but the presence of emptiness. It is an emptiness wherein neuroses and psychoses are rendered immobile and are incapable of providing the motor mechanisms for all the cathartic releases and Freudian undercurrents which figure as fuel for classical, gothic and modern horror. It is an emptiness which connects with our emptiness as vessels for the contemporary horror film, where pleasure is generated by a certain detachment from and bemusement with the saturated effects of the genre's history, and where knowledge of our own bodies is infused in the unworldly logic of the body's terrain on the screen. This is, respectively, how the most vile and savage of films can fully retain their intended comic effect, and how medical procedeures and observations can serve as contemporary horror scenarios [4]. Our bursts of laughter at scenes of dismemberment and disembowelment are tangent to our perception of the screen's non-bodies, as are our rushes of adrenalin tandem to our imagination of our own bodies. We are - it is likely - not lost souls but disembodied selves whose essential relation to the body (ours/theirs) is empty and void. Surely if we can divide, multiply and rearrange our 'selves' could we not do the same with our 'bodies'?

Some Points

Erotics

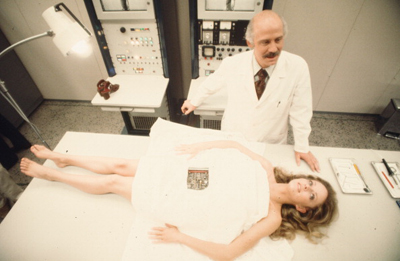

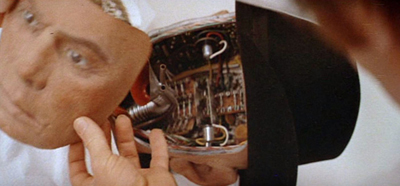

1973. Somewhere in Hollywood, Los Angeles. A beautiful young woman is laid on an operating table. A surgeon moves across to the table and removes a flesh plate from her abdomen area, exposing a swell of electronic wiring and circuitry. The film is Westworld. Superficially, we have a titillating, technological slant on the coitus shock us of both the de-feminised face in films like Queen Of Outer Space, She Demons, The Leech Woman, The Wasp Woman, Countess Dracula, She Freak and I Married A Werewolf, and the voluptuous but deadly mouth in films like Blood & Roses, Daughters Of Darkness, Vampyros Lesbos, The Velvet Vampire, The Vampire Lovers and Vampyres. That scene from Westworld more complexly works to clash a set of opposites (human/android, life/death, fertility/sterility, flesh/metal, body/machine, present/future, etc.) by engineering an erotic leveled at the body - its form, its texture, its image. Accordingly, Westworld's plot centres the body in terms of instigation (bodily pleasure sought by two men at the technological utopia), conflict (the mechanical body of the robot-gunslinger versus the human bodies of the two men) and resolution (the perfect body delivered by technology is morally condemned). While Westworld's deliberated themes are skin-deep, its body scenes carry a more pervading effect - from the carnage of humans dressed in utopian togas splayed and splattered across Grecian gardens through which the robot-gunslinger marches, to the pre-Terminator finale of a burnt and gutted mechanical corpse which refuses to cease functioning despite the obliteration of all its required mechanics.

Throughout the seventies, outer appearances were increasingly eroticized. In a way, the onslaught of Hammer/Amicus/AIP neo-gothic horror and the spread of European and American independent splatter in the early seventies constitute a pubescent period in the historical development of the body into its current contemporary form. From buxom lesbian vampires to close-up anatomical experiments, the body was blooming at the core of many films' concerns. Through the photographic medium, the body in horror was posed in a semi-pornographic light, reflecting our increasing engrossment with our body, showing us its potential for transformation and stimulation. As desires and obsessions were exacerbated in line with a consumer demand for new and novel product, the eroticism of the body was fractured into multiple pornographic modes - a fracturing whose widening gaps can be traced from The Vampire Lovers (70) to The Gore Gore Girls (71) to The Last House On The Left (72) to The Exorcist (73) to Flesh For Frankenstein (74) to The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (75) to Shivers (76) to Suspiria (77) to The Incredible Torture Show (aka Blood Sucking Freaks, 78) to Alien (79) and peaking with Friday The 13th (80).

Inner Presences

The pivotal horror in Westworld is our confrontation with a body of human form which is not human. This figure, of course, is classical. Consider those monsters whose human form belies inner presences - capable of transformation at will (vampires), waiting to be awakened (werewolves), totally void (zombies), or controlled by unworldly forces (possessed persons). What marks these figures as classical, in a sense, is the mystical nature of those inner presences. Conjured from a labyrinth of folklore and legend and re-ritualized on the screen, they mobilize our conception of our own selves as somehow mystical, somehow unattainable and unfathomable. Hermeneutics abound (the beast within us, our moral soul, our lustful drive, etc.) but the central fascination is with the in explainable - particularly of ourselves. The contemporary horror film focuses on a shift from this mode of identification to one based on disembodiment, where we are more fascinated with tactile presences than ethereal ones, and more interested in the body's exhibition of surfacial form than its disclosure of spiritual depths. Disembodiment, thus, signifies an absence of those inner presences. (Of course, some films don't just absent those inner presences - they massacre them!)

The body laid out in Westworld is transitional. It presents inner presence as a mass (and mess) of technology. That inner presence is reconstituted in table-scenes in films like Day Of The Dead (86), Re-Animator (85) and Return Of The Living Dead (85) as a mass (and mess) of biology. Forget the wonders of modern science and advanced technology - we are more overwhelmed by our very gizzards! The screen body in contemporary horror is thus a true place of physicality : a fountain of fascination, a bounty of bodily contact. If there is any mysticism left in the genre, it is that our own insides constitute a fifth dimension ; an unknowable world, an incomprehensible darkness. Could not most us admit that if suddenly we developed a gaping vaginal opening where our belly-button was, would we not explore it with our hand? And - like Max in Videodrome - if a gun was handy, would we not explore with it, in case we confronted something horrific in that black hole, that fifth dimension of physicality?

Gore

I have singled out the seventies here despite the emergence of gore movies in the mid sixties, because in gore movies, the body - as a whole ripe for fragmentation, as a slab fresh for dissection - is generally subordinate to the intensification of blood into gore. The most socially acceptable form of 'intense' screen violence is where fresh, bloody fluid signifies the immediate instant of dramatic action - we could term it a dramatic mode of 'humorality' in that the drama is humoral, i.e. coming from the blood. Screen-blood eventually thickened into gore, into a state beyond liquidification and the dramatic instant, into a realm of ugly viscosity and voyeuristic pondering. This intensification - both of violence and its substance - is central to gore movies, replacing the shiny veneer of red with unsightly patches, splatters and blobs of half-recognizable offal ; making visible and dwelling upon the unseen modus operandi of butchers, surgeons, morticians, biologists, coroners, slaughtermen, etc. The body, as such, is essentially the platter for the gore effect : witness the table-scene in Blood Feast (63, often cited as the first gore movie) where the woman's body literally is a platter of parts, cuts, spills and gapes. My point here is that there is a developmental split between sixties' gore and seventies' horror in terms of their preoccupation. It is only because the gore movie was rediscovered in the latter seventies as a text to be readdressed that the past 23 years appear to have congealed into a single progression of horror and violence.

Some examples

Corporeality

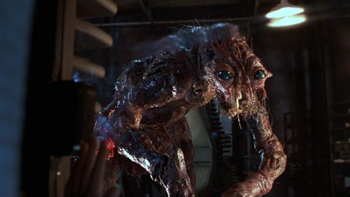

How far can too far go? The state of the art as I write has to be the scene in Day Of The Dead (86) [5] where a horde of zombies converge on a man caught on his back in a corridor. Most of them start ripping apart his abdominal region, exposing the rib cage and its insides which are plucked and picked, dripping and oozing, stretched in a moist explosion of viscosity and elasticity. Meanwhile other zombies concentrate on the head. Their fingers claw at the face, digging into his eyeballs for leverage as they slowly rip his head from his torso. Stringy, sinuous strands desperately cling onto the neck muscles, eventually snapping under tension. All throughout this, the man's mouth is open wide, tongue swollen in an exasperated scream, while his torso's arms flail, pathetically trying to fend off the barrage of limbs which methodically tear at their meat. Courtesy of George Romero's penchant for the visceral metaphor and Tom Savini's quest for the graphically impossible, this scene strangely echos the table-scene of Blood Feast as a gastronomical atrocity performed on the body. The difference, though, is that Day is not concerned with corpses, their desecration, emaciation and obliteration ; Day is concerned with - and gives new meaning to the term - corporeality.

Unlike the tragic figures of Lewton's zombies from the forties, Romero's zombies (staggering across his trilogy of films) are contemporary horrors : they embody our disembodiment. Like nerve motors whose only sense of reality is the immediate (in terms of space, time, memory and action), they reflect our potentiality as drained selves - bodies drained of the energy and impetus to figure or ponder our status, our nature, our existence. The zombie's sense of reality is defined by bodily contact, where the touch activates an acknowledgement of experiencing something, and where the flesh is the substance of both toucher and touched. (To put it in more conventional terms, the zombie "I" is dead flesh seeking a displaced "self" which is marked as such by being living flesh.) A new slant on the concept of 'corporeality' thus sums up a way of defining existence through the body. And this is the crux of our identification with the contemporary horror film : like those zombies, we use our bodies to understand.

Material Transgression

The above detailed scene from Day Of The Dead clusters many of our body concerns here. It is a scene which demonstrates well the relation between the body principles of Explosion and Expansion : the body is stretched to its limit, the body climaxes at that limit - and then the body overrides its limit. These limits, you see, are superfluous. They are there solely to define all manner of material transgression : stretching, severing, slashing, squashing. The body (incorporate) is the material of these transgressions. This, for example, is the epicentral horror in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre: the morbid fetishization of skin (from the decoration of lampshades to the encasing of sausage-meat) is the vehicle for horrifically flaunting material transgression ; portraying the remains of the body as the essential surface of its flesh, as physical evidence of its monstrous transgression. Thus, the skin is made as repulsive as the flesh is as repulsive as the organ is as repulsive as the body, etc. This is synechdochism in its most extreme form, in that, fantastically, body parts are just as capable of life, horror, eroticism and death as the body-whole. This is why The Evil Dead (82) is so streamlined : those possessed by demons can only be destroyed "by total bodily dismemberment" - the perfect solution to the totality of body horror.

Life and death? Find another genre for their philosophical reflection, because in the contemporary horror genre, life is merely the overture and first couple of movements hastily arriving at the finale, the operatic event of the act of death - an event which can be endlessly repeated (reportedly 19 times in the unedited version of Friday The 13th Part IV : The Final Chapter, 84 - and that doesn't include the numerous times Jason himself is butchered, only to miraculously keep living!) [6]. One finds it difficult to proclaim Day's headless victim as dead. His body remains living, still retains signs of living flesh - signs of which the zombies are fully aware. Of course we presume that this 'character' " dies, but - at the risk of extreme nihilism here - who cares? Just as the zombie's sensory perception functions through immediacy, so too does our identification with the death scene : only its eventfullness is of interest, the after-effects aren't of much consequence.

Absent Bodies

If Friday The 13th (the unexpected start of a series) is a peak in cataloging bodily fragmentation, and Day Of The Dead (the long-awaited end of a trilogy) a peak in stretching bodily limitation, they germinate from two films which helped state the contemporary horror genre as a sprawling plain of peaks : Alien (79) and The Thing (81). While the monsters of Friday and Day massacre the body's mystical inner presences contained in the symbolic flows of traditional genre conventions (intensifying the trend throughout the early seventies to consciously absent those inner presences) the monsters of Alien and Thing massacre inner presences by absenting their own bodies. This is clearly demonstrated in the exactness of the films' titles. The Alien-monster massacres by inhabiting the human body, using it initially as a living incubator, then feeding from it in order to shape its own body through a series of biological transmogrifications : the monster is 'alien' to the human body. The Thing-monster does likewise by simulating human form, hiding behind the human body and using it as bait for its sustenance : the monster is a 'thing' and not a human body. In both cases, the monster 'territorizes' the human body for terrifyingly pragmatic reasons (survival and growth) only to discard the claimed territory of the body in a spectacle of destruction, invoking the body principles of Expansion and Explosion.

Absent visibility of the monster is a strong convention in the history of the horror genre, deployed as a tease by not showing the monster fully (its full body, its total presence) until the climax of the film. Even apparently invisible monsters are rendered visible for the climax - through electrocution in The Thing (51), Forbidden Planet (54) and Five Million Miles To Earth (67) and by fire in The Prehistoric Sound (64). (Ironically, similar means force the monster into mobilization in Alien - flame throwers - and The Thing - electrical shock.) More oblique visualizations have been given to nonreciprocal monstrous figures through computer interfaces (Colossus : The Forbin Project, 70); electronic monitoring (The Andromeda Strain, 70); abstract video graphics (Demon Seed, 77); and ectoplasmic charges (The Entity, 82). (Note also, that the computer screen is used to mark the monster's presence in Alien and its constitution in The Thing.) In historical relation to these representational modes, monstrous entities have also taken primary-order material form as mist, slime, smog, rays, liquid, crystals, etc. Their existence is founded on their infection of, subjection to and projection on the human body, capable of transforming the flesh into stone, cellulose, vapour, ash, etc. (See The Green Slime, The Smog Monster, The Blob, The Incredible Shrinking Man, The Monolith Monsters, The 4-D Man, Virus, The Incredible Melting Man, etc.) All of these imaginings of monsters point to their objectification as a duality of representation and embodiment - how should it look and what should its form be? As such, generic invention lies as much in the absenting of their bodies as in their presentation.

Internal Bodies

Interacting between the symbolic mode of horror films (where inner presences are symbolized by human forms) and the iconic mode (where the human form is used as a framework for formal considerations of how the monstrous should be visualized) is a mode which internalizes both symbol and icon into the body. A prophetic movie here is City Of The Living Dead (82) where victims possessed by a satanic priest literally vomit their insides out. The literal and the visceral are compounded into a scene which replays body notions from Europe's Middle Ages (he possessed by the devil metamorphoses physically) and ancient China (he possessed by ghosts breaks out in sores). An even more precise image of how symbol and icon can be internalized into the body is the scene in The Fly (86) where a baboon is teleported and thereby molecularly reconstituted inside-out. The sight defies accurate description : the rough shape of the original creature is retained, but writhing as a mess of quivering organs. At this point in history, that scene alone stands as truly fantastic, virtually negating all other assumptions as to how the fantastic can be qualified in film today. The very thought of a still-living body totally turned inside-out is near unimaginable - but The Fly photographs it. Perhaps what makes that scene so fantastic is the degree to which it symbolizes such an impossibility through the body, rejecting recourses to metamorphosis and synergy, presenting us with the instant totality of its horror. (In a sense, we see what Max's hand felt in his vaginal wound in Videodrome.)

David Lynch has, like Cronenberg, exhibited an intense interest in the body, although not with the same consistency. Eraserhead and Shivers (both 76) both explore the body, but the former conveys its findings symbolically while the latter conveys them viscerally; both are motivated by a desire to discover the inner body, desiring to be transfixed by their discoveries (Eraserhead) and overwhelmed by them (Shivers). These relationships are intensified a decade later with Lynch's Blue Velvet and Cronenberg's The Fly (both 86) in the way that they represent the reflective conclusions of their journeys into the body. Cronenberg's inside-out baboon tells us what he finds inside us : our organs, total in their presence. Physiognomically, our outsides reveal our insides which reveal our outsides, ad nauseam. (As we shall find out later, The Fly then works the body according to this premise.) Lynch's discoveries touch on the repulsive, too, but not without retaining an aura of mystery.

In Blue Velvet, like Eraserhead, the body is transformed into an alien landscape whose unsolved mysteries instigate the quest of our journey, and as the human form undergoes a reverse-anthropomorphism, we penetrate its walls, cavities, chambers. While both films are rich in symbolism (whose self-conscious presentation seems deliberate), those quests somehow don't feel psychological in their orientation. It's as though one is recognizing those mysterious, inner psychological impulses not as solutions or explicatives (in the psycho-analytic manner) but as their own symbols, as icons. One can interpret a mansion full of wombs, sperm, penes, vaginae in Eraserhead, [7] but one should also consider the 'writing degree' of those signs. Blue Velvet in a sense rewrites those signs more clearly as visual icons whose phenomenological presence (photographically, cinematically, semiologically and symbolically) is employed as textual atmosphere to the narrative : from the severed ear found on the ground to the camera's penetration into the darkness of its inner world; from the throbbing, dizzying drape of blue velvet behind the credits to its place in the grotesque display of a basic Freudian scenario; from the igniting of a candle - to create the feel of darkness - to the ignition of every possible dark feeling imaginable. Blue Velvet transfixes through its complicated and confusing overlays of fabrics, surfaces and textures both on top of and within the body. This type of symbolism indicates what could be termed a 'textual syllepsism', where symbols and icons converge on one another. The Fly uncovers them as more organs; Blue Velvet discovers them as more darkness. Like much contemporary horror, these two films realize that the most we can ever encounter inside our bodies is more bodies [8].

Flesh-Bodies

The Creeping Flesh (72) - like Westworld - is both transitional and seminal. And like Alien and The Thing, its title is exact : the Oxford dictionary notes "horror" as derived from "horripilation", where a feeling of dread causes the physical reaction of one's skin tightening and forcing the hairs to stand on end - otherwise known as "the creeping of the flesh". (Ergo, it would appear that horror is physical.) As a transition in the development of the contemporary horror film, The Creeping Flesh projects the notion of horripilation onto a monstrous body. A giant, pre-neanderthal skeleton is found in New Guinea ; inexplicably, its material substance still withholds a life force, so that when water touches the bone tissue, it mutates into dripping, yellow flesh. This subtext makes an otherwise pedestrian neo-gothic film of interest here when one notices that : (a) the hand (which first develops and is severed for analysis) bears an uncanny resemblance to the jaundiced 'face-hugger' of Alien's secondary organic phase plus the initial flesh-mutation of the remake of The Blob (87); and (b) the bilious tissue prefigures the suppuration trend in 'melt, crack & splat' movies like The Devil's Rain (75), The Incredible Melting Man (77), Phantasm (79), Demons (85) and Street Trash (87). The Creeping Flesh, then, features a body of flesh, a flesh-body : a vehicle for articulating how tactility itself can be made monstrous, how touching can be both fearful and pleasurable. The vile and globular exo-skeleton in Flesh eroticizes the touch (our desire to feel the liquescence) and de-eroticizes the flesh (our repulsion in recognizing our body in that putrid state).

This notion of a flesh-body exercises the duality its terminology suggests - a duality that can be made apparent by comparing The Creeping Flesh (its accent on 'flesh') with The Hand (81, its accent on the 'body'). Both films site the severed hand as a body of power whose form symbolizes the motor drive (literally) that can excite sexual desire - the hand compelled to touch. Consider this in relation to the erotic symbolism of the severed, dislocated or displaced hand in films as varied as Un Chien Andalou (28), Mad Love (35), The Beast With Five Fingers (46), The 5000 Fingers Of Dr.T (53), Dr. No (63) and Blood From The Mummy's Tomb (72) where dread and awe are instilled through either the manic 'motorized' power that replaces the once-connected hand (metal contraptions, leather gloves, etc.) or the hand's ability to move of its own accord, just as one's own sexual drive and motor impulses can each appear to have a 'life of its own'. The severed hand - as both a subject and object of horror - embodies the titillating potential to touch that which we cannot consciously bring ourselves to touch ; its nerve endings are not only severed from the brain, but also from the psyche. This of course is all fairly evident. The interesting relationship between The Creeping Flesh and The Hand is not what is either latent or manifest - but what is represented and how it is depicted.

The Hand plays out its psycho-analytic workings as a scripted framework, right down to having Michael Caine (playing a comic-strip artist who looses his right hand in the midst of a domestic squabble with his wife) dismisses his consequent neurosis as a "penis complex". The film's focus is not Caine but his hand (the hand of the film's title) and how it embodies everything that results from its severance. This is an important point, because in its focus on the hand as a flesh-body The Hand is concerned not with how Caine (as a psychologically motivated character) deals with his trauma, but with how Caine (as a textual seme) discovers that it is his severed hand itself that contains that trauma. Caine thus has to first chase, catch, battle and confront the hand before he can start dealing with the trauma ; his hand (now displaced as "the hand") becomes a very clear object of desire, an overwhelming manifestation of all that repulses and excites in the touch : a flesh-body. While The Creeping Flesh focuses the trauma of the touch onto a monstrous 'other' (but still retaining enough signs of 'our-selves' to repulse and excite us) The Hand characterizes 'us' in Caine. His otherness is depicted as a monster precisely because it has momentarily achieved the analyst's dream : to become separate.

The doublings and multiplications continue in The Evil Dead. Consider the image of Caine's two hands (one a mechanical instrument encased in a black leather glove, the other his organic left hand) struggling to stop his severed right hand choking him. This is given an over-the-top treatment in The Evil Dead where a possessed girl is stabbed in the hand with a mystical knife - she then chews off her own hand and proceeds to stab Bruce Campbell with her severed hand containing the impaled knife. Both scenes project a vertigo of hand placement and displacement where it visually doesn't make sense as to what is happening with all the hands. Just as the severed hand starts to symbolize psychological separation of the self, that separation is intensified and escalated like the breeding phallic brooms of The Sorcerer's Apprentice, negating or obscuring any single picture of the self that consumes such hysterical imagery. (A quick foot note : in The Evil Dead II, 87, Bruce Campbell returns to battle more possessed friends, and this time to save himself becoming possessed he chops off his own hand!)

Pornographs

Our trail from The Creeping Flesh to The Hand traces the impressions of surrealism upon this particular terrain of body images. The Hand's black and white scenes (which narratively describe both the hand's point-of-view and Caine's sexual suppression through blackouts) strongly evoke the cinematography of Eraserhead, not just stylistically (Flemish-industrial-surrealism!?) but also texturally. The Hand also features the memorable image of a severed hand moving slightly in light scrub, covered with assorted bugs and insects. This image of course reappears - as a severed ear - in another Lynch film, Blue Velvet. Neither Blue Velvet nor The Hand, though, are playing out surrealist effect here ('quoting' Un Chien Andalou's hand-of-ants or Repulsion's dead-hare-with-flies) because the reason, cause and nature of such an effect is no longer some weird, mysterious, arty gesture confined to a surrealist manifesto enshrined by the museum. This is so much the case that a horror comedy like Waxwork (86) features a scene where a kid falls into the dimensional scenario of a waxwork depicting a scene from what is a loose quote of Romero's black & white zombie movie Night Of The Living Dead (68). Everything turns black & white and the kid is grabbed by a zombie. He hacks the zombie's hand off and runs away with the hand still attached to his ankle. He stops, grabs the hand, and then the hand grabs his hand. This gag continues for a while - hands grabbing hands - until the kid looks up at a spiked cemetery gate. He jumps up as if to climb out of the cemetery - but instead slams the hand onto one of the spikes. Just as this scene is not a reference to Rod Steiger slamming his hand on an invoice spike in The Pawnbroker (65), Blue Velvet and The Hand do not academically induce Surrealism. Whilst the Surrealists were attracted to the auratic quality and erotic power of the photograph, films three to four decades later evidence a more sophisticated play with the cinema's photographic lexicon of sexual effect through bodily depiction. In reference to our concerns here : surreality has been overtaken in the act of cognition as 'corporeality', while the generality of a photograph has been replaced by the specificity of what can be termed a 'pornograph'. Body images and scenes in the contemporary horror film are less symbols of sex and more signs of sex.

Pornographs are those signs. As specific modes of bodily depiction that signify and/or simulate conventional pornographic codes, they can be divided into two types : the first figured through the camera, the second through the photograph. To cover the first type, we have to recount our steps back through The Hand to The Evil Dead (82). In the former, as Michael Caine finally traps his hand in a barn, an overhead tracking shot follows his cautious entry into the barn, complete with rafters slowly passing in front of our point-of-view of the top of Caine's head. Compare this shot with an identical set-up accentuating the eerie pause prior to the grand guignol finale of Bruce Campbell's battle with his possessed friends in the shack in The Evil Dead. The slow seductive movement makes all objects (rafters, walls, etc.) within the frame cruise past the only fixed object - Caine/Campbell, who thereby function as objects of not only our identification but also our focus. Like the giddiness of the Big Dipper carnival ride, it is not the focused (ie. the head in front of us) that unsettles the stomach, but rather the whizzing and whirling visual abstraction that assaults the cornea, affecting our balance with its unfocused movement.

This connection of camerawork shuttles us back to The Shining (80) which was the first film to exploit the Steadicam camera's designed ability to displace point-of-views more seductively than ever before, enabling our complex identification to move with the narrative's cinematic construction, as opposed to being fixed to a scene or arrested by an image (via the semantic organization of symbols and motifs). In The Shining's maze of tracks, flows and rides the erotic of movement with equilibrium (effected by the Steadicam's fluid balance) conflates the voyeuristic experience of moving within the narrative - not freeing us from identification, but snaring our involvement with deadly precision in a sort of 'suture-on-the-run' where it is as if we can almost feel the sensation of being sewn into the text. Interestingly, it took other films to fully exploit (and in many cases 'fake') the Steadicam and the similarly principled Louma crane in this respect, the first clear wave happening in 1982 : The Evil Dead (with its 'forest rape' scene and the end rush through the house up to Campbell's face) ; Amityville II : The Possession (with its floor-to-ceiling-back-to-floor shot of the possessed teenager) ; and Tenebrae (with its multiple reconnaissances and surveillances that lead up to the gruesome slashings). In all these examples, the camera does something it didn't do in The Shining - it covers the body ; obsessively lingering, hovering and floating above its surface, caressing its outline and mapping its presence. Thus we reach a definition of this proposed first type of 'pornograph' : a pornographic encoding of the body and its form through the mechanics and dynamics of camerawork, focusing and shifting a frame for the body in a mix of balance and unbalance [9].

The Creeping Flesh and The Hand - in their capacity for instancing flesh-bodies - are examples of a second type of 'pornograph' whose definition would be : a pornographic encoding of the body and its flesh through the chemical effects of the photographic process, accenting and highlighting selected visual elements in a mix of eroticism and de-eroticism. The symbolic and semiotic performance of the severed hand in those two films shapes their flesh-bodies, while their depiction - their graphic rendering - of the hands' flesh (from dripping yellow to pasty grey, etc.) hint at the innate abstraction of flesh, that its physical surfaces are eternal displacements of other identical surfaces of other possible body realms (from pus to gangrene, etc.). Conversely, one can read hard-core pornographic imagery as horrific (i.e. alien, unworldly, non-bodily) in its reconstitution of the body and its flesh, where organ, muscle, tissue and secretion convey their effect through a type of 'semiotic abstraction' : the real photographed as abstract to signify the real. The photography here accents material surfaces more than it portrays recognizable parts and wholes. Bodies (their insides and their outsides) in contemporary horror films exploit and are exploited by this inherent quality of the photographic medium, in the act of photography - in the transposed act of 'pornography'.

Indeed, rather than condemning the horror genre as pornographic, [10] one should perhaps be considering whether it is possible to not invoke an erotic vacillation in the photographic (and hence cinematographic) act. The notion of a 'pornograph' can in this light correlate other 'graphs' - photo/cinema/phono/auto/etc. - in its mapping, coordinating and voluming of the body, just as the 'graph' does with still and moving images, sounds, signatures, etc. Even though I implicate myself in dismissing the patriarchal appropriation of language by disregarding the mid-19th century English derivation of "porno" from the Greek meaning harlot and prostitute, I still wish to suggest that 'pornograph' could - at least - connote a mapping of the body. I do not propose the body as some physical, neutral universal, but rather intend to demonstrate how any 'graph' deals with a 'body' of some sort, and that, subsequently, pornography is inherent (or at least predominant) in many forms of pictorial and material documentation.

By following through this proposition on pornography, we can link up some notions and points raised earlier in this article. Charles Atlas' objectification of his own body, for example, constitutes a pornographic act, with himself as pornographer and his body as pornograph. Furthermore, self-objectification brings us back or around to a notion of auto-eroticism : using one's body to arouse one's body like a stimulatory moebius strip. This is both the profundity underscoring the casual concept of "look good - feel good - be good", and a fundamental social drive in the life-style and leisure-activity of body-building for both sexes. While the muscular body in its hard-on state [11] can be repulsive and horrifying (through its physical eruption of desire and eroticism across the body's frame) its quest for 'beauty' (a formal and ritual consideration in the body-building arena) reflects the bodily gratification which the body can grant itself, as a place of physicality, a central zone for maintaining and servicing desire. The sweaty pulsations in Flashdance and the tense throbbings of Rambo plug into this notion of pornography - teetering between orgasmic beauty and physical repulsion ; moving with the body principles unleashed in the contemporary horror film, exercised in the body-building phenomenon, and stroked in hard-core pornography.

Metallic Erections

Aliens (86) literally transforms its body concerns into a plurality of effects, dealing with the multiplication not only of its featured monster but also of the monstrosities birthed by the cinematic text [12]. Aliens talks to Alien, reflecting, restyling, reforming the intricate mise-en-scene of the original, shaping it into a secondary narrative that attaches itself to and grows out from the scenery of the original. We now learn in their textual dialogue that the underside of those 'face-huggers' is a vaginal vacuum, a pudendum turned inside-out and ready to suck the life out of you ; that Ripley's taut, drained hands - yellow-tanned and skeletal - resembles the face-hugger's cadaverous digitals ; that the womb is revealed here not as a technological clinic but as a real, living architecture ; and that Ripley's own body has been 'retextured' as a lesbian erotic, a genuine lesbian erotica of sweaty, non-feminine bodies of strength. Aliens may be summed up as James Cameron's 'Rambofication' of Ridley Scott's pictorial detail, but it also violently tugs at Alien's visual subtext, stretching it, squashing it, fraying it, pulping it.

Perpendicular to this self-interrogation, Aliens experiments with the Expansion principle in contrast to Day Of The Dead's laboratorial scenes of Explosion. (It should be noted here that the only real scenes of Explosion in Aliens involve the android whose human form is torn in half, but whose bionic design continues to function.) Aliens' bodies (human and alien) are expanded in many ways, and these ways can be grouped together by their experimental slant on Expansion: erection. These erections can be of flesh or metal, and of the penis or the clitoris [13]. The 'queen bitch' alien is a grotesque exaggeration of the drone/soldier aliens in her size, stance and overall dimensional presence. Her body is her world, expanded into a maze of alien tissue, into which the humans - as anti-bodies - enter, recalling the horrific erotic of Raquel Welch swimming in our plasma stream in Fantastic Voyage. (Remembering our identification with inner presences, the incubating labyrinth is our own 'fantastic voyage', our fifth dimension visited upon us from within.) While the drone/soldier bodies do not differ all that much in design from the original film, the human crew certainly do. Backing up the lesbian 'retexturing' of Ripley and her 'macho-femmandos' is their weaponry - sci-fi visions of the humongous blast-chargers of Norris, Stallone and Schwarzenegger. Slung low on their hips, they protrude like hysterical phalli, sweeping across our eyeballs as the camera tracks around their rigorous yet balletic reconnaissance movements. These grey cocks, these metallic erections do not, however, erupt from the body ; like all those Stallone/Norris/Schwarzenegger gun poses, they are material expansions of the body, where metal is the material substance of their erection, their transgression from flesh to metal. It is thus the act of Expansion which gives the impression of their fusion, even though the metal is not fused with the flesh [14].

Videodrome's (81) 'hand-gun' is a fusion and not an expansion (we shall discuss fusions later), as is its erogenous television screen and organic video cassette. Furthermore, its Explosions - smashing screens, splitting bodies - create black holes, which are possible entrances into our unknowable bodies (a central thematic to the film). But more relevant here is the relation between Videodrome and Alien, based on their production design and art direction which constructs a mise-en-scene that polarizes flesh and metal. Technically, Alien's architectural design relates to Videodrome's industrial design, locating the former's chambers, corridors, tunnels and shafts (and the monster's ability to camouflage itself) with the latter's technological components (and their transformation from hardware to 'software'). The notion of metallic erection - as a principle of Expansion - arises from this discursive networking between Alien and Videodrome.

The end battle of Aliens alludes to everything from the W.W.F.'s 'hyper-wrestling' (they call it "rock'n'wrestling") to the latter Toho monster movies which were spectacles of 'gargantuan-wrestling' (the only things missing from Godzilla Vs. Megalon are the turnbuckles). In the left corner, the new Mother who wrenched the title from the super-computer in the original film. In the right corner, the contending Mother, a fertile and heady mix of maternal and libidinal desire, desperate to resolve the two through victory and supremacy. What ensues is an incredible fight to the death between alien Expansion and human Expansion ; between the Alien's towering inferno of acidic proto plasma, crustaceous muscle and metallic teeth, and Ripley's agile encasement of nerve and verve in a mega-exo-skeleton operated by (remembering the previously listed special effects for Expansion) hydraulics, pumps and valves. Note, also, how erect they are in their battle - the alien reeling back and propped up on her interlocking limbs, and Ripley clanking around like a bionic automaton ; both stiffened and hardened by their metal embattlement. (And let's not forget what's in a name : Ripley as in ripple as in muscle.)

Ripley excites a strong body-desire here : not simply that of building up one's body like Charles Atlas, but of utilizing technology (the mega-exo-skeletons) to instantly change one's bodily dimensions and become a bionic machine without recourse to medical operation. (This is perhaps where our key identification with The Terminator, 85, lies - especially considering the scene where the terminator performs a techno-medico operation upon himself.) Technology can thus allow us to create and then realize a new bodily potential at will. The proliferation of mega-men and machine-men is extremely relevant here : see the films/cartoons/toys of Machine Men, Transformers, Rock Lords, Ultra Men, Robotechs, Masters Of The Universe, Thundercats, Voltrons, Centurions, W.W.F. Wrestling Dolls, etc. and note the semiotics of their techno-design and the semantics of their techno-jargon [15]. This general 'bionic desire' is thus a key motivator of metallic erection.

Fusion

Like the third and final teleportation which results in the 'Brundle-Fly-Pod' in The Fly (86), horror/porn/body-building form a, so to say, molecularly fused triad. The human form (to call upon the overload of neologisms, metaphors and general linguistic recontextualization in this article!) as a flesh-body, as a phenomenal agent, and as a place of physicality is both whole and parts in that fusion, and thus the central element in the contemporary horror film's 'textual syllepsism'. That bicep is an image from Fangoria, Hustler and Muscle & Fitness ; this video cassette is an animated montage of their pages ; your identification is an erotic vacillation, hedonistically incapable of or unwilling to fix the vacillation, to 'understand' your self or your body.

The Fly marks a peak not just of this fusion, but of a dialectic for that fusion. Extending the ambiguity of the body which both arouses and repulses in previous Cronenberg films Shivers (76), Rabid (77) and Videodrome (81), The Fly displays an adroit and dexterous control of erotic vacillation. This is executed at varying thematic and narrative levels : from Goldblum's tragic central character (devouring junk food with his sperm-like digestive acids) to Goldblum and Davis' decaying romance (their hugging as a poetic symphitism of bodies alien to one another) to the mise-en-scene for their relationship (her cutting the first fly hairs on his back while he scoops out ice cream) to our contemplation beyond the film's ending (as much as she loves him - is she really going to conceive the Brundle-Fly larva!?). The story invokes a whirling mix of textual fragments : the mourning of a close friend, the legend of Frankenstein's monster, the pathos of the mad scientist, the intensity of true love, the fear of bodily control, the thrill of exploring new dimensions, the quest for knowledge, the inevitability of scientific progress, the enigma of cancer, the role of chance - what doesn't this film take on? What doesn't this film fuse?

In terms of generic development, we could be witnessing a heady split here - between Day Of The Dead with its syncopated, polyphonic play with Expansion and Explosion (combining their effects), Blue Velvet and its arrhythmic, subharmonic play with those same bodily principles (inverting their effects), and The Fly with its synchronized, monophonic play (fusing their effects). Where Day expands by exploding and explodes by expanding the body and its parts, and Blue Velvet inverts the processes of those effects, The Fly bides its time with them : delaying, halting, freezing, detaining, waylaying, withholding the eventfulness of the expected operatic acts of violence. The Fly's scenes of body horror are in fact not temporal ; they do not happen- they appear. Steady in their statement, static in their unfolding, total in their fusion : from Brundle calmly chewing off his nails to the accepted growth of his "museum of natural history" ; from the disconcerting pimples on his face to the consuming lumps all over his body ; from the sharp computer image of his fused cells to the steaming compressed sculpture of his final, re-incorporated body.

Delineating all the space between the sympathy of characters and the symbiosis of molecules, The Fly is a story of intense fusion. No wonder it ends with an almighty bang, shattering and tearing asunder the incessant binding, congealing, sealing and hardening of every narrative level, every textual element, every poetic figure in its telling. Like a glittering diamond created from incredible pressure applied to black coal, The Fly releases itself in its suicidal finale of bright, blasting light - replacing the black hole which swallows up the boom of Max blowing out his brains in Videodrome.

One wonders where we might go from here. The world of the unworldly seems equally divided - between Romero's plateau of infinite eventeration, Lynch's subterrain of feculent introspection, and Cronenberg's hinterland of visceral unification. Their territories of terrorization are encapsulated in a roaming and roving world, inhabited by bodies beautiful and horrible. Some of them theirs - most of them ours.

Notes

1 All information on Atlas here is obtained from The Life & Times Of Charles Atlas by George Butler and Charles Gaines, 1982.

2 Pop Music Where? Part 1 : Semiology In The Flesh - Virgin Press No.19 Nov.1982.

3 Tales Of Terror - Cinema Papers No.49 Dec.1984.

4 All Horror Movies Are Sick : True Or False? in Cinema Papers No.62, March 1987 for more on the relation between humour/comedy and horror/terror. See Vile Bodies And Bad Medicine by Pete Boss, Screen Vol.27 No.1 Jan-Feb 1986 for an account of how the medical can horrify.

5 George Romero's Day Of The Dead (86) was "refused classification" (i.e. banned) for a theatrical release in Australia in November 1986. By December, though, every key gore scene from this banned film turned up in a R-rated video release Scream Greats No.1 : Tom Savini, a projected documentary series produced by Fangoria magazine.

6. Although it is not the province of this article to note the function of the body throughout the whole history of the horror genre (and such a project still needs to be undertaken), it is worth pointing out a strange connection between the action and horror genres. Consider the action film as defined in the early seventies - para-military, absurdly-macho, oscillating between the urban jungle and the urbanized jungle, dwelling on the mechanisms of crime, glorifying violence, etc. Whilst generic specifics will continually change in this sub-genre, one visual figure always stands : the explosion. The great, cathartic finale where anything and everything is dynamited (like a cyclical closure from the atom bomb to the Bog Bang Theory). This scene (classically defined, as it were, in a film like The Bridge On The River Kwai, 57, where the central object is there to be destroyed) soon gave way to an illogical sequence of explosions, 'triggered' purely for effect. Through orgiastic ellipsism, any single explosion then became a real-time and screen-time fracture, where the one event was shown from a multiple of angles. These kind of action films could be typed "Explosion Flicks" in the way that the horror genre has its "Slasher Flicks" : both replay a figure purely for effect, and in doing so render the conventional narrative form not simply as ruptured, but as a thin yet solid sediment of ruptures clasping all those explosions and slashes. Without detailing the symbolic history of the explosion (consider the rich though conventional symbolism of the burning house in many gothic horror films) it can be indicated that the erotic of the Explosion principle in the contemporary horror film had previously worked symbolically in the action film.

7. For an informative reading of Eraserhead in this psychological mode see K. George Godwin's article in Film Quarterly, Vol.XXXIX, No.1, Fall 1985. In terms of auteurist analysis, though, Blue Velvet now prompts us to reconsider the 'symbolism' of Eraserhead. A close analysis thus needs to be performed on Blue Velvet in order to reveal the 'second degree' nature of its symbolism.

8. Historically, this symbolic and iconic flux between the body form and the internal body is well demonstrated in the Creature trilogy, where each installment reveals that inside the Creature lives a human form. In Revenge Of The Creature, for example, his scaly covering is burnt off to reveal a metamorphosing flesh. (The Creature From The Black Lagoon, 54 ; Revenge Of The Creature, 55 ; & The Creature Walks Among Us, 56.)

9. As the networking team of Steve Raimi, Robert Tappert, Ethan Cohen and Joel Cohen continue to refine a truly contemporary cinematic dialectic based on compression (in The Evil Dead, 82, Blood Simple, 85, Crime Wave, 86, and Raising Arizona, 87) its worth mentioning some production details of The Evil Dead II, 87 : Raimi (with the aide of Verne Hyde in charge of mechanical FX) has apparently developed some truly hysterical camera contraptions that exaggerate the standard effects of the Steadicam - one of which he has named the "Torso-Cam". If that's not evidence of a 'pornograph' I don't what is.

10. The views of The New York Times' film critic Janet Maslin on the contemporary horror film were syndicated in The San Francisco Examiner-Chronicle as "The Horror Genre Turns To 'Violent Pornography'" and sub-headed as "a critic's disgust over exploitative movies". (Since then - late 1982 - Maslin has been the occasional butt of Joe Bob Briggs' comments on East Coast liberalism.)

11. Ted Colless and David Kelly quote Alphonso Lingis' description of the muscle-pumping body as "having a hard on everywhere" in their The Lost World, Art & Text No.3 Spring 1981. A brief flick through any body-building magazine will demonstrate this effect. For more on the spectacles of body-building and stripping, see my Pop Music Where? Part 2 : Fleshy Semiotics, Virgin Press No.21 Dec 1982 ; Demolition Man by Ted Colless & Paul Foss, and The Strip Laid Bare : Unevenly by Mick Carter (both in Art & Text No.10, Winter 1983).

12. My account of Aliens here is an indirect response to Barbara Creed's Horror & The Monstrous-Feminine - An Imaginary Abjection, Screen Vol.27 No.1 Jan/Feb 1986, which posits a fascinating reading of Alien, but only when she addresses the film. (Unfortunately, she seems more concerned with applying Kristeva than reading Alien.) Her reading, however, should be taken in conjunction with the invaluable Alien Movie Novel, 1979, edited by Richard J. Anobile, which - through its photographic layout - more clearly demonstrates many of the semiotic and symbolic flows she addresses. (See also Aliens : The Official Movie Book, 1986, edited by David McDonnell & Carr D'Angelo for the 'inside' story of Aliens' - the sequel - creation and production.) Creed's analytic method is suitable for those who wish to understand their/the body. The analytic method of this article is suitable for those who wish to know "not how we might understand our bodies, but how we might use our bodies to understand."

13. See (only if you really want to) Big Clit Magazine : "Watch' em get hard and erect like a big cock!" There is a porn mag for every possible body part and function imaginable. The problematic mystery is who reads them?

14. Consider the scene in Commando (85) where Schwarzenegger - the man 'pushed too far' - reverts to means he had forsaken, i.e. killing people. In preparation for the execution of those means, he covers his body in an incredible array of armature, portraying him as a physical image of armipotence. Dressed in camouflage gear and make-up, his costume works more to camouflage the flesh with metal, rather than the soldier with his surroundings. He thus tramps off : a monstrous conglomeration of muscle and metal, a fusion of 'arms', thickened with murderous desire. This scene of 'dressing-up' and 'thickening' the body occurs in most modern action-military-revenge films.

15. See especially the 1987 range of Masters Of The Universe dolls which mechanically perform (in plastic) the most incredible transformations. More importantly, note the use of these toys : they are designed for kids to pull them apart, reshape them, transform them. Kids are playing with the nature of the contemporary body here, by freely experiencing the body as open-ended set of constitutions : from flesh to metal; from body to machine; from image to object; from inside to outside; from transformation to restoration. The very design and pleasure of these toys is that they should not be fixed in terms of form and function. Accordingly, many kids - and adults, I hope - are more and more reading culture as unconstituted; as a continually moving transference between factors and elements which we had previously interpreted (or rather, used) as fixtures.

End Note

The wild notions, points and examples in this article may not be all that applicable elsewhere. They have been inspired by certain films (mentioned) and have been bashed together in the way one would play with a Meccano set : connections are made across, underneath and through sections, partitions and layers, but their overall interelationship as a fixture or construct is essentially of a stand-or-fall nature. My writing, though, (as a continuation of my articles on the contemporary horror film) is impelled by the idea that some of the films mentioned here - for good or for bad - can be more recognized as illustrative of sublime cinematic invention.

Text © Philip Brophy. Images © respective copyright holders.